Go to Tang Poems (volume 2)

Tang Poems

(volume 1)

Annotated with Chinese historical references and explanations.

25 top Tang poems of the Tang Dynasty by 10 poets

|

Authors: Marie L. Sun and Alex K. Sun

(Mother and Son)

This eBook is published by

Amazon.com

(美国亚马逊公司/美亚)

and sold by all Amazon stores around the world (please refer to Home page) but not by Amazon.cn yet.

Tips:

For beginners:

For beginners:

Here is the easiest way to purchase your very first kindle book - paid or free:

You don't need any Amazon Kindle Reader device to purchase any book thru Amazon.com.

You may use your PC, Laptop, Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android phone or other mobil phone etc. to purchase it and read it with Amazon Cloud Reader  (it's a free software) thru your PC, Laptop, Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android phone or other mobil phone etc.

(it's a free software) thru your PC, Laptop, Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android phone or other mobil phone etc.

It also provides special instructions for people located in China or certain other foreign countries.

Calligraphy images referred by the book

may be freely copied from this website

for educational or noncommercial positive purposes (i.e., no gambling or pornography, etc.) with an attributional reference to

"Marie Sun and Alex Sun or at MarieSun.com" ; other uses require explicit, written authorization by Marie Sun.

Calligraphy images referred by the book

may be freely copied from this website

for educational or noncommercial positive purposes (i.e., no gambling or pornography, etc.) with an attributional reference to

"Marie Sun and Alex Sun or at MarieSun.com" ; other uses require explicit, written authorization by Marie Sun.

Preface

This book is dedicated to the memory of Marie's dear parents, Mr. Tieqing Luo (羅鐵青先生) and Ms. Wu Ma (馬勿女士), who inspired Marie's early interest in and appreciation of Tang poetry and Chinese calligraphy.

The book is structured differently from any other book on Tang poetry. Rather than simply providing a translated poem in isolation, it provides in-depth historical and cultural background information surrounding the poem, accompanied by multimedia links to maps, images, and/or videos scripts, including recitations in Mandarin for each of the 25 poems. In this way, the reader can more fully understand and appreciate all the nuances of the poem in its Chinese cultural context.

In particular, this book provides information regarding

Tang era social structures, key turning points relating to the rise and fall of the Tang Dynasty, and the political machinations of imperial court life -- all of which informed the narrative of Tang poetry.

Of particular note is one singularly key figure of the Tang era -- Emperor Tang Ming Huang, who promoted poetry during his reign and led to its Golden age in Chinese history.

In keeping with the old adage that "a picture is worth a thousand words," image/video links are provided from time to time to accompany a poem to help put it in context:

The Great Wall thru Google,

Section of Silk Road in the desert thru Yahoo,

Hanging coffin thru Baidu, and

Installing coffin on towering cliff face thru YouTube, etc.

After more than 1,000 years of weather and war, the structures above may no longer retain all of their original glory, yet they still hint at the grandeur of a bygone golden era.

The beauty of Tang poems is that they can evoke precise visions in an efficient conservation of words, forged into a euphonious stream of rhyme and cadence. These poems represent, and are witness to, archetypical human emotions and pondering reflecting the glory, passion, and tears of a unique era in Chinese history.

If you are not familiar with the history of the Tang, I encourage you to first read

Chapter 2 - The Historical Path that Led Tang to Glory or

at MarieSun.com Chapter 2 - The Historical Path ... before continuing with the rest of the book. The mood and subject matter of Tang poetry tended to reflect the relative strength and status of the state, such that a knowledge of the political history of the dynasty will give you more insight into the poetry.

* * *

When translating Tang poems into English, the poems' forms, cadences,

and rhyming schemes are naturally difficult to replicate precisely.

This book attempts to retain the poems' original charm, flavor, and

soul, while adhering as closely as possible to those original forms,

cadence, and rhyming schemes.

The essentialist, ambiguous,

and rhythmic spirit of Chinese poems is often lost in flourished occidental

translations trying to explain and make sense of too much. Chinese poems are often purposely designed to be ambiguous or open to interpretation. For example,

in most cases, there is no overt subject in Chinese poems, though the

first person viewpoint is usually understood. Thus, the subject "I" is

often inserted as the assumed viewpoint in occidental translations.

This book attempts to avoid such assumptions except in the most obvious cases.

I hope you will find pleasure and enjoyment in perusing this book, and that you will engage in interpreting the poems you come across in your own way and share them with your friends.

* * *

The co-author, Alex Sun, was invited by his dear grandparents, Mr. Teiqing Luo and Ms. Wu Ma, to study Chinese in Taipei, Taiwan at age 12. Alex's natural interest in learning different languages and cultures, along with his immersion for 2 years in Chinese-speaking communities (studying another year at Beijing University in China), proved an immeasurable help in producing this book.

An enormous thanks also goes out to Scott Shay, a computer expert and linguist who has authored several college textbook from

www.amazon.com/Scott-Shay/e/B002BLS206.

With his help, we have been able to publish our first eBook. Also thanks to Benjie Sun for his editorial help and Chung-Li Sun for his spiritual support.

Copyright

All rights reserved. The scanning, uploading, and/or distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the authors is illegal and strictly forbidden.

How the Information in this Book Is Organized

This book is divided into several chapters, with the first containing the 25 chosen Tang poems organized by poets. Subsequent chapters provided

further general historical and background information.

In Chapter 1, the following information is provided for each poem:

(1). A brief biography of each poet, except for Li Bai and Du Fu, who are described in more detail, due to their seminal influence in the East Asian poetry world (in addition, there is an entire chapter devoted to Tang Ming Huang, the Emperor patron of poetry).

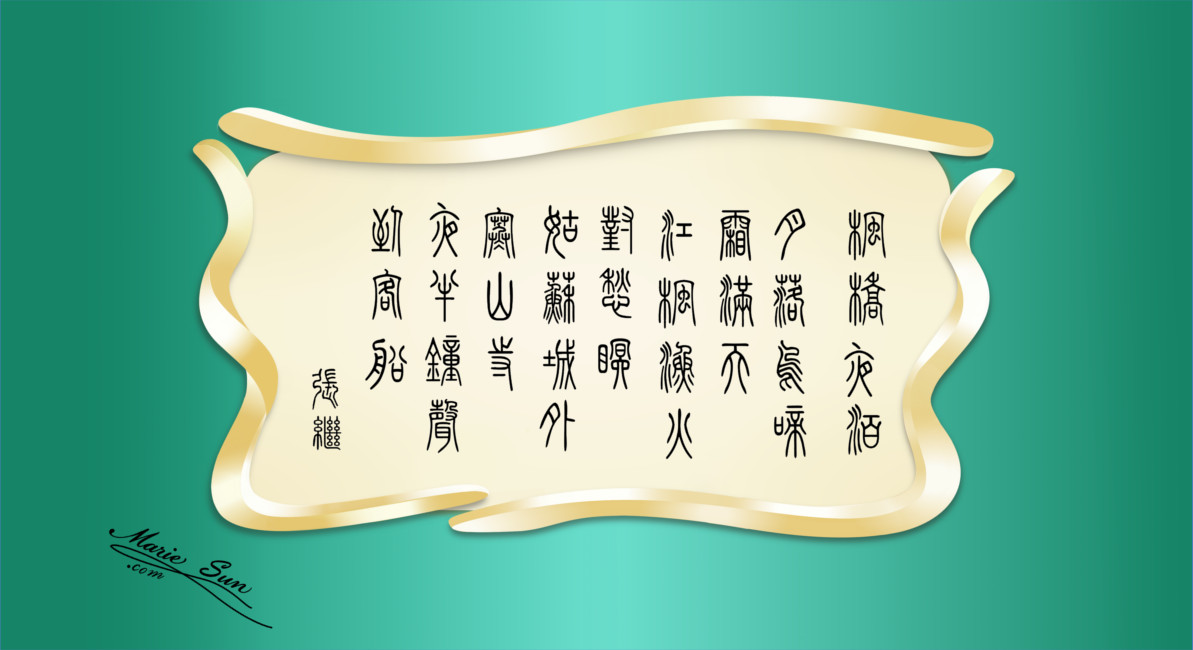

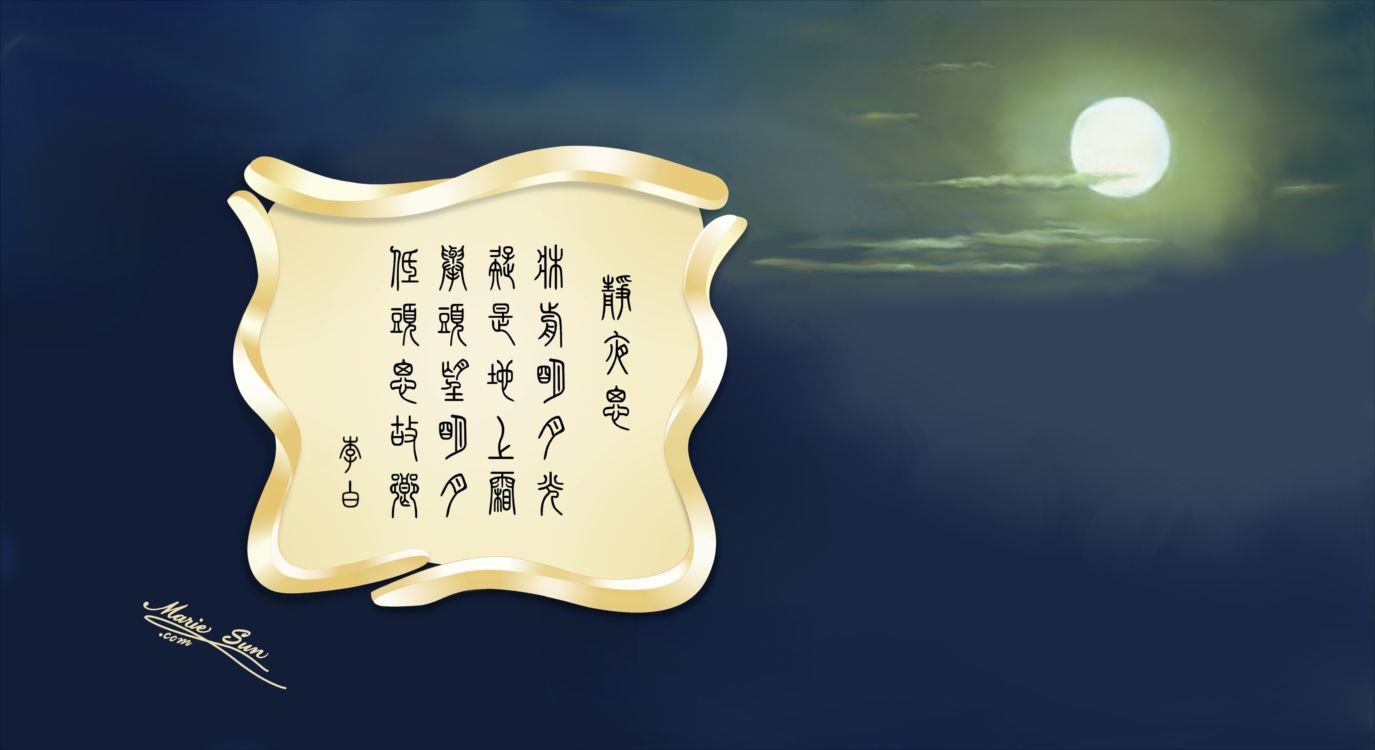

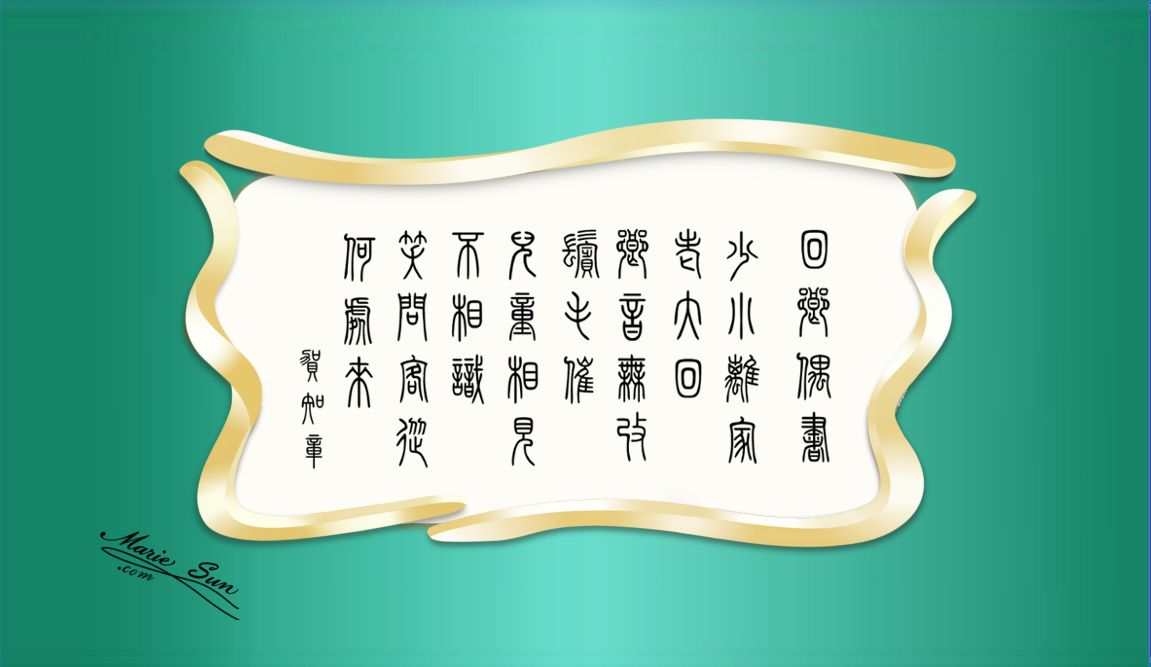

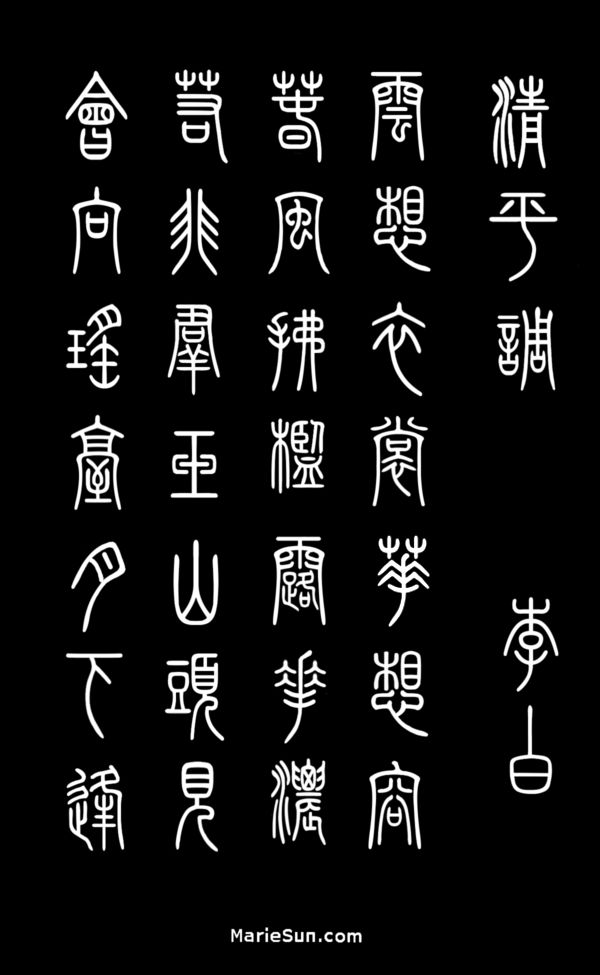

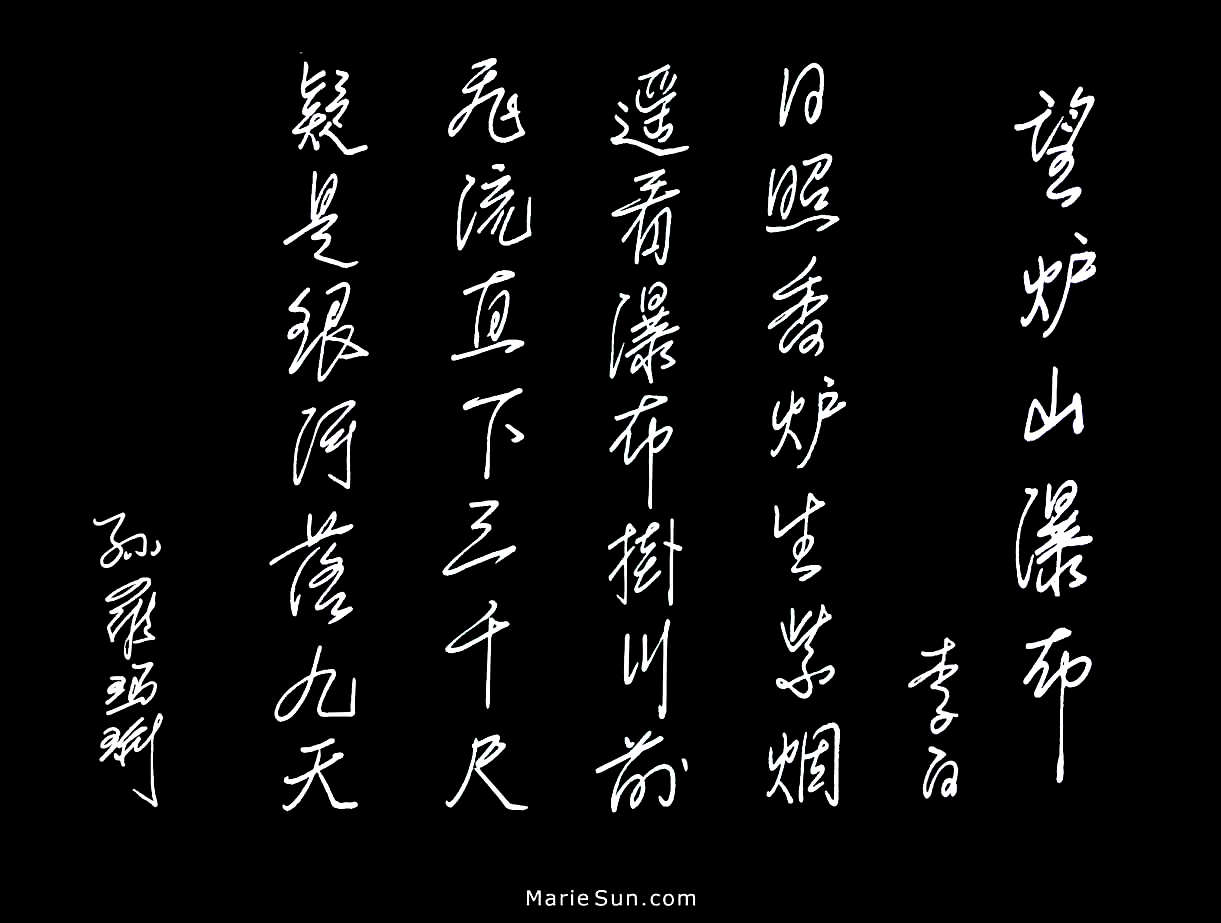

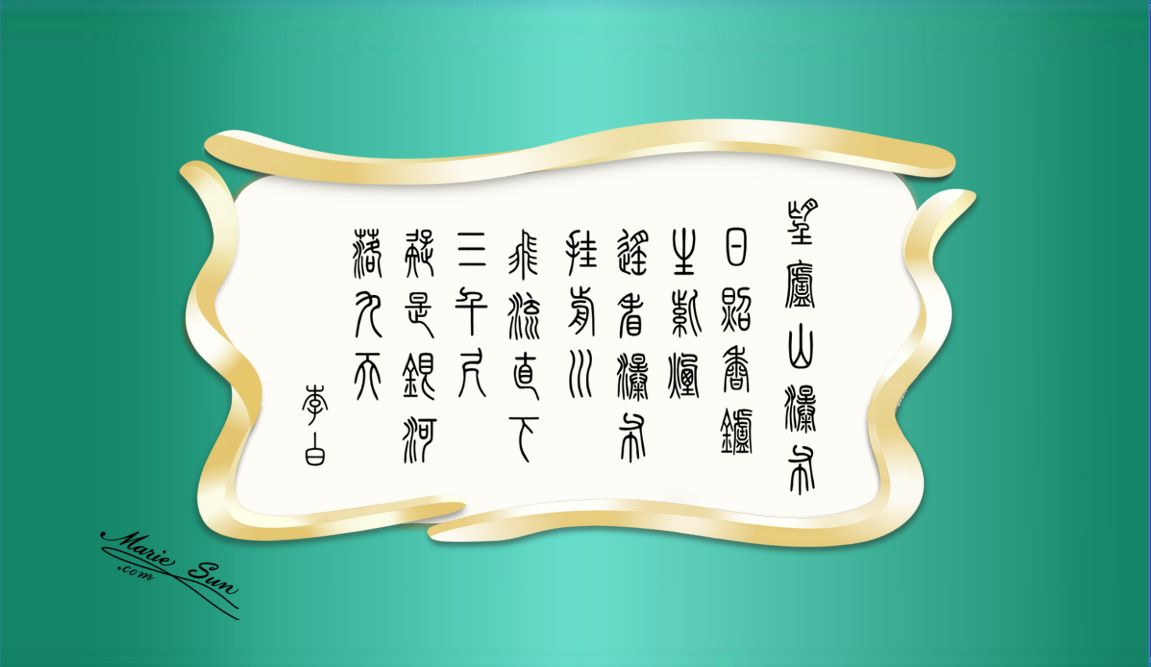

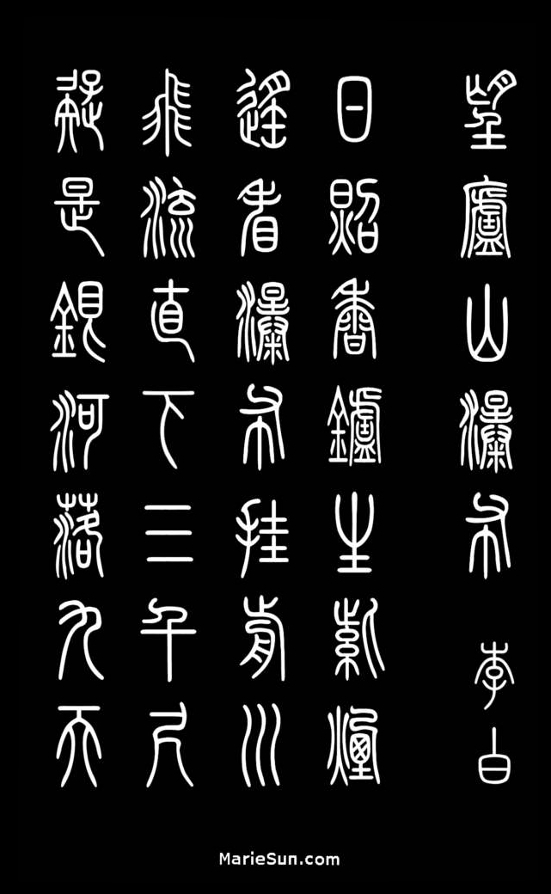

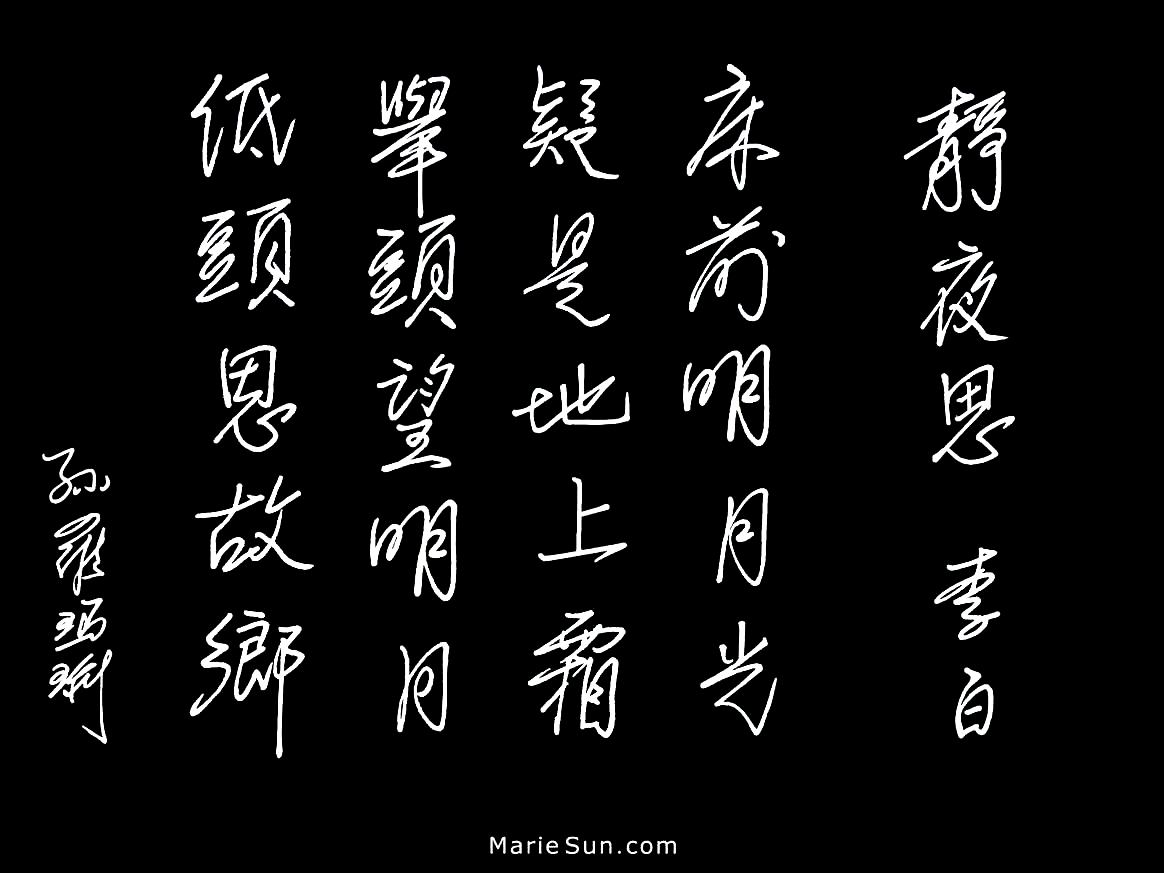

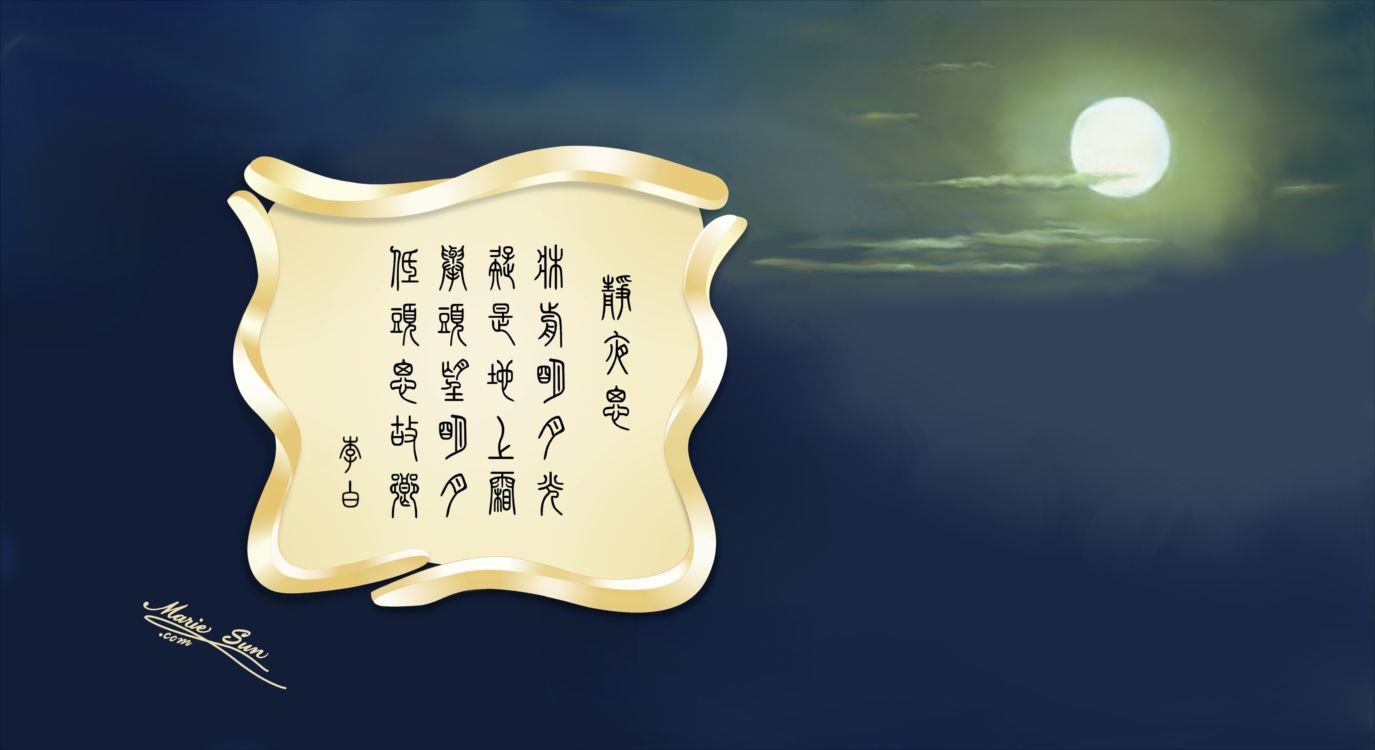

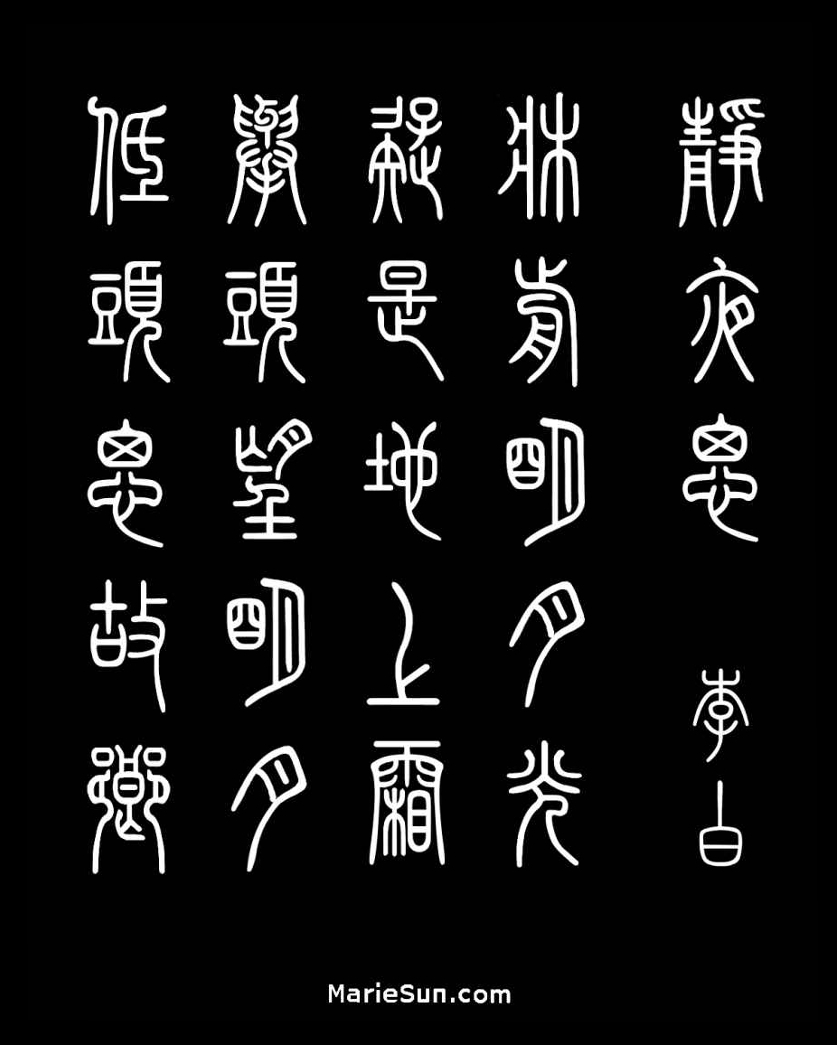

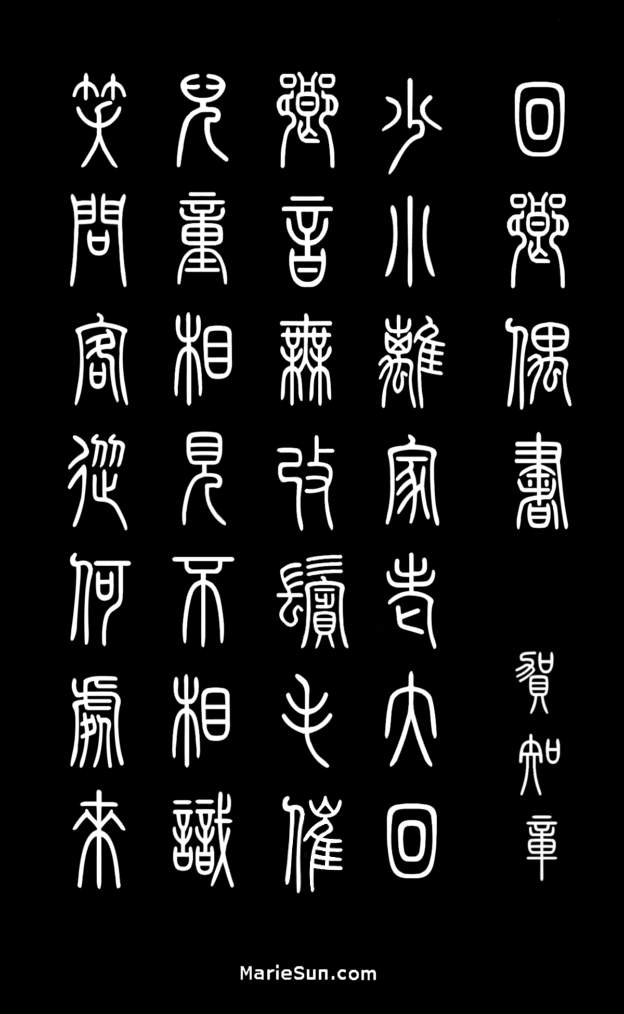

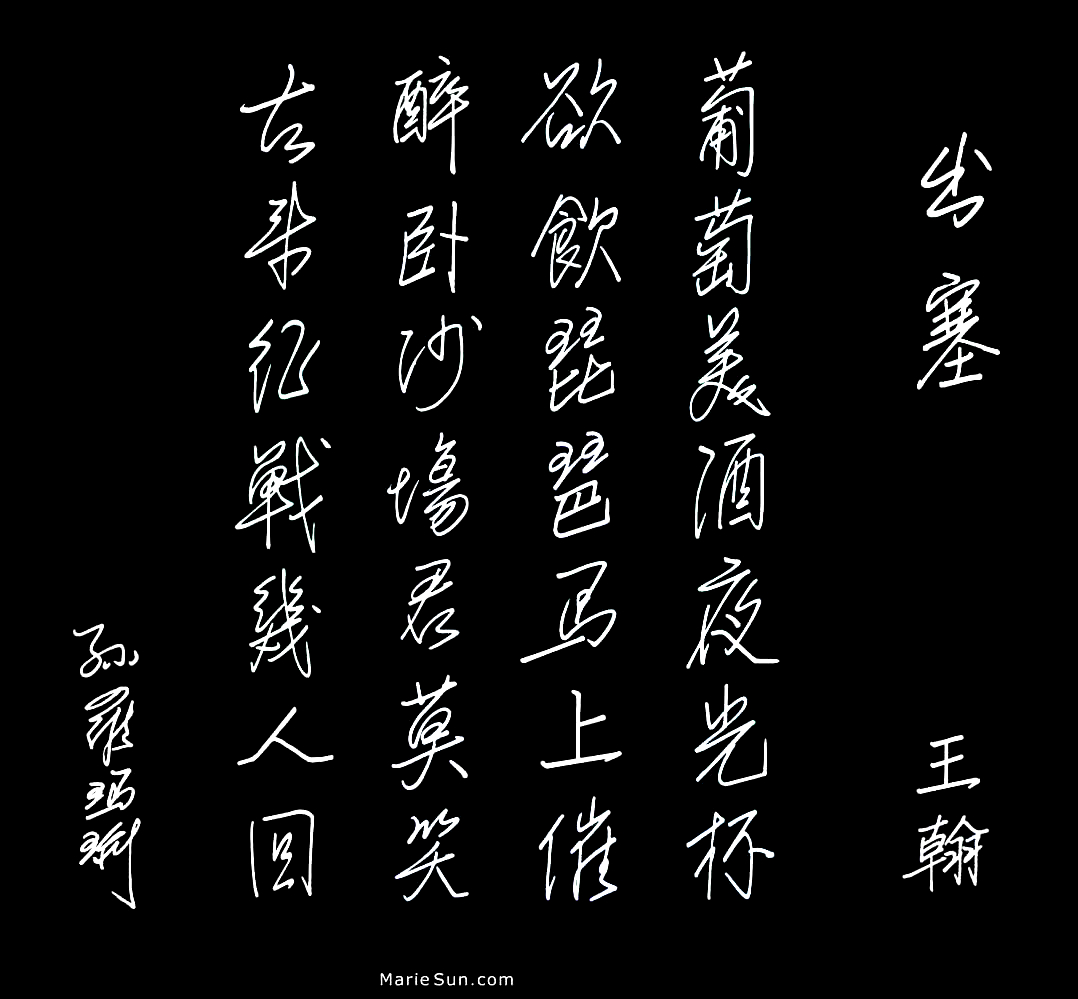

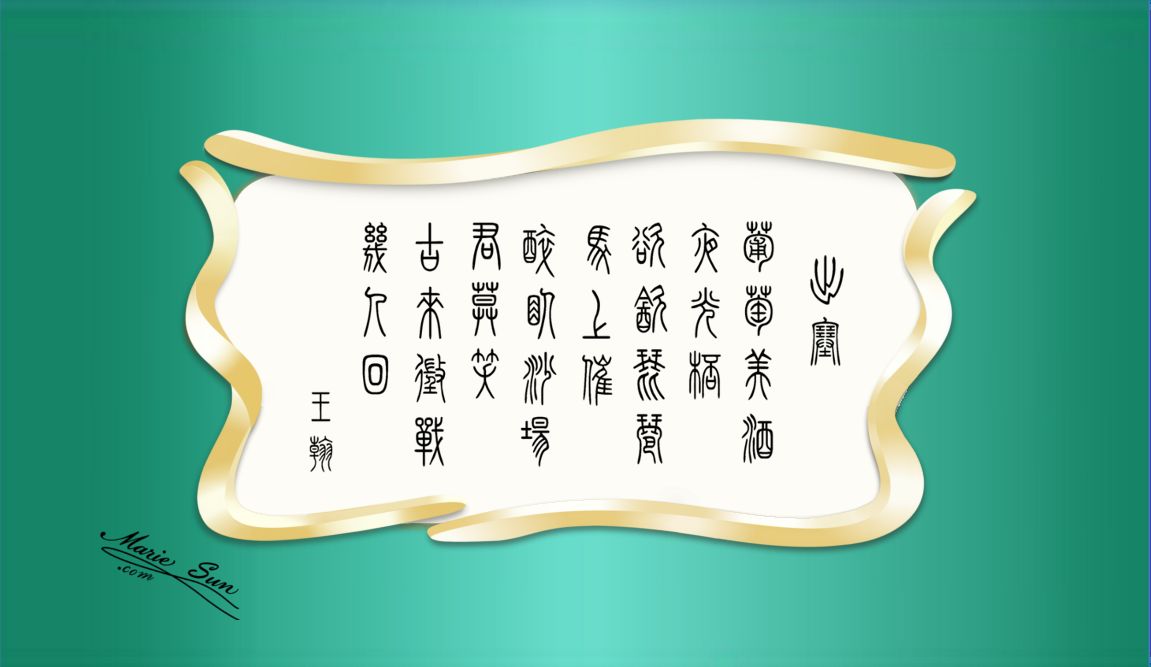

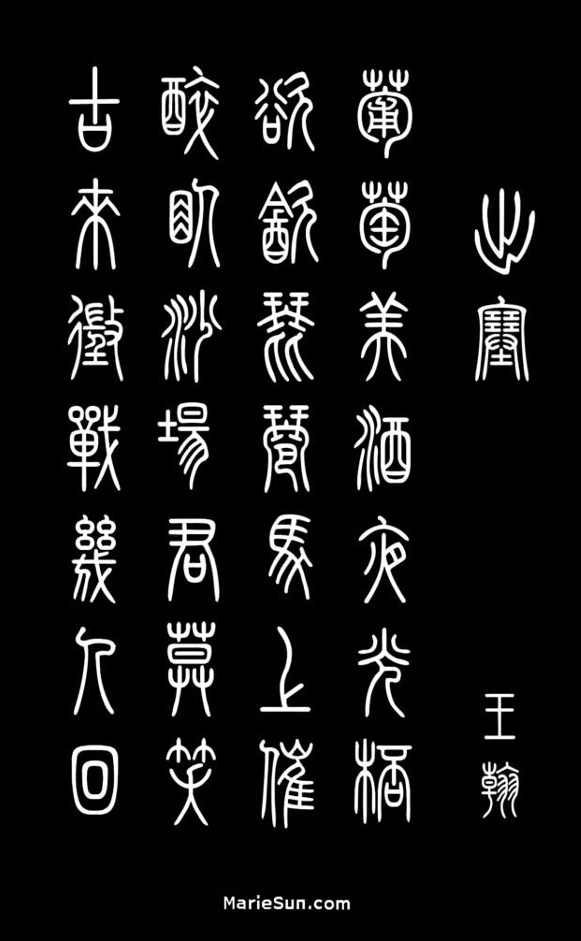

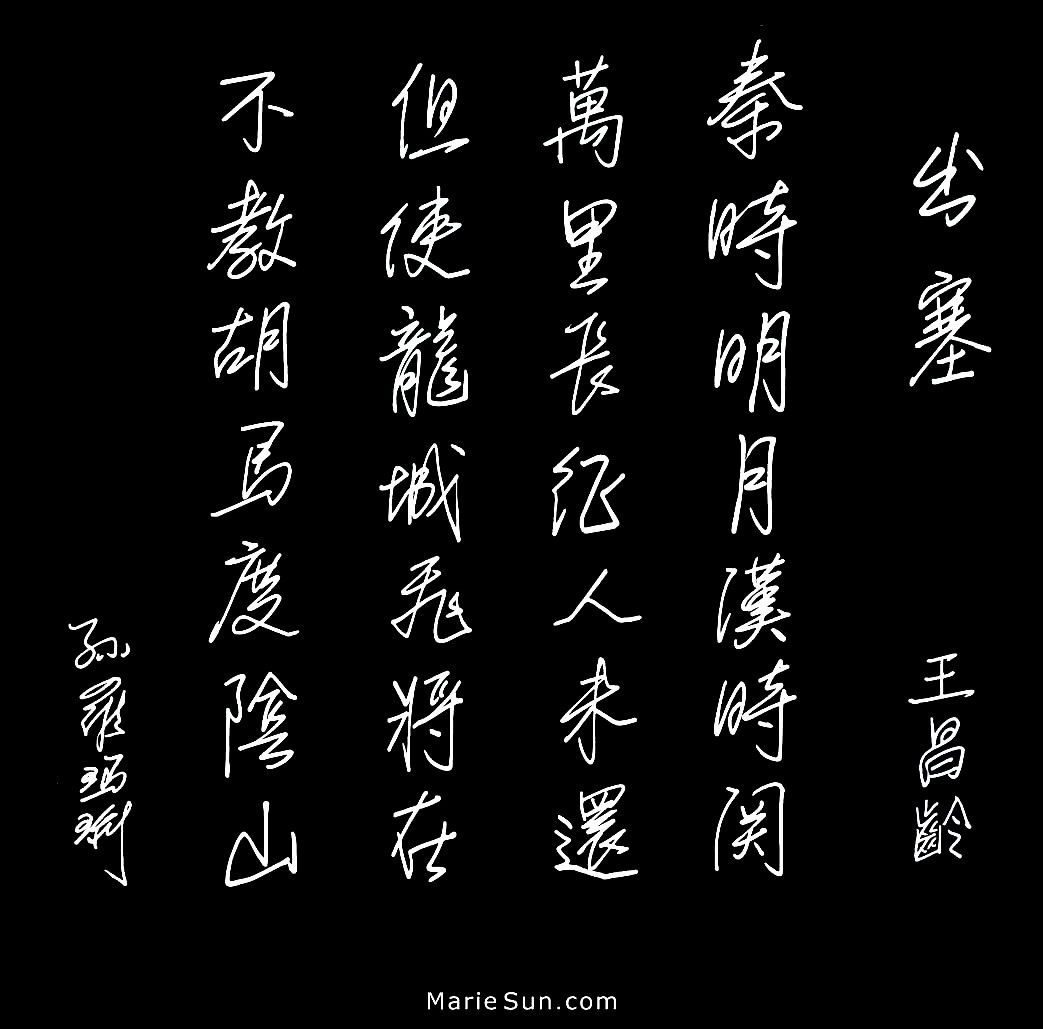

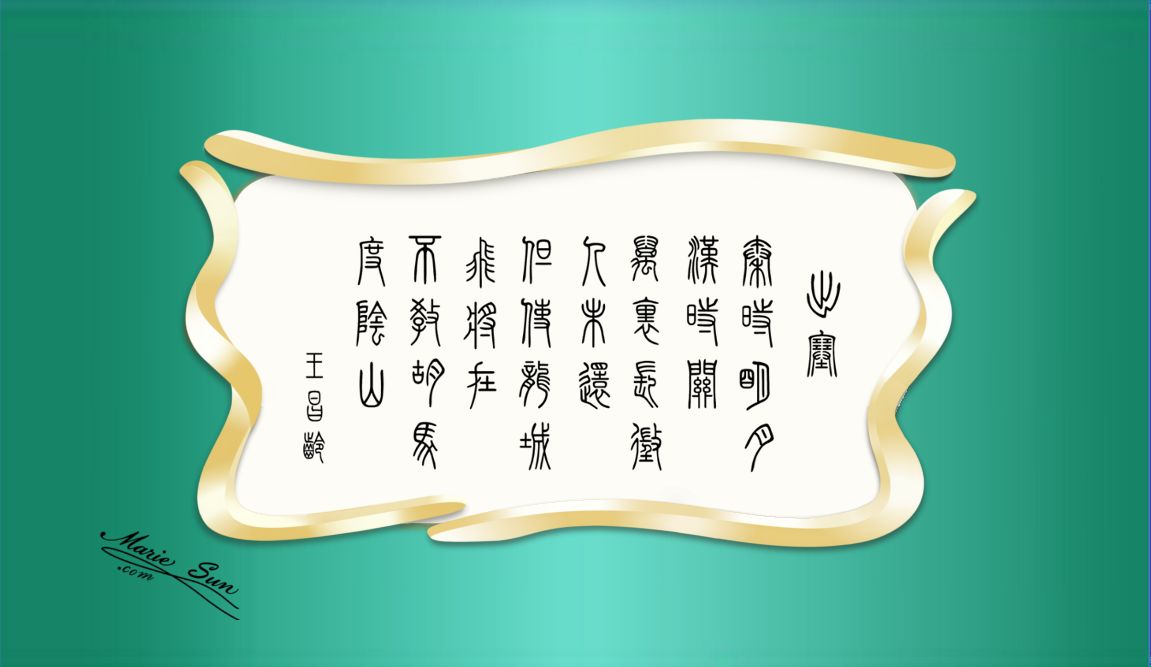

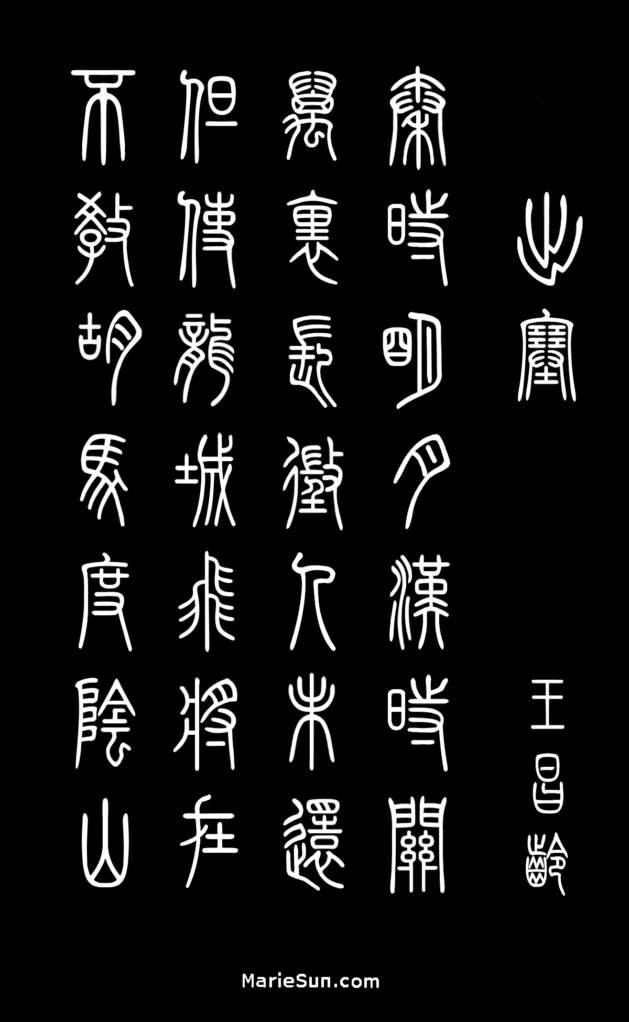

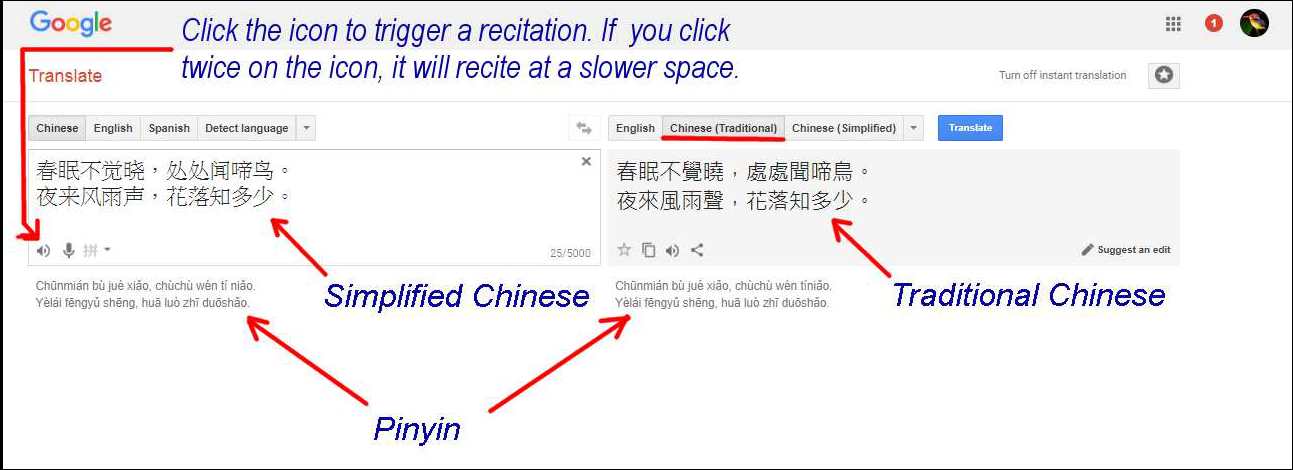

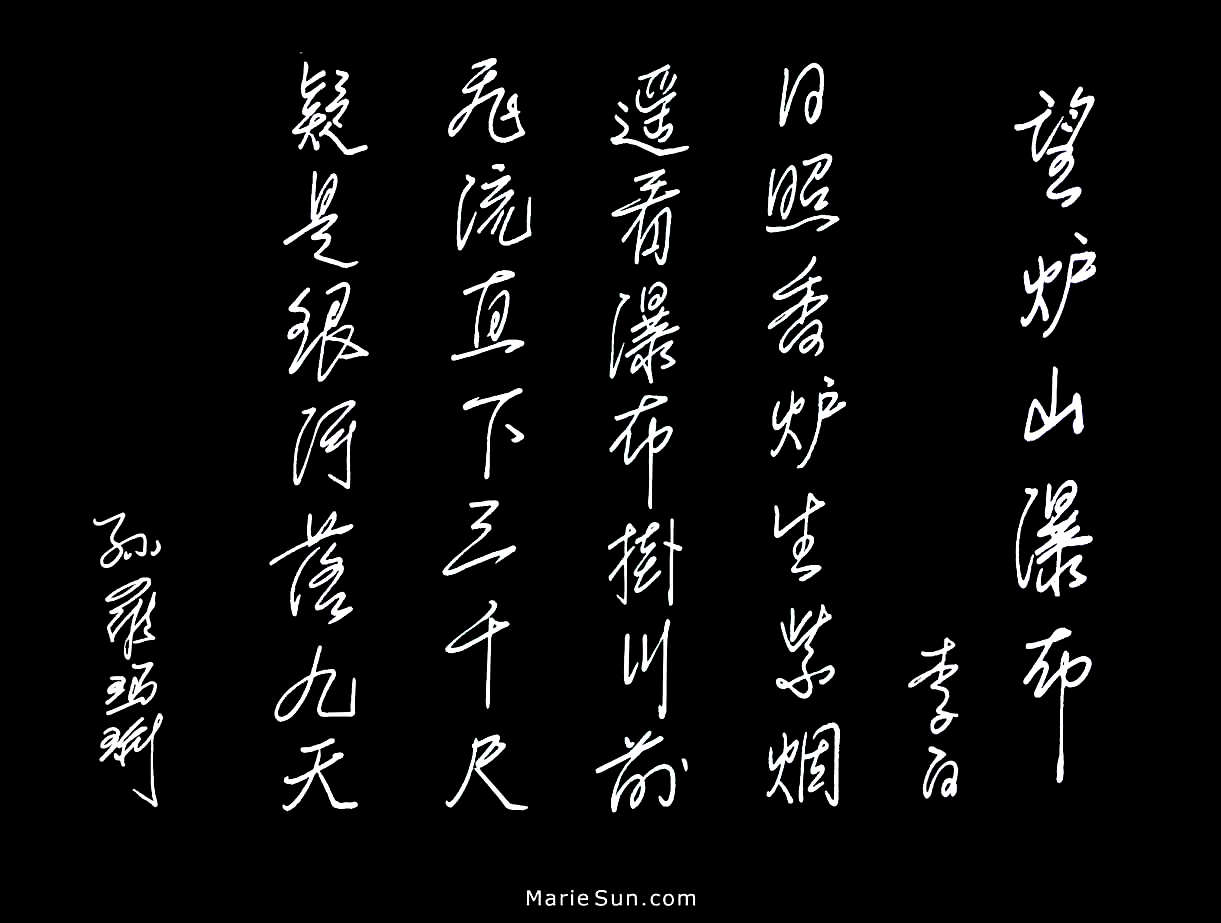

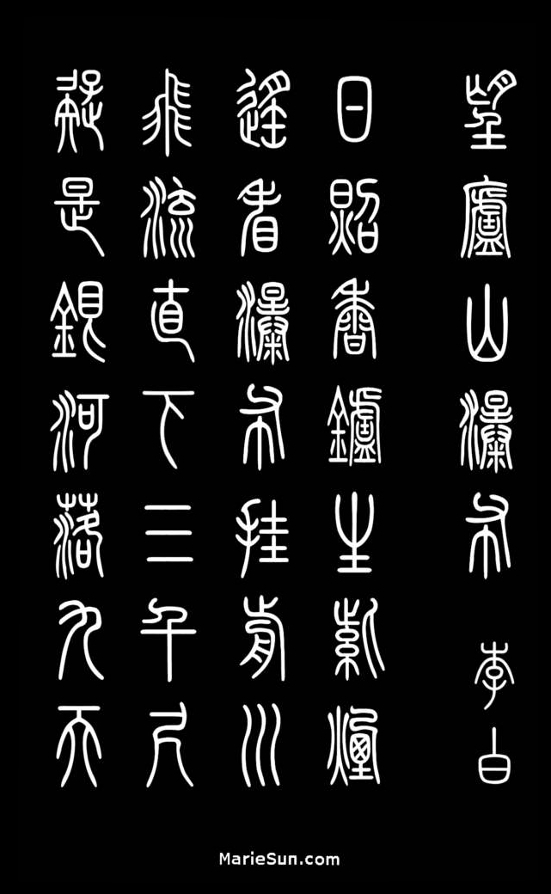

(2). Representation of each poem in xingshu 行书 calligraphy; in addition, 12 poems are also presented in zhuanshu 篆书 calligraphy.

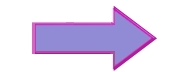

(3). Both traditional and simplified Chinese forms of the poem with pinyin annotations

(4). Recitation in mandarin for each poem

(5). Comments on the historical backdrop of the poem

(6). A glossary of terms and names mentioned in the poem

(7). images or videos relating to the poem or poet

About the Poems:

The 25 poems covered in this book are chosen out of the most popular

Chinese poetry anthology of all time, namely, "Three Hundred Tang Poems" "唐诗三百首"

compiled by Sun Zhu 孙洙 (1711 - 1778).

Most of the poems are presented after a brief biography of the poet. Because of the extensive background information being provided for Li Bai and Du Fu , however, their sections are arranged a little differently; most of their poems are presented at key points in their biographical narratives that inspired the given poem.

Except for Meng Haoran, Li Bai, and Du Fu, all poets are listed roughly in chronological order.

Chapters

1. Poets and Poems

(1). Meng Haoran 孟浩然

Meng Hao'ran (689 or 691 - 740; lived during the Early and High Tang periods), a descendant of Meng Zi 孟子

(also known as Mencius, the famous Confucian philosopher) and grandfather of poet Meng Jiao 孟郊,

was born in

Xiangyang 襄阳 by the Han 汉 River in Hubei Province 湖北省 (Hubei, literally "lake 湖 north 北". The city is located to the north of Dongting Lake 洞庭湖 along the Yangtze River 扬子江/长江).

Meng was a famous landscape poet. Fifteen of his poems are included in the anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems."

He sat for

the imperial examination 科举,

attempting to attain the degree title of "jinshi" 进士 at age 40,

but failed. After his brief pursuit of a career as a local official, he mainly lived in and

wrote about the area in which he was born and raised. The local

landscape, history, and legends were the subjects of his many

poems. So, too, were his journeys.

More than 10 years Li Bai's senior (and Li Bai's idol), he befriended Li in later adulthood. Meng also befriended Wang Wei 王维,

Wang Changling 王昌齡, and Wang Zhihuan 王之涣, among other poets.

Li Bai wrote many poems in admiration of Meng, among which are two famous ones --

"Presentation to Meng Haoran", and

"Seeing Men Haoran off at Yellow Crane Tower". The latter is included in this book.

Meng Haoran, as a prominent

landscape poet, had a major influence on poetry in the Early Tang era. This influence also extended into neighboring Asian countries, especially Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

* * *

In ancient times, writings were engraved into stone slabs or "steles" in order to preserve their beauty. Others could then duplicate them through stone rubbings. Such duplicate copies were called taben 拓本 (pinyin: tàběn, stone rubbing).

Creating a taben stone rubbing:

View video thru www.youtube.com/watch?v=HIVD__IHTv0 (38 seconds) or

select one thru YouTube.

Throughout this book, the poems presented as images follow the traditional Chinese manner - written in vertical columns from top to bottom and from right to left without punctuation.

However, the rest of the contents are presented in the "modern" western approach, with characters in horizontal rows from left to right, with occasional punctuation.

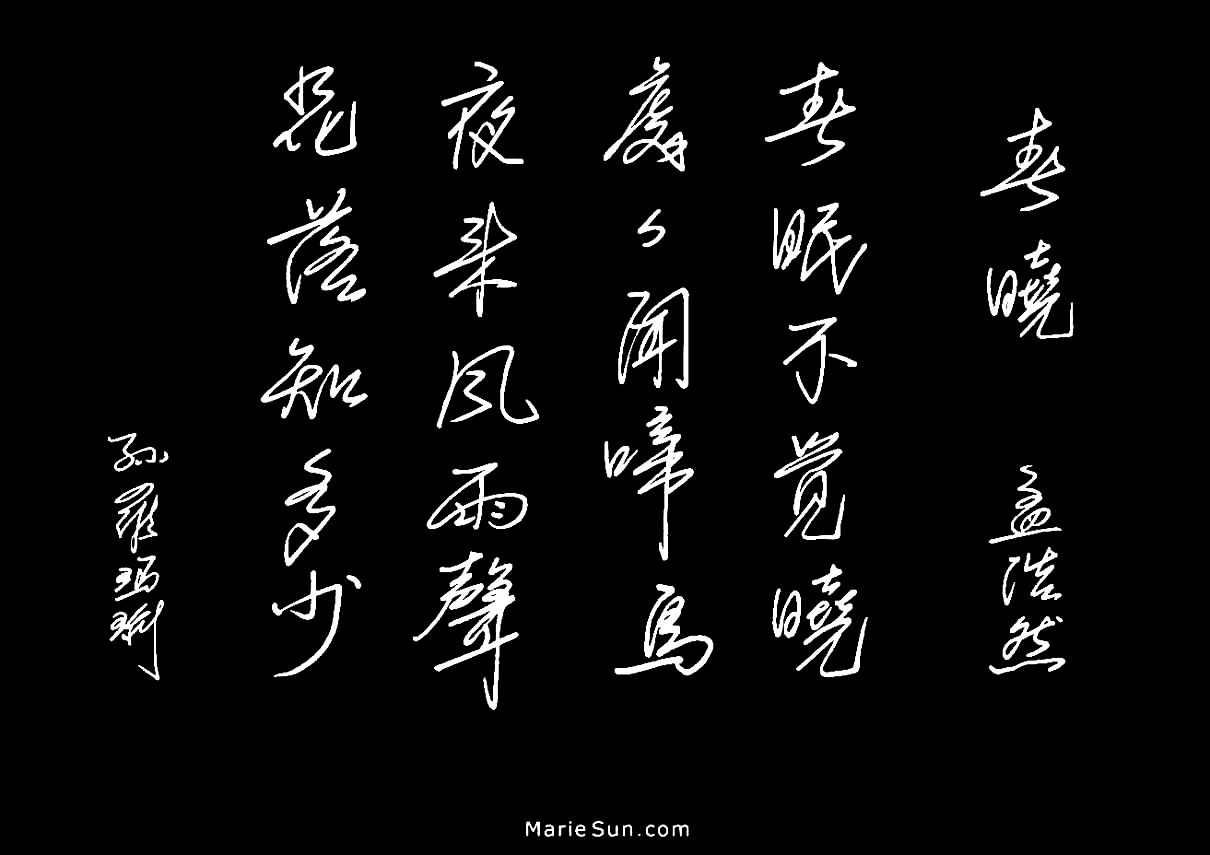

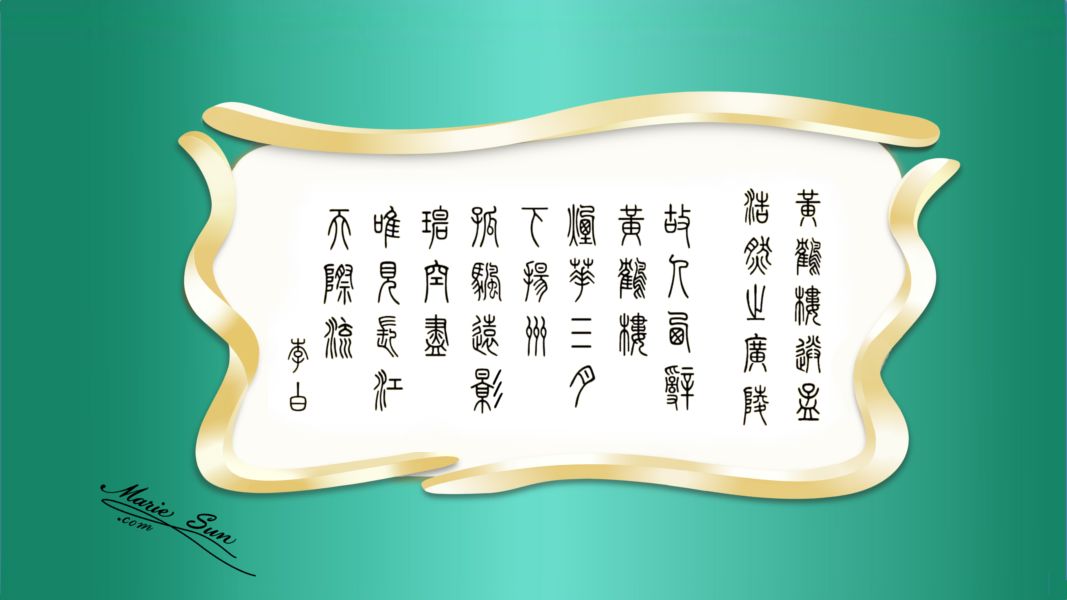

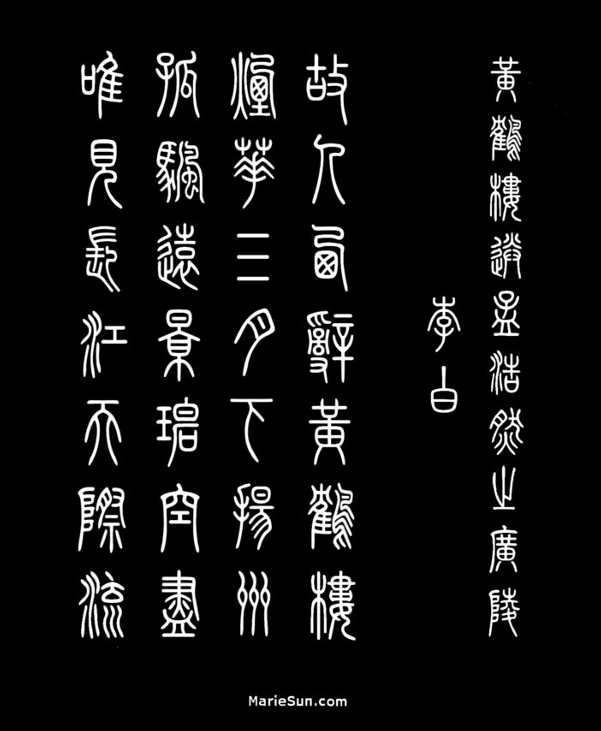

calligraphy in xingshu 行书 calligraphy:

calligraphy in zhuanshu/zhuanzi 篆书/篆字 calligraphy:

poem #01

Traditional Chinese

春曉 孟浩然

春眠不覺曉,處處聞啼鳥。

夜來風雨聲,花落知多少。

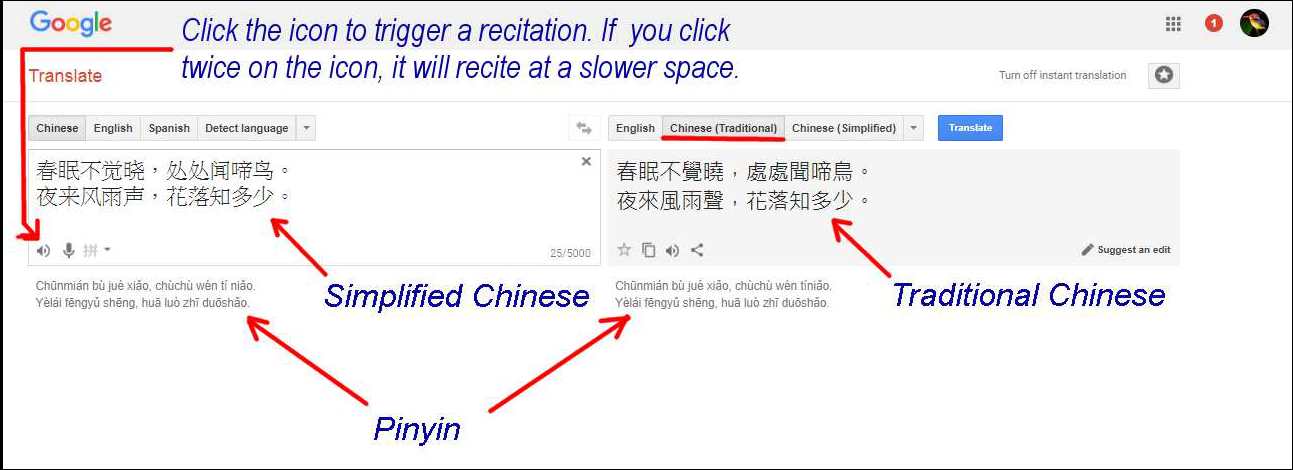

Simplified Chinese with *pinyin

春 晓 孟 浩 然

chūn xiǎo mèng hào rán

春 眠 不 觉 晓, 处 处 闻 啼 鸟。

chūn mián bù jué xiǎo, chù chù wén tí niǎo.

夜 来 风 雨 声, 花 落 知 多 少。

yè lái fēng yǔ shēng, huā luò zhī duō shǎo.

* Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Notes *:

Recitation 1: Click it to listen to a recitation of the poem in Mandarin Chinese

and to view a transliteration into pinyin through Google. If click twice on the speak icon, it will

recite at a slower pace.

Recitation 2: Click and select one of the options to listen to a recitation.

*pinyin 拼音

Each Chinese Character has only one syllable. There are about 50,000 Chinese characters

(a person need only master two to three thousand, however, to be able to read newspapers) and

tones are often used to differentiate words from each other. There are basically four tones in the Mandarin pinyin system. Examples for tones of "ma" would be (1) mā: mother 妈,

(2) má: hemp 麻, numb 麻 or mop 抹, (3) mǎ: horse 马 and (4) mà: scold 骂

The tones and cadence lead to the further enjoyment of the poems

as most of them are based on certain regulated

tone/cadence patterns and rhymes that enhance the ability of recitation and gracefulness. While reciting Tang poems in Mandarin is a delight,

it is even more so in the southern dialects of Chinese, such as Cantonese, which have preserved more closely the pronunciations and tones of the Tang period.

Spring Dawn Meng Haoren

Indolent sleeping in spring,

I'm unaware morning's here.

Clearly I can hear,

Birds' twittering everywhere.

With last night's gust of wind and rain,

I'm wondering -

How many flowers

Have fallen and scattered.

* * *

Meng used plain and simple

words to describe a spring morning scene.

His poems are often filled with charming descriptions of nature.

Most of his landscape poems reflect beings and objects coexisting in natural harmony.

This was a reflection of his own life and pursuits - to live in the world without harming it or attempting to "conquer" it. But, rather, to preserve it as it was, and to be part of it and enjoy it.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

If there are several meanings for a character or a term, the ones complying best to the poem's generally understood intent are listed first.

春晓: spring dawn 春: spring 眠: to sleep, to hibernate 不觉: unaware, hard to sense, unconsciously 晓: dawn, daybreak, to know, to tell

处处: everywhere, in all respects 闻: to hear, to smell, to sniff at 啼: to twitter, to sing, to cry, to weep aloud, to crow, to hoot

鸟: bird 啼鸟: bird's chirping, bird's twittering, bird's singing

夜: night 来: come, return 风雨: wind and rain 声: sound, voice, tone, noise

花: flower, blossom 落: fall, drop 知: to understand, to know, to be aware 多少: how many, how much, which (number), number, amount, somewhat

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Chinese calligraphy 春眠不觉晓书法:

view thru Google,

Baidu or

Yahoo Japan.

2. Xiangyang, Hubei Province 襄阳, 湖北省 - Meng Haoran's hometown:

View thru Google or

Baidu.

(2).

Li Bai 李白

Li Bai (701 - 762; lived mostly in the High Tang period and only a few years into the beginning of Mid Tang period), the most famous romantic poet in Chinese history, penned numerous masterpieces that are still memorized and chanted by Chinese of all ages today. He went by many names; his most popular and well-known title being Shi Xian 诗仙 - "the Poet Immortal" or "the Poet Transcendent”. His name has also been romanticized as Li Po or Li Bo. Thirty-four of Li Bai's poems are included

in the popular anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems,"

second only to Du Fu's thirty-nine poems.

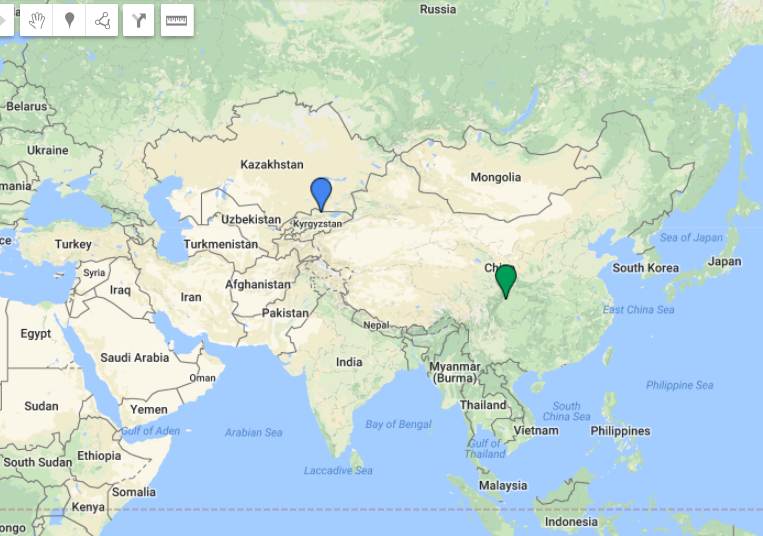

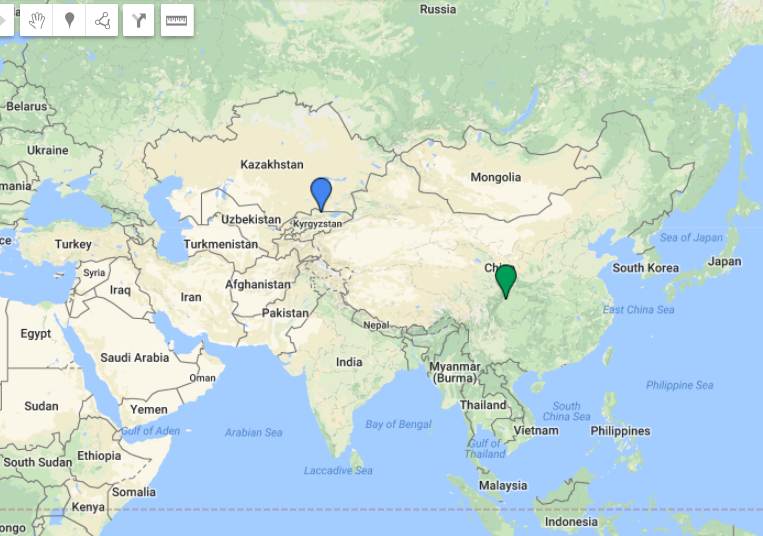

Li Bai's ancestors were from Longxi, Chengji

陇西, 成纪, in present-day northern Qinan county, Gansu Province 秦安县北, 甘肃省. They were banished to Tiaozhi 条枝 in the Western Regions 西域, today's Central Asia, during the Sui Dynasty by the Sui ruler.

As for Li Bai's birth place, according to Guo Moruo 郭沫若, a historian and ancient writing scholar, Li Bai's ancestors moved from Tiaozhi to a prosperous silk trading city Suiye 碎叶, also in Central Asia, within the Ansi Protectorate 安西都护府, and Li Bai was born over there. Suiye was

also known as Suyab, once a flourishing trading city on the Silk Road and now an archaeological

site in modern day Ak-Beshim, Kyrgyzstan.

View present-day Ak-Beshim (Suiye) in

Kyrgyzstan

thru Google or

Yahoo.

View details regarding

Ak-Beshim:

Wikipedia.

Li Bai's father, Li Ke 李客, was probably a very successful merchant, since the family was installed in one of the thriving commercial centers of the empire. In 705, Li's father moved the family back to China and settled down in Jiangyou, Sichuan Province 江油, 四川省. (

View Jiangyou thru Google or

Baidu.)

(Jiangyou is bordered on the northeast side by Mianyang City 绵阳市 - today's "Silicon Valley" in China.)

Speculated birthplace of Li Bai- Suiye (the blue drop shape) and his second "hometown" (the green drop shape):

(Source: Google Map)

The young Li Bai read extensively, devouring not just Confucian classics, but

also various tracts on astrological and metaphysical subjects, including the Chinese classic text -

Tao Te Jing/Dao De Jing 道德经 (Wikipedia).

He was also skilled in swordsmanship.

His place of birth, his tall girth, and his angular

facial features, suggested that he was possibly of mixed race. It was said that he was conversant in at least one foreign language due to his background and upbringing.

In 725 at age 24, Li Bai left his second hometown, Jianyou, to explore the world. Being young, ambitious,

and without

financial constraint, he embarked on a knight-errant-like journey. Heading east down the Yangtze River, while passing through the Jingmen Gorge, he left behind a beautiful poem "Bid Farewell at Jingmen" 荆门送别. He explored

Jiangling 江陵 in Hubei 湖北 Province, Dongting Lake 洞庭湖 in Hunan 湖南 Province, Mount Lu 庐山 in Jiangxi 江西 Province,

and Jingling 金陵 (present-day Nanjing 南京) in Jiangsu 江苏 Province. Along the way he met and befriended various poets and social elites, including Meng Haoran, who Li Bai had long admired.

Li Bai wrote several poems in admiration and praise of Meng, including the following:

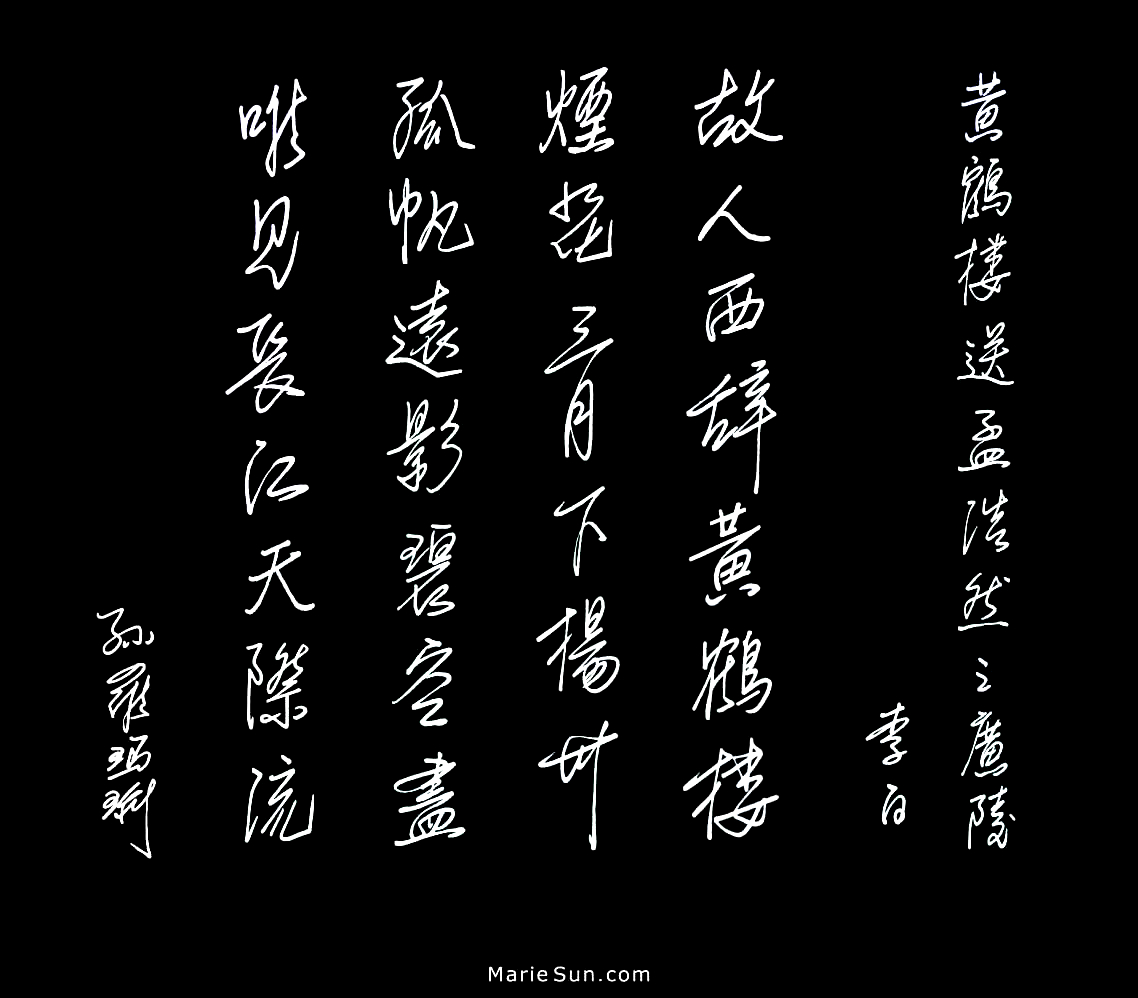

poem #02

Traditional Chinese

黃鶴樓送孟浩然之廣陵 李 白

故人西辭黃鶴樓,

煙花三月下揚州。

孤帆遠影碧空盡,

唯見長江天際流。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

黄 鹤 楼 送 孟 浩 然 之 广 陵

huáng hè lóu sòng mèng hào rán zhī guǎng líng

故 人 西 辞 黄 鹤 楼,

gù rén xī cí huáng hè lóu ,

烟 花 三 月 下 扬 州。

yān huā sān yuè xià yáng zhōu 。

孤 帆 远 影 碧 空 尽,

gū fán yuǎn yǐng bì kōng jìn ,

唯 见 长 江 天 际 流。

wéi jiàn cháng jiāng tiān jì liú 。

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Seeing off Meng Haoran for Guangling at Yellow Crane Tower Li Bai

My old friend departs the west at Yellow Crane Tower,

On a journey to Yangzhou among March blossom flowers.

His lonely sail receding against the distant blue sky,

All I see but the endless Yangtze River rolling by.

* * *

In the spring of 728 at age 27, Li Bai heard that Meng Haoran

was going to take a trip to Yangzhou 杨州. Li Bai managed to travel to present-day Wuchang city in Hubei Province 武昌市, 湖北省

to meet with Meng for several days of adventure, after which they parted at the nearby Yellow Crane Tower. Li Bai wrote this famous poem describing the melancholic nature of his idol's departure.

The poem is filled with affection and paints a vision of a brilliant spring day pushed to the horizon by the endless and powerful Yangtze River. It is a vision and a force that also carries away the ardent heart of the poet as he watches his idol's lone boat vanish into the distant horizon.

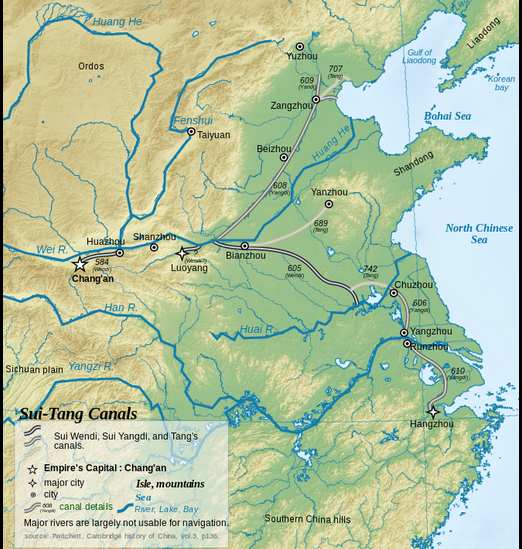

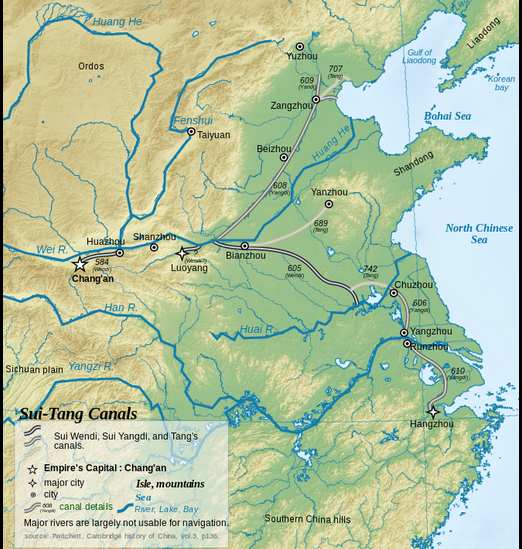

Yangzhou (marked as number 1) is located near the eastern terminus of the Yangtze River. The Yellow Crane Tower lies between Chongqing and Yangzhou:

(This map may be freely copied from www.mariesun.com for educational or noncommercial purposes of uses with a reference to "Marie Sun and Alex Sun at MarieSun.com".)

The map's outline is provided by

Joowwww [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

黄鹤楼 The Yellow Crane Tower:

A famous, historical tower, it was first built in 223 AD, on Sheshan in the Wuchang District of Wuhan, Hubei Province 武昌区,武汊, 湖北省 by the Yangtze River. Warfare and fire destroyed the tower many times and it has been rebuilt several times.

扬州 Yangzhou: Located northeast of Nanjing, Jiangsu Province 南京, 江苏省.

The distance from Yellow Crane Tower to Yangzhou is about

330 mi/483 km (mi: miles, km: kilometers) as the crow flies, 460 mi/736 km as the river winds.

Historically it was one of the wealthiest cities in China, known for its great merchant families,

poets, painters, and scholars.

广陵 Guangling: An old name for Yangzhou.

长江 Changjiang:

Also known as the Yangtze River 杨子江. According to year 2017 statistics, it is the longest river in Asia, and the third longest in the world after the Nile and Amazon Rivers. It flows for about 3,900 mi/6,280 km from the glaciers of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau eastward across southwest, central, and eastern China before emptying into the East China Sea at Shanghai.

送: to see off , to send, to deliver, to carry, to give (as a present) , to present (with), 之: to

故人: old friend, the ancient 西: west

辞: to depart, to leave, to resign, to dismiss, to decline, to take leave, words, speech

烟花: full bloom of flowers, fireworks,

三月: March 下: going down, traveling down

孤: lone, lonely 帆: sail 远: far, distant, remote

影: shadow, picture, image, reflection,

碧空: the blue sky, the azure sky

尽: to the utmost, to end, to use up, to exhaust, to finish, exhausted, finished, to the limit (of something), to the greatest extent, extreme, within the limits of

唯: only, alone 见: to see, to meet

天际: horizon 流: to flow, to disseminate, to circulate or spread, to move or drift

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Chinese calligraphy 黄鹤楼送孟浩然之广陵书法:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

2. Changjiang/Yangtze River 长江/揚子江:

View thru Google,

Baidu,

Yahoo,

Yahoo JP

or

Bing.

3. They parted at the Yellow Crane Tower 黄鹤楼:

View the tower as of today thru Google or

night scene thru Baidu.

4. Meng Haoran visited the beautiful city of Yangzhou 扬州, which was the most prosperous city in the

Jiangnan 江南

region during the Tang Dynasty. "Jiangnan" literally means "River South", or "the Yangtze River South". Although Yangzhou lays on the north bank of the Yangtze River, it became associated with the Jiangnan region by dint of its sheer wealth and prosperity.

View Yangzhou thru Google,

Baidu,

Yahoo,

Yahoo JP,

Google Hong Kong,

or

Bing.

5. Being prosperous, Yangzhou has always been famous for its dessert dim sum:

View thru Google

or

Baidu.

While touring Hubei, Li Bai was introduced by friends to the family of the former Prime Minister Xu Yushi 许圉师.

Li, at age 26, was young, handsome, and well-built. He excelled at both swordsmanship and literature, and had about him a chivalrous and gentlemanly demeanor. A budding poet, he was well-received by Xu's family and eventually married the former Prime Minister's granddaughter, Xu Ziyan

许紫烟. The couple settled down at Peach-flower Rock, near Li's in-laws in present-day

Anlu, Hubei Province 安陸, 湖北省.

Although Li Bai would travel from time to time or take short mountain sabbaticals (to enhance study and reflection) for the purposes of obtaining a position in the imperial court, the couple led a content married life with little financial burden, with Xu Ziyian bearing a daughter, Li Pingyang 李平阳, and a son, Li Boqin 李伯禽.

While away from home,

Li Bai wrote many letters and poems to his wife

to express his loneliness and longings, some of which were very witty and humorous.

The blessed marriage lasted for 12 years. In 740, Xu Ziyian passed away. Since several of Li's close relatives lived in Renchen

任城, located on the south side of present-day Jiling city, Shandong Province 济宁市, 山東省, Li Bai moved his family there. This was not far from Lu county, where Confucius' hometown is located.

After settling down at Renchen, Li Bai managed to spend some time living in seclusion with five other hermits on Mt. Culai

徂徕山 (

view Mt. Culai thru Google

or

Baidu).

They settled by a scenic brook in a bamboo forest, and hence the six of them earned a collective name - "The Six Hermits of Leisure of the Bamboo Brook" 竹溪六逸. Needless to say, Li Bai spiritually enjoyed his time there, taking in the surrounding mountain scenery, drinking wine, enjoying tea, playing music, practicing his fencing, and especially chanting poems together with his like-minded companions. While living on Culai Mountain, Li Bai continued to maintain contact with the local intelligentsia and gentry through letters and visits in order to get his name heard. This was the fashion during Tang Dynasty for ambitious scholars to obtain a central government appointment in the imperial court. Li Bai lived on Culai Mountain intermittently on three separate occasions.

Mt. Culai, the sister mountain of Mt. Tai 泰山, lies about 12.5 mi/20 km

to the southeast of Mount Tai. In Chinese feudal tradition, emperors would come to this area atop Mt. Tai and hold Heaven-and-Earth worship ceremonies 祭天祭地, also called fēngchán 封禅, during prosperous periods to pay gratitude to Heaven and Earth. Another main purpose was to justify and reify their "superpower" and authority over their people. After the ceremony, the emperors would also often stop at nearby Qufu 曲阜 in Lu county, the birthplace of Confucius, to hold a ceremony honoring him 祭孔大典.

Early in the Han Dynasty, Emperor Han Wudi 汉武帝 had paid three visits to the area, performing the aforementioned ceremonies. Several Tang emperors did so as well. Emperor Tang Ming Huang performed the ceremonies for the first and only time in 725, the year Li Bai was just stepping out of Sichuan to explore the world. While holding ceremony in Lu county, Tang Ming Huang composed a poem called "Passing through Zou Lu and offering a sacrifice to Confucius with a sigh" "经邹鲁祭孔子而叹之". This is the only poem by the emperor, himself, that is included in the anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems".

Living on nearby Culai Mountain and cultivating a reputation as a learned, self-sufficient, capable man, Li Bai provided himself the chance of being recognized and introduced to the Tang emperor during these ceremonies and would have had the opportunity to be possibly "fast track" into the imperial service.

Before his wife passed away, Li had lived in seclusion on several other mountains as well. One of these was

Zhongnan Mountain 終南山 (

view the mountain, hermits and monks thru Google or

Baidu,)

about 10 miles south of the Tang capital of Chang'an. He lived there around age 29 for less than a year. During the early Tang, the famous scholar hermit Lu Cangyong 卢藏用 lived on this same mountain and was called in by

Empress Wu Zetian 武则天

to work for the central government. Lu began at the position of a remonstrative official - Zuoshiyi 左拾遗 (

duties of remonstrative officials in the Tang Dynasty

and

rank schedule of the imperial civil service system), working his way up quickly to the Shangshu-Youcheng 尚书右丞 level, i.e., almost to

the position of prime minister. This is the origin of the Chinese idiom "Zhongnan Fast Track" "终南捷径". Li Bai, however, did not meet with such fortune on Zhongnan Mountain.

In 742, Hè Zhizhang 賀知章, about 83 years old at the time a leading light of literature and high-level imperial official, read Li's poems, marveled at his literary talent, and praised Li Bai as the "Transcendent Dismissed from Heaven" or

"Immortal Exiled from Heaven"

"謫仙人". From this point forward the acclamation "Li Bai, the 'Transcendent Dismissed from Heaven' " began to spread throughout the empire. And the two cemented the bond of a lifelong friendship.

In the late summer of the same year, Emperor Tang Ming Huang, who had caught wind of Li Bai's reputation, summoned him to the the capital Chang'an for an audience. From Li Bai's home to Chang'an was nearly a distance of 600 mi/965 km, as the crow flies. Li did not arrive until the autumn.

Emperor Tang Ming Huang, an expert on military strategy who also excelled at literature, greeted Li Bai at the Grand Palace in person. During the banquet, Li's personality, wit, and political views fascinated Tang Ming Huang. The emperor even personally seasoned the soup for Li Bai.

The next year, Li Bai was assigned a

Hanlin 翰林

position at the Hanlin Academy

翰林学院 within the imperial court and appointed the state Grand Secretary.

As a result of the emperor's favor, Li was never required to take the imperial examination to attain the title of jinshi, a usual prerequisite for selection and assignment to a Hanlin position. Indeed, Li Bai never attempted to take the

imperial examination at all.

It was rumored that this was because his ancestors had been banished to Central Asia for some kind of crime. The norm at the time was that offspring of criminals were automatically disqualified from taking the exam, but his ancestors were banished in the Sui Dynasty (581 - 618)

and the Sui was overthrown by the Tang in 618, some 80 years before Li Bai was born!

Being from a merchant family also would have disqualified him from taking the imperial examination, though. This policy was adopted most likely to prevent collusion between government employees and businessmen. But in reality, this policy was never consistently implemented. Highly wealthy merchants could always circumvent the rules and secure important government positions. One such example was Wu Shiyue 武士彠, a successful lumber businessman with good connections to the Tang royal family, who secured several important government positions early during the dynasty and indirectly helped his daughter -

Wu Zetian 武则天

“usurp” the throne. This regulation was eventually repealed by the following Song (Sung) Dynasty 宋朝, and almost all classes of males (and only males) were thereafter permitted to take the exam. In any event, during Li Bai's lifetime he often broke from convention and followed his own path.

In the beginning, Li led a fairly pleasant life at court. The famous verse "Guifei grinding ink, Lishi pulling off boots" "贵妃磨墨, 力士脱靴" describes this period. It depicts Yang Guifei 楊貴妃, Tang Ming Huang's most adored consort, grinding Chinese black inksticks into ink for Li to pen down a poem, while Gao Lishi 高力士, Tang Ming Huang's favorite

eunuch 宦官,

(and the most politically powerful figure in the palace), assists in pulling off Li's snow stained boots under Tang Ming Huang's request. All to facilitate Li’s comfort and creative genius. It was also suggested that whenever Li Bai published a new poem, there would be a run on paper in Chang'an, sending the price soaring, with everyone rushing out to obtain copies of his new work.

Li's main duty was to handle secretarial works and record tasks for Tang Ming Huang, which included accompanying Tang Ming Huang to important ceremonies and festivities and documenting them. Tang Ming Huang probably intended that through Li's exquisite writing, the records of his reign would be of particular interest to future historians and scholars.

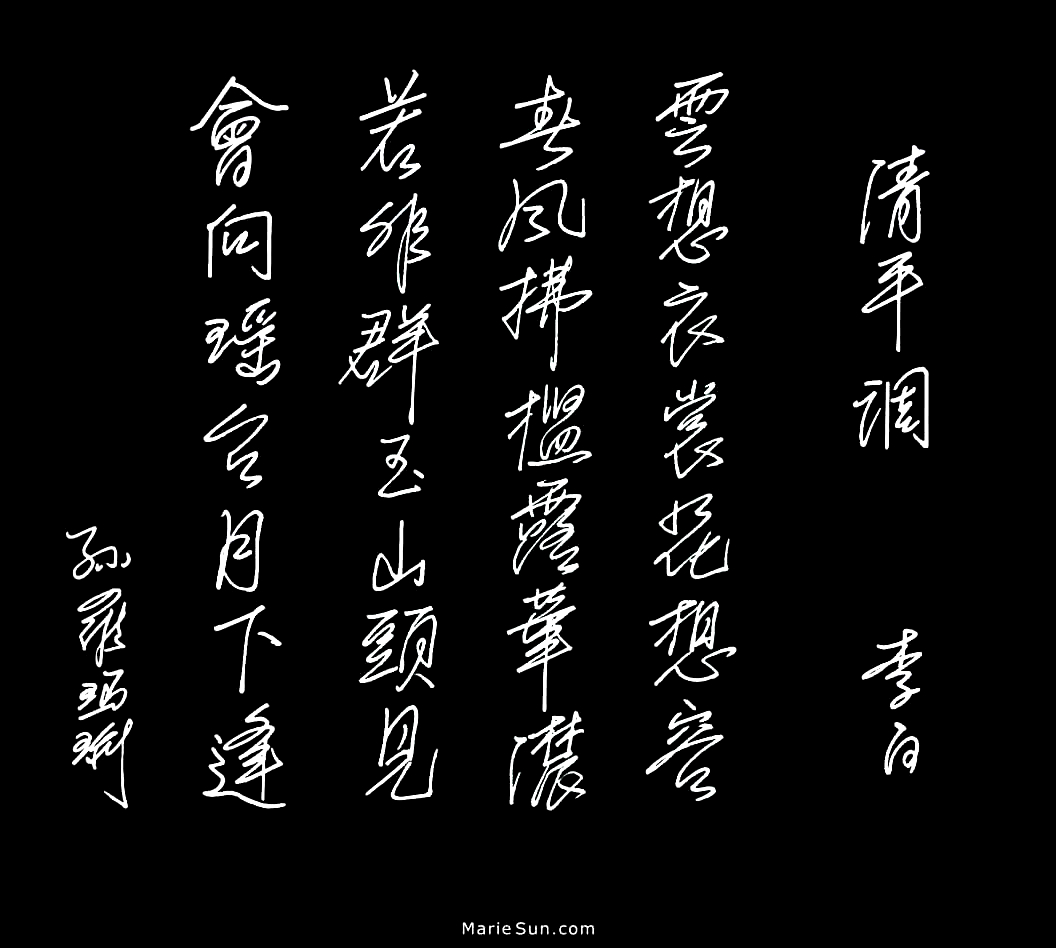

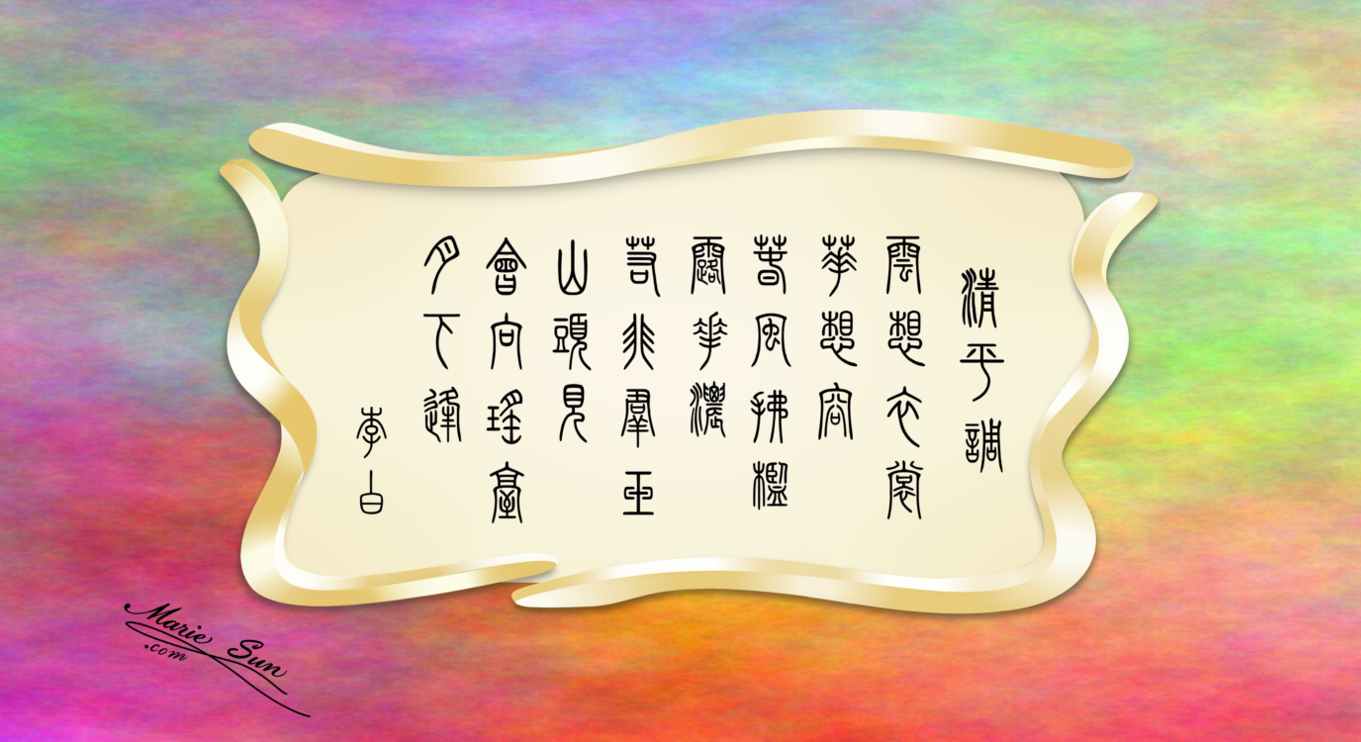

A secondary duty assigned to Li was composing poetry for the emperor. This resulted in the following poem, Qing Ping Ballad, which is a flattering and fawning piece about Yang Guifei and reflects the desires of Tang Ming Huang.

Traditional Chinese

清平調之一 李白

雲想衣裳花想容, 春風拂檻露華濃。

若非群玉山頭見, 會向瑤臺月下逢。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

清 平 调 之 一 李 白

qīng píng diào cí zhī yī lǐ bái

云 想 衣 裳 花 想 容,

yún xiǎng yī shang huā xiǎng róng,

春 风 拂 槛 露 华 浓。

chūn fēng fú kǎn lù huá nóng.

若 非 群 玉 山 头 见,

ruò fēi qún yù shān tóu jiàn,

会 向 瑶 台 月 下 逢。

huì xiàng yáo tái yuè xià féng.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Qing Ping Ballad ( 1 ) Li Bai

A dress imagined by clouds, a look imagined by flowers,

Spring breezes caress the threshold, a lustrous dew showers;

If no meeting occurs at the cluster of Jade Mountain peaks,

Then rendezvous at Jade Pavilion in the moonlight hours.

* * *

This was written at Sinking Incense Pavilion 沈香亭 as Tang Ming Huang and

Yang Guifei wandered among the *peonies -- highly regarded ornamental flowers

in Chinese tradition. At Tang Ming Huang's request, Li Bai wrote three poems -- Qing Ping Ballads I, II and III

on that day. After each poem was completed, the court orchestra would accompany a chanting of it

for the audiences to enjoy. The multi-talented Tang Ming Huang also appreciated music and had a talent for composing, but unfortunately none of his works are extant.

In Qing Ping Ballad I, Li Bai metaphorically describes Yang Guifei's charms and the indulgent pampering she enjoyed from the emperor.

The locations that Li Bai describes in the poem - Jade Mountain and Jade Pavilion - were inhabited by fairies in Chinese folklore,

implying that Yang was a creature from an otherworldly realm. Yang had indeed been living in a fairy tale for 12 years,

indulging in an extremely extravagant life style, courtesy of Tang Ming Huang. What she could not have imagined was

the unexpected and tragic fate that awaited her.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

清 平 调 词 之 一: One of the Qing Ping Ballads 之 一: one of it

云: cloud 想: think, consider, speculate 衣裳: clothes 花: flower 容: looks, appearance, figure, form,

...

...

...

...

... omitted

...

...

...

...

After working for nearly two years at the imperial court,

the incompatibility of Li's personality with court life began to take its toll, as Li was never one

to be bound or driven by secular rules.

Detesting the political machinations, and having his advice ignored by Tang Ming Huang, Li doubted if it was in his best interest to remain at the court.

During this period, the treacherous Prime Minister Li Linfu 李林甫 held tremendous political power, running the country by himself and pushing aside all other capable individuals and potential rivals. All the while, Tang Ming Huang spent most of his time and energy indulging in a lascivious lifestyle with Consort Yang Guefei.

More importantly, it was rumored that the

eunuch Gao Lishi had always felt that being forced to pull off Li Bai's boots was exceedingly humiliating. So he started to badmouth Li Bai to Yang Guifei. He asserted that it was inappropriate for Li Bai to have compared her beauty to that of consort Zhao Yanfei in his second poem "Qing Ping Ballad #2". Zhao was originally of very low birth and status. She was a consort of Emperor Han Chengdi during the Han Dynasty, and was famous for her beauty and slender waist; in contrast, Yang's

great-great-grandfather had been a key official during the previous Sui dynasty, and she had a plump figure, which was the fashion of the Tang Dynasty. Both were consorts doted on by the emperors of their times.

Gao Lishi had been given command of the imperial military forces and had defeated several adversaries in the power struggle for Tang Ming Huang to win the kingdom back for Tang Ming Huang's father. Having established meritorious achievements, he was conferred with the rank of Biaoqi Great General 骠骑大将军 (4th level in military service systems) by Tang Ming Huang, thus holding substantial imperial court military power in addition to political power. He was the favorite eunuch of Tang Ming Huang and even the powerful Prime Minister Li Linfu sometimes publicly flattered him. With such a cast of powerful officials potentially arrayed against him, Li Bai saw the writing on the wall.

In traditional Chinese culture, the most glorious purpose in life was to pursue meritorious honor and fame 功名 (pinyin: gōng míng) in the imperial bureaucratic system. To be able to gain societal recognition in making one's mark on the people and the country was considered of the highest honor. Yet the quality and nature of being a great imperial statesman are quite different from that of being a successful poet, especially a romantic poet. Li finally had an epiphany and abandoned the traditionally defined path to success. Like a fabulous bird, he required an expansive space to fly and soar and not be bound in a golden cage. Hence, his poems began to reflect his desire to leave his bureaucratic mission.

Recognizing that Li Bai was unwilling to continue serving in the court, Tang Ming Huang released him with a handsome severance in the spring of 744.

After a series of farewell parties, Li Bai wrote a moving poem "The Difficult Journey" "难行之旅" expressing his life's ambitions, difficulties he had encountered, and his outlook for the future. And then he said goodbye to the royal court - the center of world power and influence that he had once obsessed about.

Li Bai was characteristically always an optimist;

no setbacks ever seemed to frustrate him, and he could always find a way to see the bright side of life.

Leaving Chang'an and the setting sun behind him in a relaxed and light mood on his

way home, he traveled to and toured Luoyang 洛阳, which was once the capital during

Empress Wu Zetian's

reign. In fact, Louyang, about 200 mi/322 km east of Chang'an, had been the capital for more than six dynasties in China's history before Li Bai's time. Thus, by the Tang dynasty, it was already a famous historical cultural city and peony cultivation center. The poet Du Fu happened to be traveling in the area at that time, too, and so two of the greatest poets in Chinese history met for the first time. Li was 11 years Du's senior and was already an illustrious star poet. Du, on the other hand, had not yet garnered

any fame for himself, and indeed, would not do so in his lifetime. Du, being younger than Li, exhibited the forthrightness, sincerity, and zeal in composing poems that Li had had in his earlier days. All these characteristics drew the two together and helped form a solid friendship right way.

After touring Luoyang and before parting, they scheduled to meet up again in Kaifeng 开封, further east of Luoyang.

view Luoyang via Google,

Baidu, or

wikipedia

.

view Luoyang cultural relic via Baidu.

View a Luoyang cultural relic site - Longmen Grottoes

洛阳龙门石窟

via Baidu or

wikipedia

.

In the autumn, Gao Shi 高适,

a famous border and frontier fortress poet and also Li Bai's friend five years his junior, joined the two of them to tour the Liangsong area 梁宋, which includes present-day Kaifeng 开封 and Shangqiu 商丘 in Henan 河南 Province.

Kaifeng is a beautiful lake city with the Bian River 汴河 running through it. It was one of the busiest trading centers of the Qin, Han, Sui and Tang dynasties. Fifty some years after the end of the Tang, it became the capital of the Northern Song 北宋 Dynasty. The famous painting "Along the (Bian) River During the Qingming Festival" 清明上河圖 elegantly captures one prosperous section of the Bian River in Kaifeng during the Northern Song Dynasty.

Since societal and structural changes generally evolved more slowly in former times than in the modern era, the painting is probably also a fair depiction of bustling daily life in Kaifeng during the High Tang period. One can imagine Li Bai, Du Fu and Gao Shi in the crowd happily crossing the arch bridge, to find a restaurant at which to enjoy gourmet food and fine wine, chattering into the night.

* * *

View daily activities in ancient Kaifeng through the animated version of "Along the River During the Qingming Festival" via YouTube:

River Q. M. - 6 minutes

,

River Q. M. - 12 minutes (with English narration) or

12 minutes (the same as above at different URL),

River Q. M. (1/2) - 7 minutes ,

River Q. M. (2/2) - 7 minutes.

The original painting, about 206 inches by 9.7 inches (528 cm by 24.8 cm) on silk, was orchestrated by

Zhang Zeduan 张择端 (Wikipedia), a famous court painter.

After touring Kaifeng, the three poets traveled to Shangqiu 商丘, a rich historical site.

Two sets of "gold and jade weaved clothes" "金鏤玉衣", dating from around 200 BC to 220 AD, were unearthed in the 20th century from

one of the 18 mausoleums here.

Of course, Li Bai, Du Fu, and Gao Shi did not have the luck to see or even know that there were such treasures hidden just right beneath their feet.

View the mausoleum at Mangdang Mountain in Shangqiu via Google or

view some unearthed items via Baidu.

View the gold and jade weaved clothes from the Liang King Mausoleums in Shangqiu via Google or

Baidu. (There have been more sets of such gold and jade weaved clothing discovered in mausoleums at different locations in China, with at least two of them from Shangqiu.)

After a delightful trip together,

they set off on their separate ways on a clear and refreshing autumn day. Du Fu went north, Gao Shi kept traveling south, and Li Bai continued on his trip home.

According to Du Fu's poems and writings, during the early High Tang period, the cost of living was low and travel was safe, inexpensive, and pleasant.

In the Tang Dynasty, the central government had a very comprehensive postal service system -the Youyi 邮驿 - to deliver mail and goods, as well as provide lodging for Tang officials on their business trips; of course, the most important tasks were to deliver emergency military messages and government documents. At its peak, the system had over 1,600 postal stations, more than 20,000 employees, and covered the entire country, even extending into neighboring countries and regions such as Korea, Japan, Central Asia, India and Southeast Asia. In addition to the Youyi, there was a guifang 柜坊 organization run by private enterprise,

which could issue IOUs similar to modern bank money orders. With these two efficient organizations, Li Bai, who had just received a handsome severance from Tang Ming Huang, could travel light and safe on his way home.

Later in the same year at age 43, Li Bai became romantically involved with a young woman, Zong Shi 宗氏 ("Shi" 氏 is a character placed after a married woman's surname in ancient times. Her giving name was lost to history), who was proficient at literature, was physically attractive, and was also interested in the study of Taoism. Furthermore, she was a long time admirer of Li Bai and came from a prominent family; she was the granddaughter of former Prime Minister Zong Chuke 宗楚客,

who had served in that position on three separate occasions for two Tang emperors.

....

....

....

....

.... omitted

....

....

....

....

....

....

After visiting so many natural wonders, Li Bai finally selected Mt. Lu as his permanent home

due to its beautiful scenery and pleasant weather.

The following poem was created during one of his many trips hiking Mt. Lu.

|

|

|

poem #04

Traditional Chinese

望廬山瀑布 李白

日照香爐生紫煙,

遙看瀑布掛前川。

飛流直下三千尺,

疑是銀河落九天。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

望 庐 山 瀑 布 李 白

wàng lú shān pù bù lǐ bái

日 照 香 炉 生 紫 烟,

rì zhào xiāng lú shēng zǐ yān ,

遥 看 瀑 布 挂 前 川。

yáo kàn pù bù guà qián chuān 。

飞 流 直 下 三 千 尺,

fēi liú zhí xià sān qiān chǐ ,

疑 是 银 河 落 九 天。

yí shì yín hé luò jiǔ tiān 。

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Lookout over the Mount Lu Waterfall Li Bai

Sunlight illuminates the incense peak,

Sparking a purple haze,

I examine a distant waterfall

Hanging before the riverways;

Its flowing waters

Flying straight down three thousand feet,

I wonder -

Has the Milky Way been tumbling from heavenly space?

* * *

....

....

....

....

.... omitted

....

....

....

....

....

....

poem #06

Traditional Chinese

靜夜思 李白

床前明月光,疑是地上霜。

舉頭望明月,低頭思故鄉。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

靜 夜 思 李白

Jìng yè sī lǐ bái

床 前 明 月 光, 疑 是 地 上 霜。

chuáng qián míng yuè guāng, yí shì dì shàng shuāng。

举 头 望 明 月, 低 头 思 故 乡。

jǔ tóu wàng míng yuè, dī tóu sī gù xiāng 。

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Thoughts on a Still Night Li Bai

Before the well lays the bright moonlight,

As if frost blanketing the earth.

My head tilts upwards at the glowing moon;

My head lowers with thoughts of home.

* * *

While on a trip far away from home, Li Bai staring out on a moon-lit night, standing by a well in a courtyard, overcame with a melancholic sense of loneliness

and nostalgia. Such an event inspired him to pen his most famous poem -

"Thoughts on a Still Night". This is one of the most popular poems of all time that almost all Chinese can recite by heart.

Admiring and contemplating a bright, full moon, is a Chinese tradition, especially for a traveler away from home. Chinese believe that when people look at a bright, full moon, while alone on a tranquil night,

their thoughts will naturally wander towards their beloved ones.

Several famous classical verses reflecting this popular conception include:

海上生明月,天涯共此時。-

When the bright moon breaks the surface of the sea,

All under heaven are one at this moment.

明月千里寄相思 -

The bright moon carries lovesickness a thousand miles (to reach a beloved one).

月是故鄉明 -

The moon is brighter over home (implies thinking about and missing beloved ones back in one's hometown.)

The moon represents a direct, shared spiritual connection, as it would be assumed that no matter what the physical distance was separating them, beloved ones would or could all be looking at the exact same moon at the exact same time, sharing the same thoughts of far away beloved ones in their hearts.

Li Bai's "Thoughts on a Still Night" has stirred feelings of homesickness in countless Chinese caught traveling far away from home on silent, moonlit nights, since the Tang Dynasty.

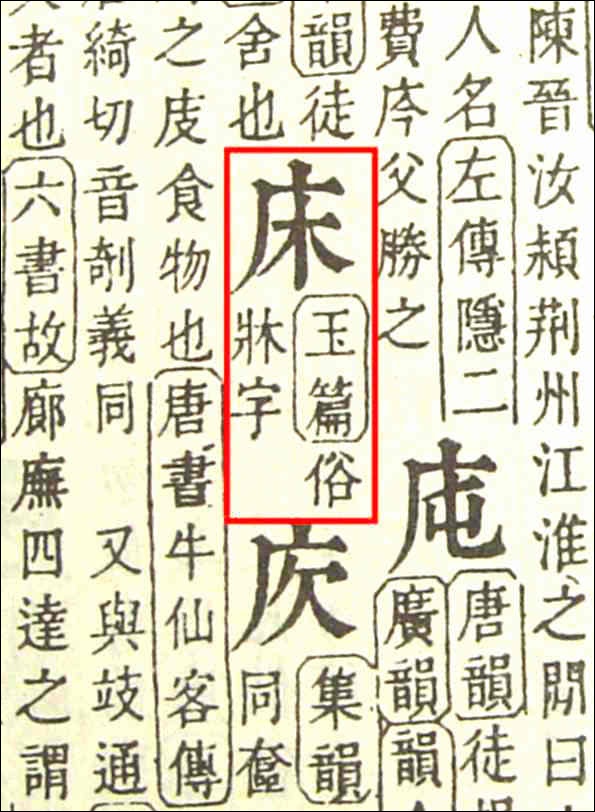

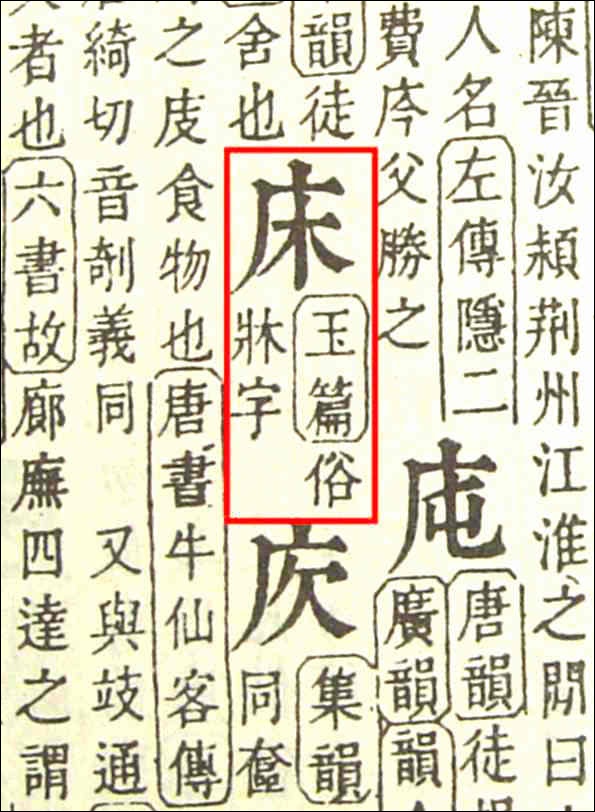

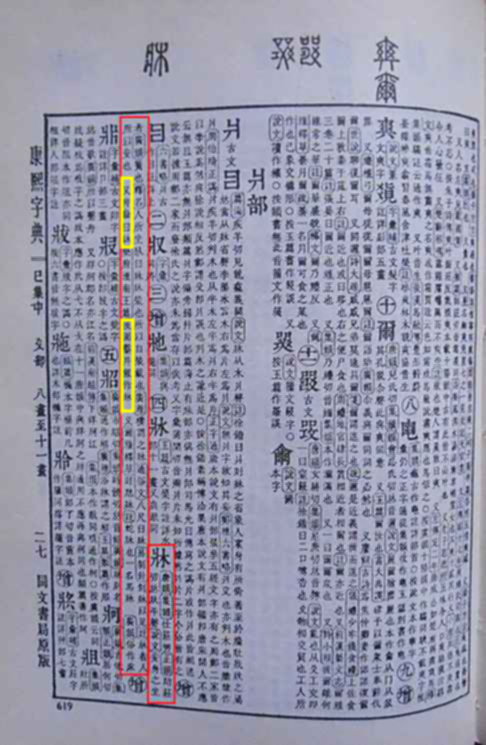

Why is the character "床" (sleeping bed, the structure of ...) translated as "well" in the poem?

While many school children (and translators!) take the Chinese character 床 to mean "bed" in its modern sense, it is more likely to refer to "the structures around a well" in its ancient sense. Ancient Chinese windows were often framed with decorative carvings

and overhead eave-like structures - specifically

to provide shading from sunlight (and prevent break-ins, as they could be shut and locked), but consequently also equally adept at preventing moonlight from entering a room.

It would thus seem unlikely that light could have entered a bed room expansively enough to be mistaken as frost by the bedside.

It is more likely that Li Bai was referring to the platform structure or fence skirting a well, which was an alternate ancient meaning of 床.

Li Bai also wrote another famous poem "Chang Gan Xing" 长干行 employing the character 床 in the sense of a wood structure surrounding a well -

Just starting to wear my hair banged,

I plucked flowers playing by the door.

He came on bamboo hobby-horse to the scene;

Circling the "well"

and pinching plums green.

Neighbors we were in Changgan alley,

Two little ones so trusting and carefree.

妾发初覆额,折花门前剧。

郎骑竹马来,绕

"床" 弄青梅。

同居长干里,两小无嫌猜。

There is no doubt that the "bed"

"床" here never meant a bed for sleeping.

....

....

....

....

.... omitted

....

....

....

....

....

....

View the following images:

1. Chinese calligraphy 靜夜思书法:

view thru Google or

Yahoo.

2. View architectural window style in Tang Dynasty

thru

Google or

Baidu.

3. View architectural window style in ancient China thru

Google or

Baidu.

4. View a well with a surrounding platform "bed"

thru Google

or

Yahoo.

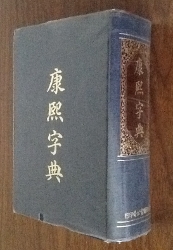

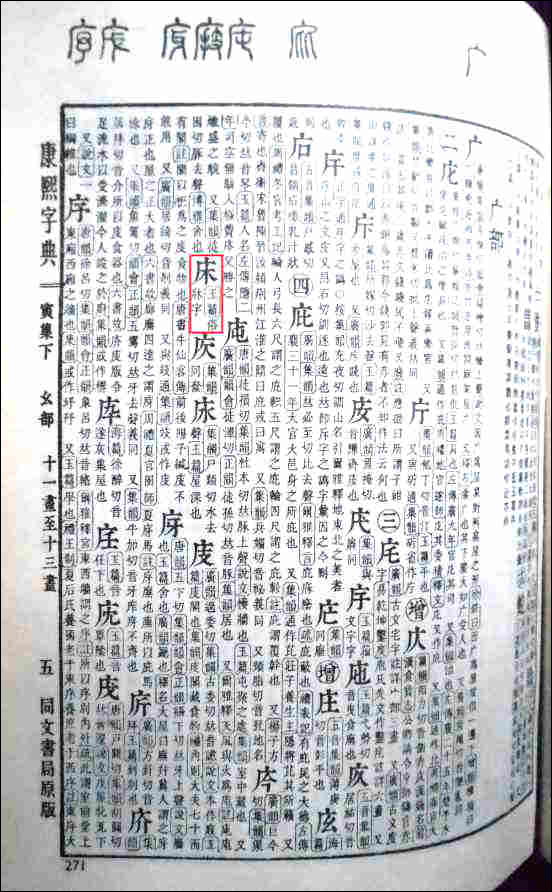

5.

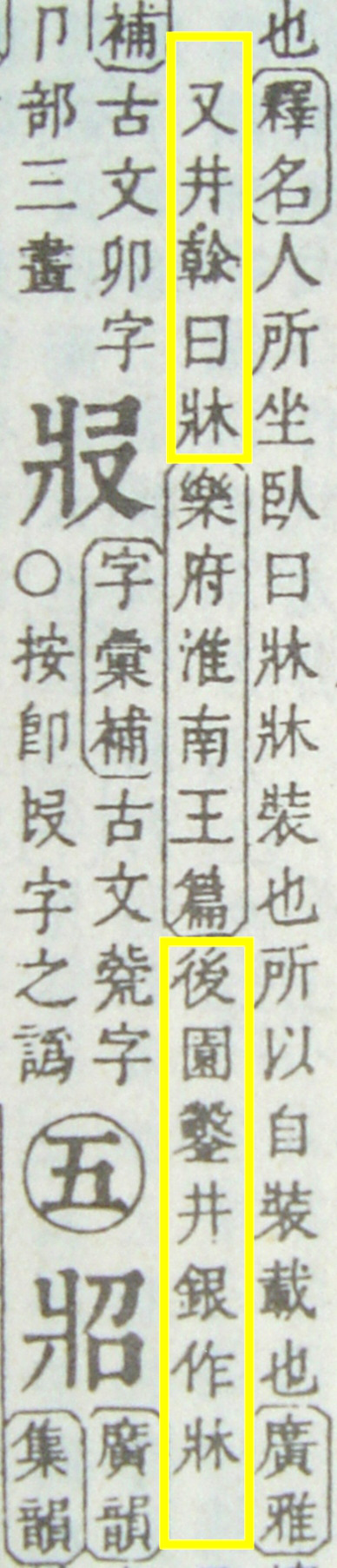

Search results from the

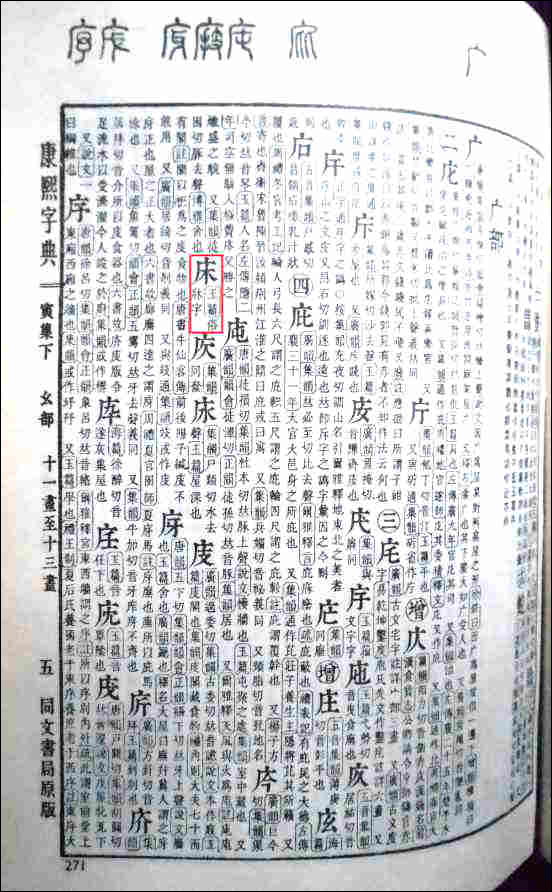

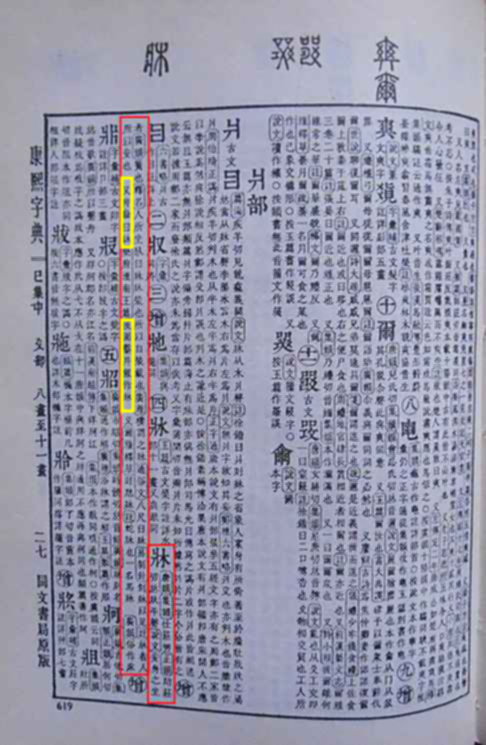

Kangxi Dictionary 康熙字典 (Wikipedia)

about "bed" "床":

"床" means both:

(1) a bed for sleeping or,

(2) a structure around a well.

The character for "bed" 床 can also be written as 牀.

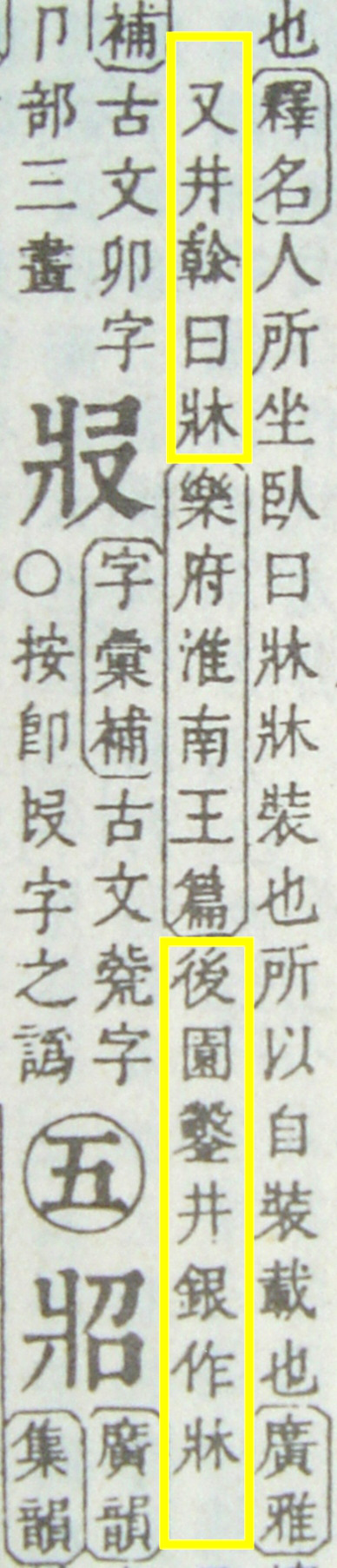

"又井榦曰牀" - "Again, the wooden structure around a well is called a bed".

"後園鑿井銀作牀" - "To dig a well in the back garden and fence it with stakes or other structures."

poem #07

Traditional Chinese

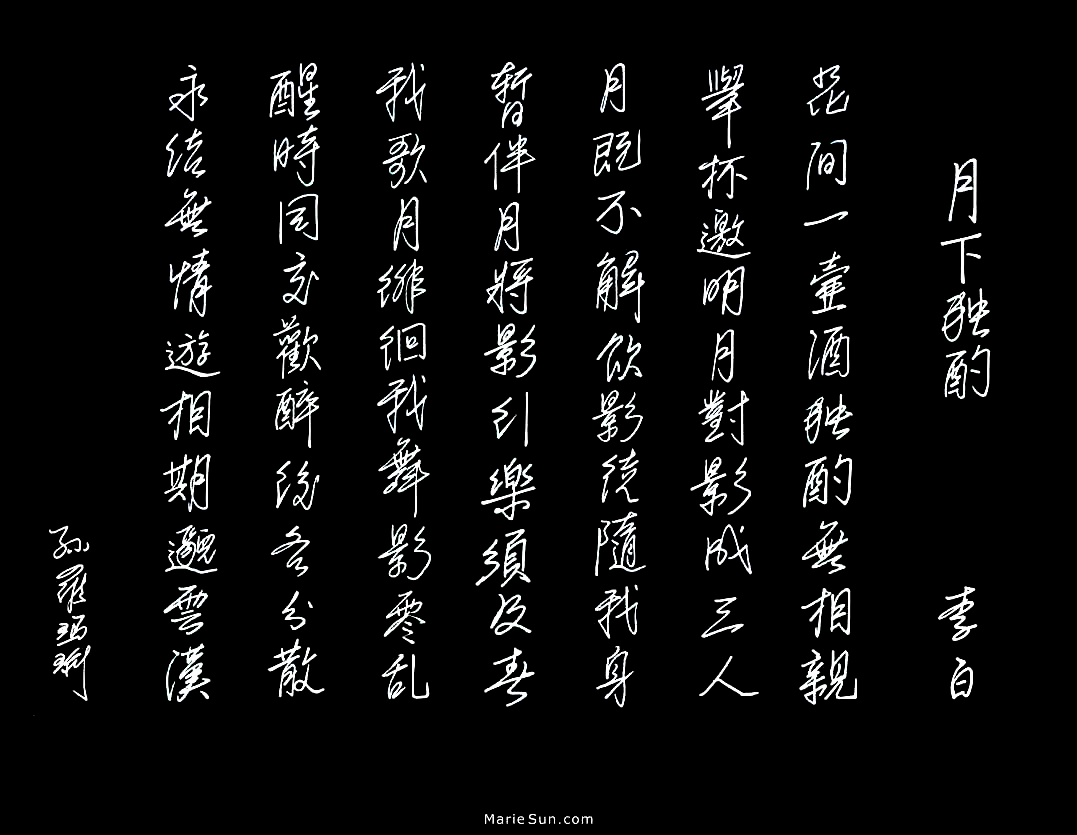

月下独酌 李白

花間一壺酒,独酌無相親;

舉杯邀明月,對影成三人。

月既不解飲,影徒隨我身;

暫伴月將影,行樂須及春。

我歌月徘徊,我舞影零亂;

醒時同交歡,醉后各分散。

永結無情遊,相期邈雲漢。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

月 下 独 酌 李 白

yuè xià dú zhuó lǐ bái

花 间 一 壶 酒, 独 酌 无 相 亲;

huā jiān yī hú jiǔ, dú zhuó wú xiāng qīn,

举 杯 邀 明 月, 对 影 成 三 人。

jǔ bēi yāo míng yuè,duì yǐng chéng sān rén.

月 既 不 解 饮, 影 徒 随 我 身;

yuè jì bù jiě yǐn,yǐng tú suí wǒ shēn,

暂 伴 月 将 影, 行 乐 须 及 春。

zàn bàn yuè jiāng yǐng,xíng lè xū jí chūn

我 歌 月 徘 徊, 我 舞 影 零 乱;

wǒ gē yuè pái huái, wǒ wǔ yǐng líng luàn

醒 时 同 交 欢, 醉 后 各 分 散。

xǐng shí tóng jiāo huān, zuì hòu gè fēn sàn

永 结 无 情 游, 相 期 邈 云 汉。

yǒng jié wú qíng yóu, xiāng qī miǎo yún hàn

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Drinking Alone by Moonlight Li Bai

A jug of wine amidst the flowers,

I drink alone with no soul around.

I raise my wine cup to the moon and invite her down;

Now we are three with my shadow.

The moon, she does not drink,

And my shadow follows my every move;

But for the moment,

The moon is my partner and I hang with my shadow.

To enjoy life is to take advantage of youth.

I sing, the moon hovers all around;

I dance, the shadow follows in a messy stumble.

Lucid, we enjoy each other knowingly;

In drunken sleep, we go our separate ways.

Bound to forever travel carefree,

We shall meet again in cosmic paradise.

* * *

Li Bai was a wine lover. Wine seemed to be catalyst that could ignite his poetic prowess with such speed

that he could reportedly pen a poem in a matter of seconds after a few drinks. Thus, he was accorded the name of Jiouxian 酒仙, literally, "wine immortal."

As a wine connoisseur he wrote numerous poems on the subject. "Drinking Alone by Moonlight" is one of the most famous among all

"wine poems" written by East Asian poets through the ages. Induced by just a jug of wine, Li Bai dances into a fanciful world; and by the magic of his pen brush, he brings the reader along with him into his fantastical reverie.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

...

...

...

... omitted

...

...

...

...

#11 Longing in Spring 春思

Traditional Chinese

春思 李白

燕草如碧絲, 秦桑低綠枝;

當君懷歸日, 是妾斷腸時。

春風不相識, 何事入羅幃?

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

春 思 李 白

chūn sī lǐ bái

燕 草 如 碧 丝, 秦 桑 低 绿 枝;

yàn cǎo rú bì sī, qín sāng dī lǜ zhī;

当 君 怀 归 日, 是 妾 断 肠 时。

dāng jūn huái guī rì, shì qiè duàn cháng shí.

春 风 不 相 识, 何 事 入 罗 帏?

chūn fēng bù xiāng shí, hé shì rù luō wéi

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Longing in Spring Li Bai

Yan grasses like strands of emerald jade silk,

Qin mulberries weighing down branches green.

The day when your sire thinks of coming home,

Is when this lady's heart will be dying in tortured waiting.

O! Spring breeze - I dare not know you,

Why slip into the silk curtain surrounding my bed?

* * *

Li Bai uses symbolic imagery to delicately portray the

mood of a young woman

whose amorous feelings are aroused by the onset of spring,

but who has no way to satisfy them, except through a deep yearning for

her husband stationed far away. Yet a

gently, titillating spring breeze blows into her bedroom to

tease and arouse her even more.

Li Bai could be said to have had an intricate and precise understanding of women.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

春思: longing in spring

燕: Yan, located in present-day northern Hebei 河北 Province and western Liaoling 辽宁 Province -- the frontier in the Tang Dynasty. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers were stationed there, including, no doubt, the husband of the young lady in the poem.

草: grass, lawn, straw 如: as, as if, such as , 碧丝: green jade, bluish green, blue, jade, blush green silk, blue silk

秦: Qin, located in present-day Shanxi 陕西 Province. During the Tang Dynasty, a great many soldiers were drafted from this area and sent to

the bordering Yan area to guard the country.

桑: mulberry 低: low, beneath, to lower (one's head), to let droop, to hang down, to incline 绿枝: green branch

当: when, to be, to act as, during 君: you (a respectful form of address towards a man), monarch, lord, gentleman, ruler 怀: to think of, mind 归日: return day

是: is, are, am, yes, to be 妾: a polite term used by a woman in olden days to refer to herself when speaking to her husband, concubine

断肠: heartbroken. However, in the poem, it may imply to be heart-pounding, like butterflies in the stomach 时: time, o'clock

春风: spring breeze, good education, happy smile, sexual intercourse 不: no, not 相识: acquaintance, to get to know each other

何: what, how, why, which 事: matter, thing 入: to enter, to go into, to join 罗帏: curtain of thin silk (around the bed), women's apartment, tent

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Locations that the young wife's husband might have been deployed to and stationed:

(1). The Great Wall garrison bases in Hebei Province 河北长城戍地:

View thru Google or

Baidu.

or

(2). The Great Wall garrison bases in Liaoning Province 辽宁长城戍地:

View thru Google,

Baidu or

Yahoo.

2. Mulberry 桑 (the mulberry leaves are the sole food source for the silkworm.):

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

3. Chinese calligraphy 春思书法:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

...

...

...

...

...

...

In December 755, the An Lushan Rebellion 安祿山之乱 broke out in Youzhou. Not long afterwards, the whole empire was thrown into turmoil. (There is an entire chapter dealing with An Lushan and the antecedents and consequences of the rebellion.)

Seven months later, An Lushan overcame a key military fortress - the Tong Pass,

and Emperor Tang Ming Huang hurriedly fled towards Chengdu, Sichuan Province

成都, 四川省, while

the Crown Prince Li Heng 李亨 took refuge in Lingwu, Ningxia Province 灵武, 宁夏省 and soon declared himself the new Tang emperor. After hearing news of the declaration, Prince Li Ling 李璘, the 16th son of Tang Ming Huang,

rose up in Jiang Ling 江陵,

present-day Jingzhou city, Hubei Province 荆州市, 湖北省 against his brother, in the name of protecting his emperor father's sovereignty.

Appreciating Li Bai's fame and his literary talent, Li Ling continually sent messengers to Mt. Lu in order to

cajole Li Bai into accepting a position as his key propaganda advisor and secretary.

Li Bai's poems, such as "The Song of Youth" "少年行", "The Song of Knights" "侠客行", as well as many others, reflected his life attitude, which had long been of the chivalrous sort. Thus, after Li Ling's repeated and earnest invites, Li Bai, in spite of his wife's attempts as dissuasion, agreed to join with Li Ling in 756. Proceeding with a knight-errant spirit, he hoped to be able to contribute and do something for the good of the country,

The next year, the new Emperor Li Heng defeated Li Ling, capturing and executing him. Li Bai was likewise jailed and awaited his fate. Upon hearing the shocking news, Du Fu wrote several poems to Li Bai to express his deep concerns and worries. During Du Fu's lifetime, he wrote many poems and letters to Li Bai, as the latter's talent, charisma, and the attitude towards life deeply attracted Du Fu.

During this critical period, Li Bai's wife, Zong Shi, sought help from all corners to mitigate

a finding of treason, which would have almost certainly resulted in a death sentence.

...

...

...

... omitted

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

... omitted

...

...

...

About Li Bai's Life Journey in Details

(1).

Li Bai's Birth and Childhood

Li Bai (701 - 762; lived mostly in the High Tang period and only a few years into the beginning of Mid Tang period), the most famous romantic poet in Chinese history, penned numerous masterpieces that are still memorized and chanted by Chinese of all ages today. He went by many names; his most popular and well-known title being Shi Xian 诗仙 - "the Poet Immortal" or "the Poet Transcendent”. His name has also been romanticized as Li Po or Li Bo. Thirty-four of Li Bai's poems are included

in the popular anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems,"

second only to Du Fu's thirty-nine poems.

Li Bai's ancestors were from Longxi, Chengji

陇西, 成纪, in present-day northern Qinan county, Gansu Province 秦安县北, 甘肃省. They were banished to Tiaozhi 条枝 in the Western Regions 西域, today's Central Asia, during the Sui Dynasty by the Sui ruler.

As for Li Bai's birth place, according to Guo Moruo 郭沫若, a historian and ancient writing scholar, Li Bai's ancestors moved from Tiaozhi to a prosperous silk trading city Suiye 碎叶, also in Central Asia, within the Ansi Protectorate 安西都护府, and Li Bai was born over there. Suiye was

also known as Suyab, once a flourishing trading city on the Silk Road and now an archaeological

site in modern day Ak-Beshim, Kyrgyzstan.

View present-day Ak-Beshim (Suiye) in

Kyrgyzstan

thru Google or

Yahoo.

View details regarding

Ak-Beshim:

Wikipedia.

Li Bai's father, Li Ke 李客, was probably a very successful merchant, since the family was installed in one of the thriving commercial centers of the empire. In 705, Li's father moved the family back to China and settled down in Jiangyou, Sichuan Province 江油, 四川省. (

View Jiangyou thru Google or

Baidu.)

(Jiangyou is bordered on the northeast side by Mianyang City 绵阳市 - today's "Silicon Valley" in China.)

Speculated birthplace of Li Bai- Suiye (the blue drop shape) and his second "hometown" (the green drop shape):

(Source: Google Map)

The young Li Bai read extensively, devouring not just Confucian classics, but

also various tracts on astrological and metaphysical subjects, including the Chinese classic text -

Tao Te Jing/Dao De Jing 道德经 (Wikipedia).

He was also skilled in swordsmanship.

His place of birth, his tall girth, and his angular

facial features, suggested that he was possibly of mixed race. It was said that he was conversant in at least one foreign language due to his background and upbringing.

In 725 at age 24, Li Bai left his second hometown, Jianyou, to explore the world. Being young, ambitious,

and without

financial constraint, he embarked on a knight-errant-like journey. Heading east down the Yangtze River, he explored all the most popular cities and interesting spots along the Yangtze River including

the Three Gorges, the largest lake Dongting Lake 洞庭湖, the famous Mount Lu 庐山,

all the way to Jingling 金陵 (present-day Nanjing 南京, in Jiangsu 江苏 Province).

While passing through the Jingmen Gorge, he left behind a beautiful poem "Bid Farewell at Jingmen" 荆门送别.

Along the way he met and befriended various poets and social elites, including Meng Haoran, who Li Bai had long admired.

Li Bai wrote several poems in admiration and praise of Meng, including the very popular one - Seeing Meng Haoran off at Yellow Crane Tower 黄鹤楼送孟浩然之广陵.

While touring Hubei, Li Bai was introduced by friends to the family of the former Prime Minister Xu Yushi 许圉师.

Li, at age 26, was young, handsome, and well-built. He excelled at both swordsmanship and literature, and had about him a chivalrous and gentlemanly demeanor. A budding poet, he was well-received by Xu's family and eventually married the former Prime Minister's granddaughter, Xu Ziyan

许紫烟. The couple settled down at Peach-flower Rock, near Li's in-laws in present-day

Anlu, Hubei Province 安陸, 湖北省.

Although Li Bai would travel from time to time or take short mountain sabbaticals (to enhance study and reflection) for the purposes of obtaining a position in the imperial court, the couple led a content married life with little financial burden, with Xu Ziyian bearing a daughter, Li Pingyang 李平阳, and a son, Li Boqin 李伯禽.

While away from home,

Li Bai wrote many letters and poems to his wife

to express his loneliness and longings, some of which were very witty and humorous.

The blessed marriage lasted for 12 years. In 740, Xu Ziyian passed away. Since several of Li's close relatives lived in Renchen

任城, located on the south side of present-day Jiling city, Shandong Province 济宁市, 山東省, Li Bai moved his family there. This was not far from Lu county, where Confucius' hometown is located.

After settling down at Renchen, Li Bai managed to spend some time living in seclusion with five other hermits on Mt. Culai

徂徕山 (

view Mt. Culai thru Google or

Baidu).

They settled by a scenic brook in a bamboo forest, and hence the six of them earned a collective name - "The Six Hermits of Leisure of the Bamboo Brook" 竹溪六逸. Needless to say, Li Bai spiritually enjoyed his time there, taking in the surrounding mountain scenery, drinking wine, enjoying tea, playing music, practicing his fencing, and especially chanting poems together with his like-minded companions. While living on Culai Mountain, Li Bai continued to maintain contact with the local intelligentsia and gentry through letters and visits in order to get his name heard. This was the fashion during Tang Dynasty for ambitious scholars to obtain a central government appointment in the imperial court. Li Bai lived on Culai Mountain intermittently on three separate occasions.

Mt. Culai, the sister mountain of Mt. Tai 泰山, lies about 12.5 mi/20 km

to the southeast of Mount Tai. In Chinese feudal tradition, emperors would come to this area atop Mt. Tai and hold Heaven-and-Earth worship ceremonies 祭天祭地, also called fēngchán 封禅, during prosperous periods to pay gratitude to Heaven and Earth. Another main purpose was to justify and reify their "superpower" and authority over their people. After the ceremony, the emperors would also often stop at nearby Qufu 曲阜 in Lu county, the birthplace of Confucius, to hold a ceremony honoring him 祭孔大典.

Early in the Han Dynasty, Emperor Han Wudi 汉武帝 had paid three visits to the area, performing the aforementioned ceremonies. Several Tang emperors did so as well. Emperor Tang Ming Huang performed the ceremonies for the first and only time in 725, the year Li Bai was just stepping out of Sichuan to explore the world. While holding ceremony in Lu county, Tang Ming Huang composed a poem called "Passing through Zou Lu and offering a sacrifice to Confucius with a sigh" "经邹鲁祭孔子而叹之". This is the only poem by the emperor, himself, that is included in the anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems".

Living on nearby Culai Mountain and cultivating a reputation as a learned, self-sufficient, capable man, Li Bai provided himself the chance of being recognized and introduced to the Tang emperor during these ceremonies and would have had the opportunity to be possibly "fast track" into the imperial service.

Before his wife passed away, Li had lived in seclusion on several other mountains as well. One of these was

Zhongnan Mountain 終南山 (

view the mountain, hermits and monks thru Google or

Baidu,)

about 10 miles south of the Tang capital of Chang'an. He lived there around age 29 for less than a year. During the early Tang, the famous scholar hermit Lu Cangyong 卢藏用 lived on this same mountain and was called in by

Empress Wu Zetian 武则天

to work for the central government. Lu began at the position of a remonstrative official - Zuoshiyi 左拾遗 (

duties of remonstrative officials in the Tang Dynasty

and

rank schedule of the imperial civil service system), working his way up quickly to the Shangshu-Youcheng 尚书右丞 level, i.e., almost to

the position of prime minister. This is the origin of the Chinese idiom "Zhongnan Fast Track" "终南捷径". Li Bai, however, did not meet with such fortune on Zhongnan Mountain.

In 742, Hè Zhizhang 賀知章, about 83 years old at the time and a leading light of literature and high-level imperial official, read Li's poems, marveled at his literary talent, and praised Li Bai as the "Transcendent Dismissed from Heaven" or

"Immortal Exiled from Heaven"

"謫仙人". From this point forward the acclamation "Li Bai, the 'Transcendent Dismissed from Heaven' " began to spread throughout the empire. And the two cemented the bond of a lifelong friendship.

(2). Li Bai's Ambitious Dream Starts to Bud - An Audience with the Tang Emperor

In the late summer of the same year, Emperor Tang Ming Huang, who had caught wind of Li Bai's reputation, summoned him to the the capital Chang'an for an audience. From Li Bai's home to Chang'an was nearly a distance of 600 mi/965 km, as the crow flies. Li did not arrive until the autumn.

Emperor Tang Ming Huang, an expert on military strategy who also excelled at literature, greeted Li Bai at the Grand Palace in person. During the banquet, Li's personality, wit, and political views fascinated Tang Ming Huang. The emperor even personally seasoned the soup for Li Bai.

The next year, Li Bai was assigned a

Hanlin 翰林

position at the Hanlin Academy

翰林学院 within the imperial court and appointed the state Grand Secretary.

As a result of the emperor's favor, Li was never required to take the imperial examination to attain the title of jinshi, a usual prerequisite for selection and assignment to a Hanlin position. Indeed, Li Bai never attempted to take the

imperial examination at all.

It was rumored that this was because his ancestors had been banished to Central Asia for some kind of crime. The norm at the time was that offspring of criminals were automatically disqualified from taking the exam, but his ancestors were banished in the Sui Dynasty (581 - 618)

and the Sui was overthrown by the Tang in 618, some 80 years before Li Bai was born!

Being from a merchant family also would have disqualified him from taking the imperial examination, though. This policy was adopted most likely to prevent collusion between government employees and businessmen. But in reality, this policy was never consistently implemented. Highly wealthy merchants could always circumvent the rules and secure important government positions. One such example was Wu Shiyue 武士彠, a successful lumber businessman with good connections to the Tang royal family, who secured several important government positions early during the dynasty and indirectly helped his daughter -

Wu Zetian 武则天

“usurp” the throne. (There is an entire chapter devoted to Wu Zetian -- another Tang poetry promoter and grandmother of Tang Ming Huang -- in "Tang Poems" volume 2.)

This regulation was eventually repealed by the following Song (Sung) Dynasty 宋朝, and almost all classes of males (and only males) were thereafter permitted to take the exam. In any event, during Li Bai's lifetime he often broke from convention and followed his own path.

In the beginning, Li led a fairly pleasant life at court. The famous verse "Guifei grinding ink, Lishi pulling off boots" "贵妃磨墨, 力士脱靴" describes this period. It depicts Yang Guifei 楊貴妃, Tang Ming Huang's most adored consort, grinding Chinese black inksticks into ink for Li to pen down a poem, while Gao Lishi 高力士, Tang Ming Huang's favorite

eunuch 宦官,

(and the most politically powerful figure in the palace), assists in pulling off Li's snow stained boots under Tang Ming Huang's request. All to facilitate Li’s comfort and creative genius. It was also suggested that whenever Li Bai published a new poem, there would be a run on paper in Chang'an, sending the price soaring, with everyone rushing out to obtain copies of his new work.

Li's main duty was to handle secretarial works and record tasks for Tang Ming Huang, which included accompanying Tang Ming Huang to important ceremonies and festivities and documenting them. Tang Ming Huang probably intended that through Li's exquisite writing, the records of his reign would be of particular interest to future historians and scholars.

A secondary duty assigned to Li was composing poetry for the emperor. This resulted in the poem,

Qingping Song (1) 清平调词之一

which is a flattering and fawning piece about Yang Guifei and reflects the desires of Tang Ming Huang.

After working for nearly two years at the imperial court,

the incompatibility of Li's personality with court life began to take its toll, as Li was never one

to be bound or driven by secular rules.

Detesting the political machinations, Li doubted if it was in his best interest to remain at the court.

During this period, the treacherous Prime Minister Li Linfu 李林甫 held tremendous political power, running the country by himself and pushing aside all other capable individuals and potential rivals. All the while, Tang Ming Huang spent most of his time and energy indulging in a lascivious lifestyle with Consort Yang Guefei.

More importantly, it was rumored that the

eunuch

Gao Lishi had always felt that being forced to pull off Li Bai's boots was exceedingly humiliating. So he started to badmouth Li Bai to Yang Guifei. He asserted that it was inappropriate for Li Bai to have compared her beauty to that of consort Zhao Yanfei in his second poem "Qing Ping Ballad #2". Zhao was originally of very low birth and status. She was a consort of Emperor Han Chengdi during the Han Dynasty, and was famous for her beauty and slender waist; in contrast, Yang's

great-great-grandfather had been a key official during the previous Sui dynasty, and she had a plump figure, which was the fashion of the Tang Dynasty. Both were consorts doted on by the emperors of their times.

Gao Lishi had been given command of the imperial military forces and had defeated several adversaries in the power struggle for Tang Ming Huang to win the kingdom back for Tang Ming Huang's father. Having established meritorious achievements, he was conferred with the rank of Biaoqi Great General 骠骑大将军 (4th level in military service systems) by Tang Ming Huang, thus holding substantial imperial court military power in addition to political power. He was the favorite eunuch of Tang Ming Huang and even the powerful Prime Minister Li Linfu sometimes publicly flattered him. With such a cast of powerful officials potentially arrayed against him, Li Bai saw the writing on the wall.

...

...

... omitted

...

#17 Writings of a Night Lodging 旅夜书怀

Traditional Chinese

旅夜書懷 杜甫

細草微風岸,危檣獨夜舟。

星垂平野闊,月湧大江流。

名豈文章著?官因老病休。

飄飄何所似?天地一沙鷗。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

旅夜书怀 杜甫

Lǚ yè shū huái dù fu

细草微风岸,危樯独夜舟。

xì cǎo wéi fēng àn, wēi qiáng dú yè zhōu.

星垂平野阔,月涌大江流。

Xīng chuí píng yě kuò, yuè yǒng dà jiāng liú.

名岂文章著?官因老病休。

Míng qǐ wén zhāng zhe, guān yīn lǎo bìng xiū.

飘飘何所似?天地一沙鸥。

Piāo piāo hé suǒ sì? Tiān dì yī shā'ōu.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Traveling Thoughts at Night Du Fu

A soft breeze stroking fine grass on the shore;

A tall mast soaring alone in the night.

Over the vast plain, do the stars descend,

Out of the flowing river, does the moon rise.

Could a lifetime of writing ever bring glory?

Retired I am, sickly and aged, my plight.

Drifting, drifting, what am I?

A lone seagull floating between earth and sky.

* * *

Around the year of 766, Du Fu, his wife, and their four children, had moved onto a simple and crude boat along the Yangtze River starting their drifting life. Writings of a Night Lodging 旅夜书怀 was written during that difficult period.

This poem ironically employs the majestic, natural beauty of a night scene to accentuate the cruel indifference of fate. In the vastness of the night, the author reflects upon his chronic illness in old age, the aimless drifting of his life, and the unmoored tumult of his desolate mood. The scene evokes an emotional response enough to fill the eyes of the reader with tears of sympathy for this talented poet.

...

...

...

Hè Zhizhang 贺知章

Hè Zhizhang (659 - 744; lived in the Early and High Tang periods) was born in Xiaoshan, Zhejiang Province 萧山, 浙江省.

Only one of his well-known works "Coming Home" "回乡偶韦" is included in the

popular anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems."

The poem actually has eight verses, but since only the first four verses are popularly recited, only this part is reproduced below.

His other very popular poem is called "Chanting Willow" "咏柳".

As with many others of his time, he, too sought his fortune through the

imperial examination system, passing the exam and entering into the civil service during Empress Wu Zetian's reign. Hè's career was long and smooth-sailing.

In 710 at age 51, during Emperor Li Xian's reign (Empress Wu Zetian's third son) he was promoted to the honorable position of a

Hanlin Scholar 翰林学士.

He had a bold and unconstrained personality.

After reading Li Bai's poems, he was

highly impressed and praised Li Bai as

"An Immortal Exiled from Heaven!" "天上谪仙人也!" Hence, people began referring to Li Bai as the "Poet Immortal"

"诗仙" (pinyin: shī xian).

In 742, Hè (about 83 years old and a leading figure in the literary world by that time), met Li Bai for the first time. Appreciating Li Bai's talent, Hè made Li a close friend, even though he was 41 years Li Bai's senior. Both were fond of bottle and were listed in Du Fu's work

"Eight Immortals of the Wine Cup" "饮中八仙".

He was not only a leading figure in the literary world but also well-known for his cursive script 草书

and clerical script 隶书 calligraphy.

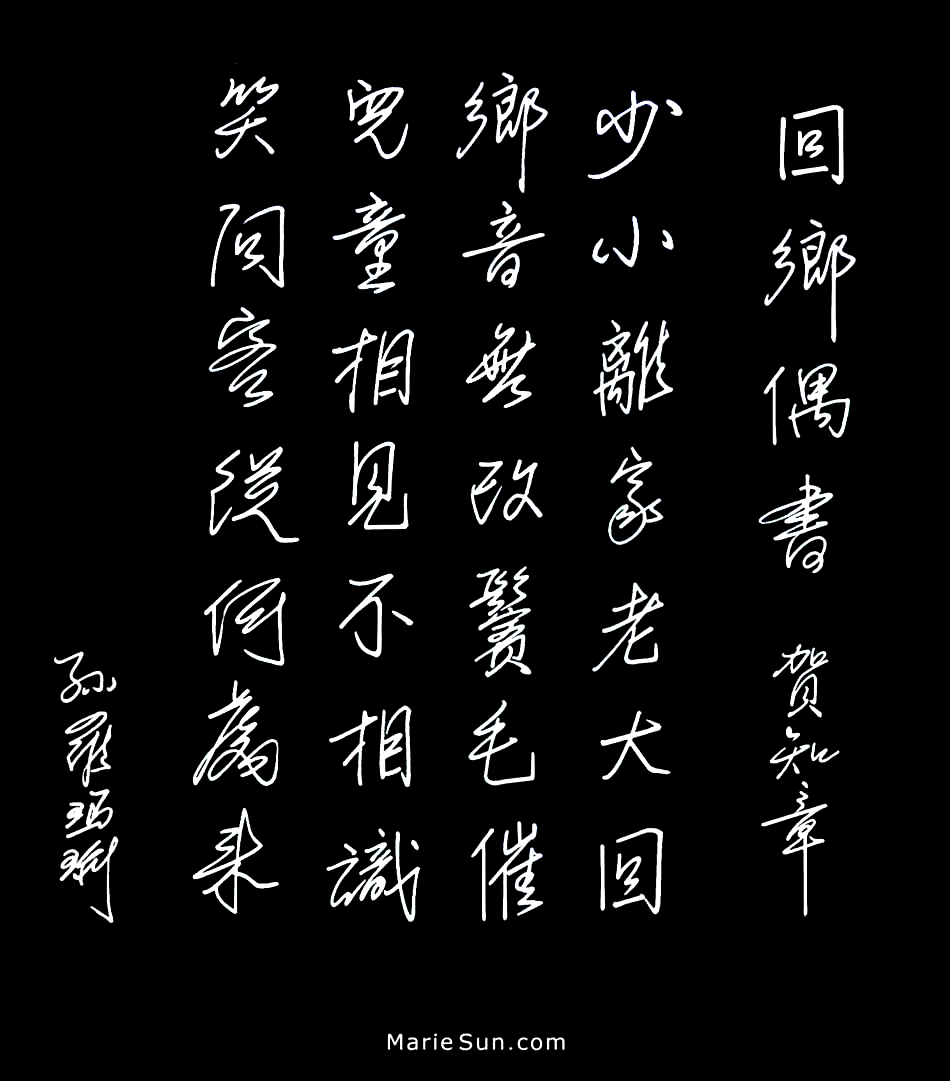

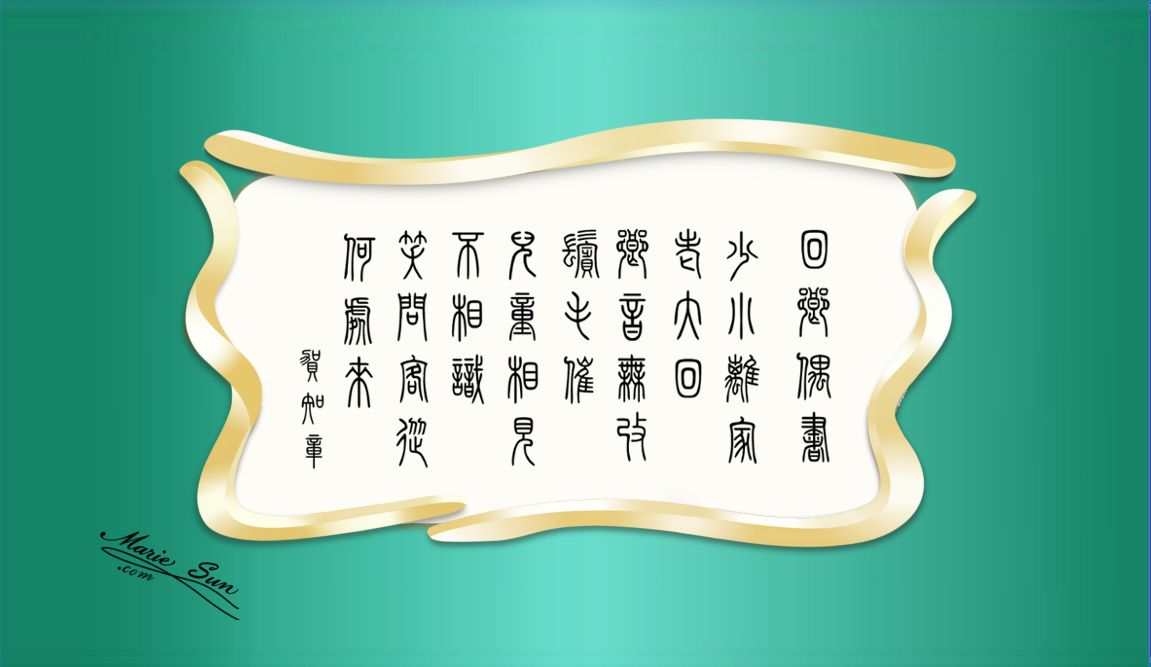

#19 Random Musings on a Homecoming 回乡偶书

Traditional Chinese

回鄉偶書 賀知章

少小離家老大回,

鄉音無改鬢毛催。

兒童相見不相識,

笑問客從何處來?

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

回 乡 偶 书 贺知章

Huí xiāng ǒu shū hè zhī zhāng

少 小 离 家 老 大 回,

shào xiǎo lí jiā lǎo dà huí,

乡 音 无 改 鬓 毛 催。

xiāng yīn wú gǎi bìn máo cuī.

儿 童 相 见 不 相 识,

Ér tóng xiāng jiàn bù xiāng shì,

笑 问 客 从 何 处 来?

xiào wèn kè cóng Hè chù lái?

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Random Musings on a Homecoming

Hè Zhizhang

I left home a young buck and returned an old man.

My accent's the same,

but sideburns silver have run.

They greet me,

the children,

but know not who I am.

Smiling they ask me, "you come to us,

dear sir,

from which faraway land?"

* * *

Hè outlasted 4 emperors through his long career, and there are no records showing he was ever banished, which was a somewhat unusual achievement for any imperial official, especially outspoken ones.

After a lifetime of service with the imperial court, Hè retired at a very late age.

Thus, he returned to his hometown only after some 50 years.

"Random Musings on a Homecoming" describes his experience after having been away for so many years. Upon arriving, a group of cheerful children greet him as an old "stranger".

Time has passed and things have changed, including himself. There is an undercurrent of sentimental regret for being away so long mixed with the joyful emotion of finally coming home.

This is a poem universally appreciated by all Chinese, for whom home and family are so important.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

回: return, come back 乡: home village or town, native place, country or countryside

偶: accidental, pair, mate 书: book, letter, document, to write

少小: young, 离家: left hometown, left home, 老大: old age, eldest child in a family, leader of a group, boss, leader of a criminal gang 回: return, turn around, a time

乡音: local accent, accent of one's native place 无改: no change 鬓毛: hair on the temples 催: to urge, to press, to hasten, to prompt , to rush. Some versions of the poem use the word 衰 (weak and old) instead of 催. A popular Chinese phrase with 催 is "Time has pushed one into old age with gray hair mercilessly running down the temples" "歲月催人老, 无情白发生."

儿童: child, kid 相见: to see each other, to meet in person 不: not, no, negative prefix 相识: to get to know each other, acquaintance

笑: smile, laugh 问: to ask 客: guest, customer, visitor 从: from 何处: where 来: to come

View the following images related to the poem or the poet:

Chinese calligraphy 回乡偶书书法:

view thru Google

or

Baidu.

Hè Zhizhang "cursive Xiaojin" calligraphy 贺知章 "草书孝经" 书法:

view thru Google

or

Yahoo.

Wang Han 王翰

Wang Han (687 - 726; lived during the Early and High Tang periods) was born into an affluent family in present-day Taiyuan,

Shanxi Province 太原, 山西省.

In 710 at age 23, Wan Han passed the

imperial examination,

obtaining a jinshi degree-title and began his short-lived civil service career. In 721, Wang Han's close associate Zhang Yuè 张说 (说 usually pronounced as shuō, meaning "to say", but if it is used as a name, pronounced as yuè), who excelled at both politics and military affairs, as well as poetry, rose to serve as prime minister for the third time, and aided Wang Han in his career.

Wang had a vigorous and unrestrained personality like a runaway horse. His poems paint deeply affecting and emotionally provocative scenes that move the reader's thoughts and feelings.

Thirteen of his poems are extant, but only his most famous

"Beyond the Border" is in the popular anthology

"Three Hundred Tang Poems."

Coming from a wealthy family, Wang Han led a luxurious and decadent lifestyle - breeding thoroughbred horses and

maintaining a household harem. His self-promotion and self-indulgent noble airs resulted in his being demoted upon Zhang Yue's

retirement. After being demoted, he continued to indulge in a lascivious lifestyle which contributed to his being banished and passing away at age 39 while on his way into exile.

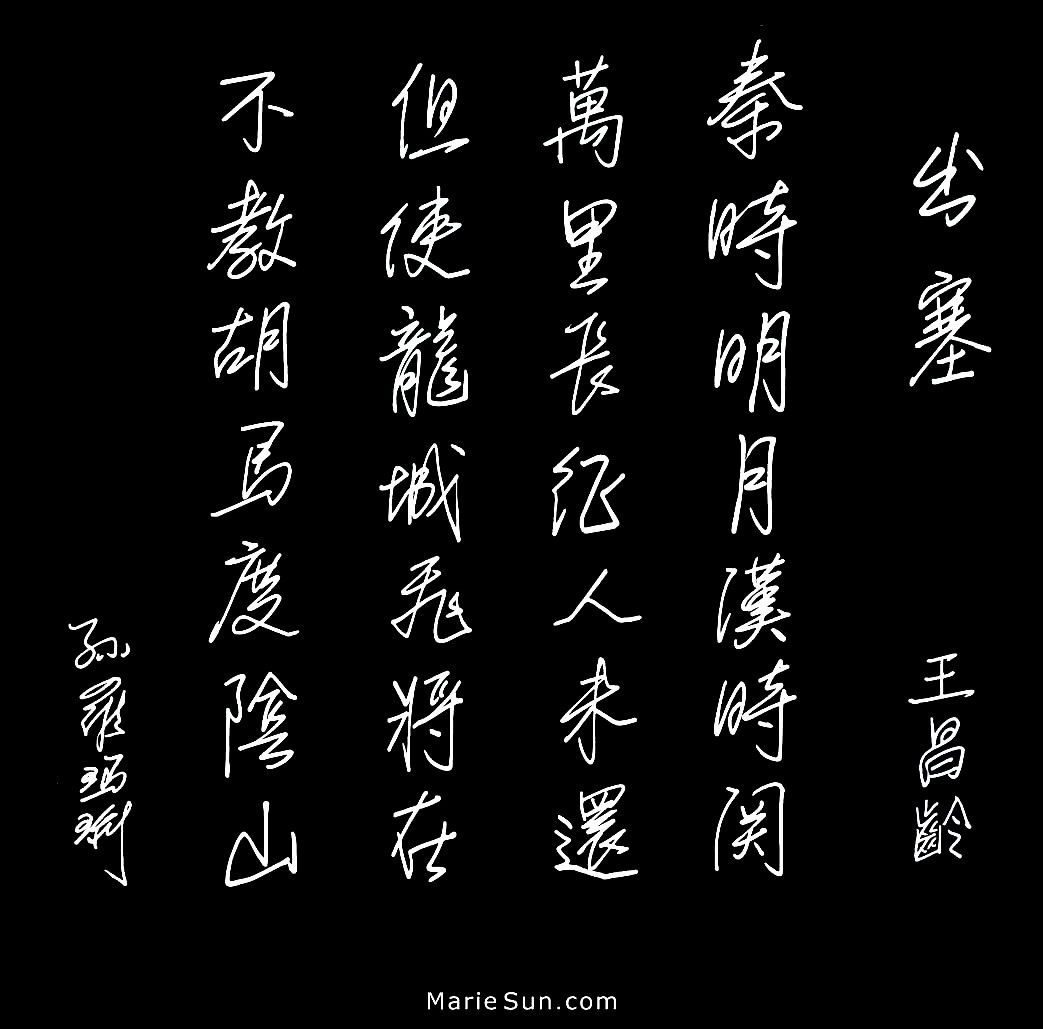

#20 Beyond the Border (Fine grape wine...)出塞

Traditional Chinese

出塞 王翰

葡萄美酒夜光杯,

欲飲琵琶馬上催。

醉臥沙場君莫笑,

古來征戰幾人回?

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

出塞 王 翰

Chū sāi wáng hàn

葡 萄 美 酒 夜 光 杯,

pú táo měi jiǔ yè guāng bēi,

欲 饮 琵 琶 马 上 催。

yù yǐn pí pá mǎ shàng cuī.

醉 卧 沙 场 君 莫 笑,

zuì wò shā chǎng jūn mò xiào,

古 来 征 战 几 人 回?

gǔ lái zhēng zhàn jǐ rén huí?

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Beyond the border Wang Han

A fine grape wine,

A luminous jade cup,

A lust to drink,

A lute calls to saddle up!

Lying drunk on the battle fields,

My lord,

Laugh not,

Since days of yore,

From battle,

How many have come back?

* * *

This is a soul-stirring

"frontier fortress" genre poem.