|

|

Go to Tang Poems (volume 1)

Tang Poems

(volume 2)

Annotated with Chinese historical references and explanations.

25 top Tang poems of the Tang Dynasty by 14 poets

|

Authors: Marie L. Sun and Alex K. Sun

(Mother and Son)

This eBook is published by

Amazon.com (美国亚马逊公司/美亚)

and sold by all Amazon stores around the world (please refer to Home page) but not by Amazon.cn yet.

Tips:

For beginners:

For beginners:

Here is the easiest way to purchase your very first kindle book - paid or free:

You don't need any Amazon Kindle Reader device to purchase any book thru Amazon.com.

You may use your PC, Laptop, Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android phone or other mobil phone etc. to purchase it and read it with Amazon Cloud Reader  (it's a free software) thru your PC, Laptop, Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android phone or other mobil phone etc.

(it's a free software) thru your PC, Laptop, Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android phone or other mobil phone etc. It also provides special instructions for people located in China or certain other foreign countries.

Calligraphy images referred by the book

may be freely copied from this website

for educational or noncommercial positive purposes (i.e., no gambling or pornography, etc.) with an attributional reference to "Marie Sun and Alex Sun or at MarieSun.com" ; other uses require explicit, written authorization by Marie Sun.

Calligraphy images referred by the book

may be freely copied from this website

for educational or noncommercial positive purposes (i.e., no gambling or pornography, etc.) with an attributional reference to "Marie Sun and Alex Sun or at MarieSun.com" ; other uses require explicit, written authorization by Marie Sun.

Preface

This book is dedicated to the memory of Marie's dear parents, Mr. Tieqing Luo (羅鐵青先生) and Ms. Wu Ma (馬勿女士), who inspired Marie's early

interest in and appreciation of Tang poetry and Chinese calligraphy.

This two part book series is structured differently from any other books on Tang poetry. Rather than simply providing a translated

poem in isolation, this series attempts to provide in-depth historical, social, and cultural background information surrounding

a poem, accompanied by multimedia links to maps, images, and/or videos scripts, including recitations in Mandarin for

each of the 25 poems. In this way, the reader can more fully understand and appreciate all the nuances of the poem in

its Chinese cultural context. This series is meant to be purchased as a set, as much of the background information is

contained in Volume 1, and this book will contain references to that volume.

A special chapter of this series is devoted to Empress Wu Zetian of the early Tang period, due to her personal

interest in composing poems, which sparked the social popularization of poetry that reached an apex during the reign

of her grandson Tang Ming Huang. Volume 1 also provides information regarding the key Battle at Tong Pass, which was

an important historical turning point for the Tang not only with respect to political and social development, but also

to the evolution of poetic styles and subject matter.

Since hand-writing or penmanship was considered part and parcel of poetic skill and talent and was also given heavy

weight in the imperial examination, Chinese charcters, writing styles, and calligraphy are also covered in Volume 2 of

this book.

In keeping with the old adage that "a picture is worth a thousand words," image/video links are provided from time to time

to accompany a poem to help put it in context.

The beauty of Tang poems is that they can evoke precise visions in an efficient conservation of words, forged into a euphonious

stream of rhyme and cadence.

When translating Tang poems into English, the poems' forms, cadences, and rhyming schemes are naturally difficult to replicate

precisely. This book attempts to retain the poems' original charm, flavor, and soul, while adhering as closely as possible

to those original forms, cadence, and rhyming schemes.

Chinese poems are often purposely designed to be ambiguous or open to interpretation. For example, in most cases, there

is no overt subject in Chinese poems, though the first person viewpoint is usually understood. Thus, the subject "I" is

often inserted as the assumed viewpoint in occidental translations. This book attempts to avoid such assumptions except

in the most obvious cases.

I hope you will find pleasure and enjoyment in perusing this book, and that you will engage in interpreting the poems

you come across in your own way and share them with your friends.

* * *

The co-author, Alex Sun, was invited by his dear grandparents, Mr. Teiqing Luo and Ms. Wu Ma, to study Chinese in Taiwan

at age 12. Alex's natural interest in learning different languages and cultures, along with his immersion for 2 years in

Chinese-speaking communities (studying another year at Beijing University in China), proved an immeasurable help in producing

this book.

An enormous thanks also goes out to Scott Shay, a computer expert and linguist who has authored

several college textbooks. With his help, we have been able to publish our first and second eBooks. Also thanks to

Benjie Sun for his editorial help and Chung-Li Sun for his spiritual support.

Copyright

All rights reserved. The scanning, uploading, and/or distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means

without the permission of the authors is illegal and strictly forbidden.

How the Information in this Book Is Organized

This book covers 25 poems, of which 22 are selected from the most popular Chinese anthology of poems, namely, "Three Hundred

Tang Poems" "唐诗三百首" compiled by Sun Zhu 孙洙 (1711 - 1778); the rest are from the "Quantangshi" "全唐诗".

In Chapter 1, the following information is provided for each poem:

(1). A brief biography of each poet, except for Li Bai and Du Fu, who are described in more detail in Volume 1, due to

their seminal influence on the East Asian poetry world (in addition, there is an entire chapter devoted to Tang Ming Huang,

the emperor patron of poetry).

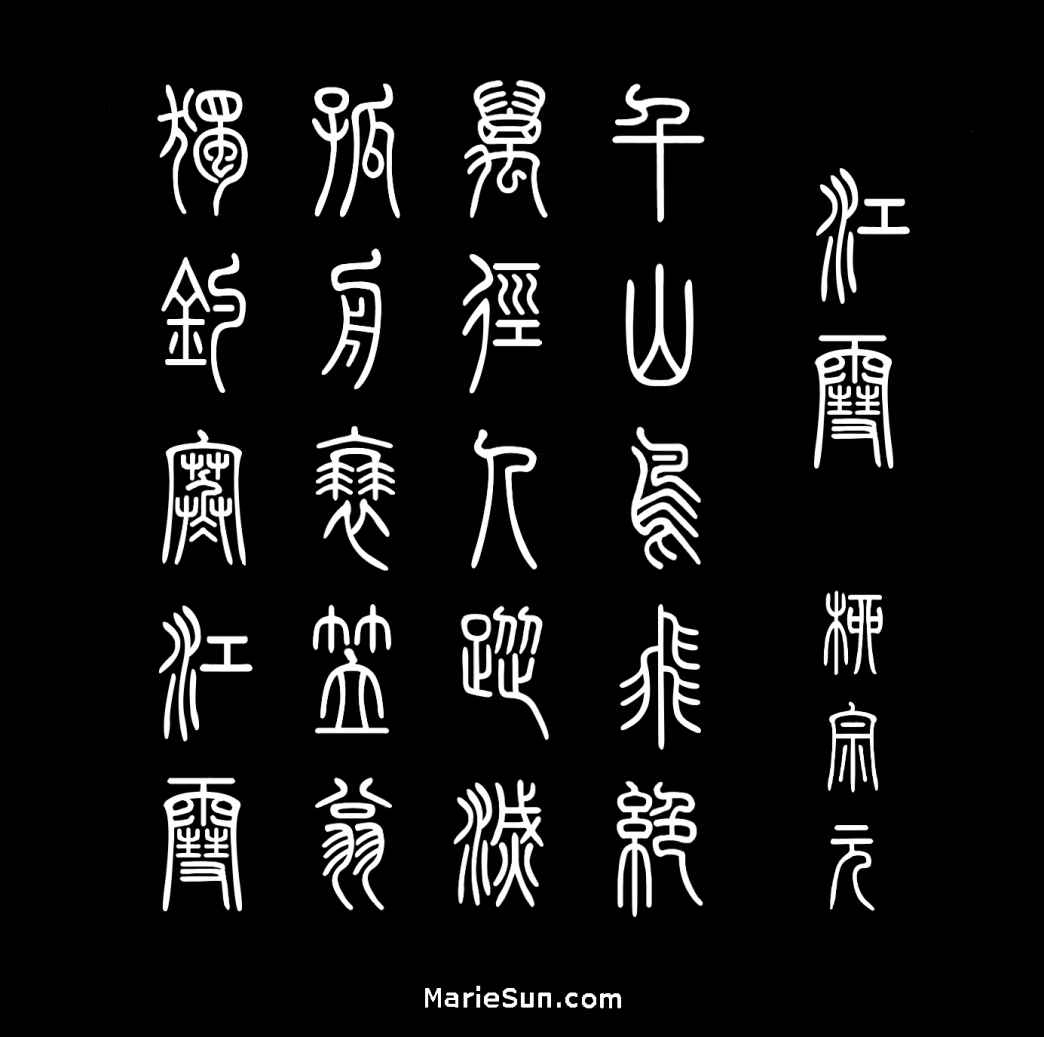

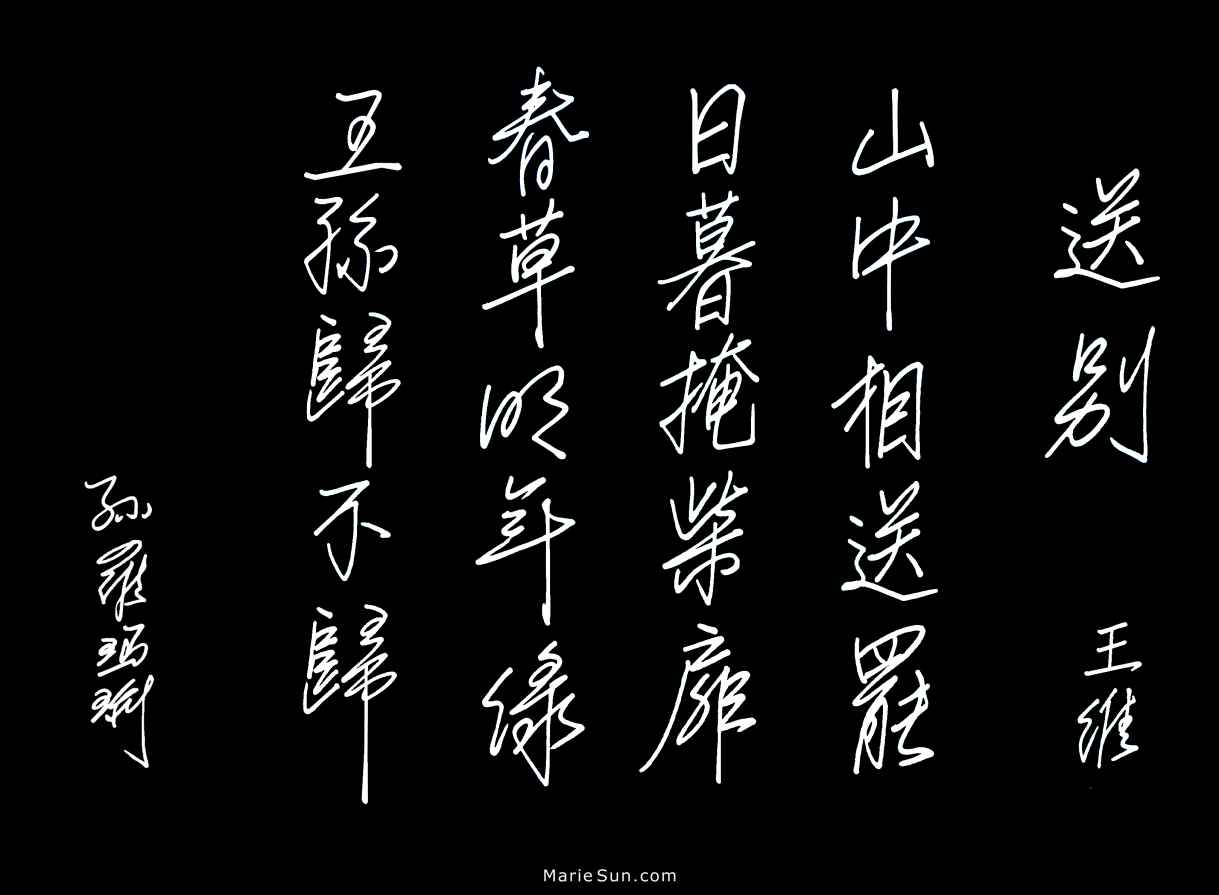

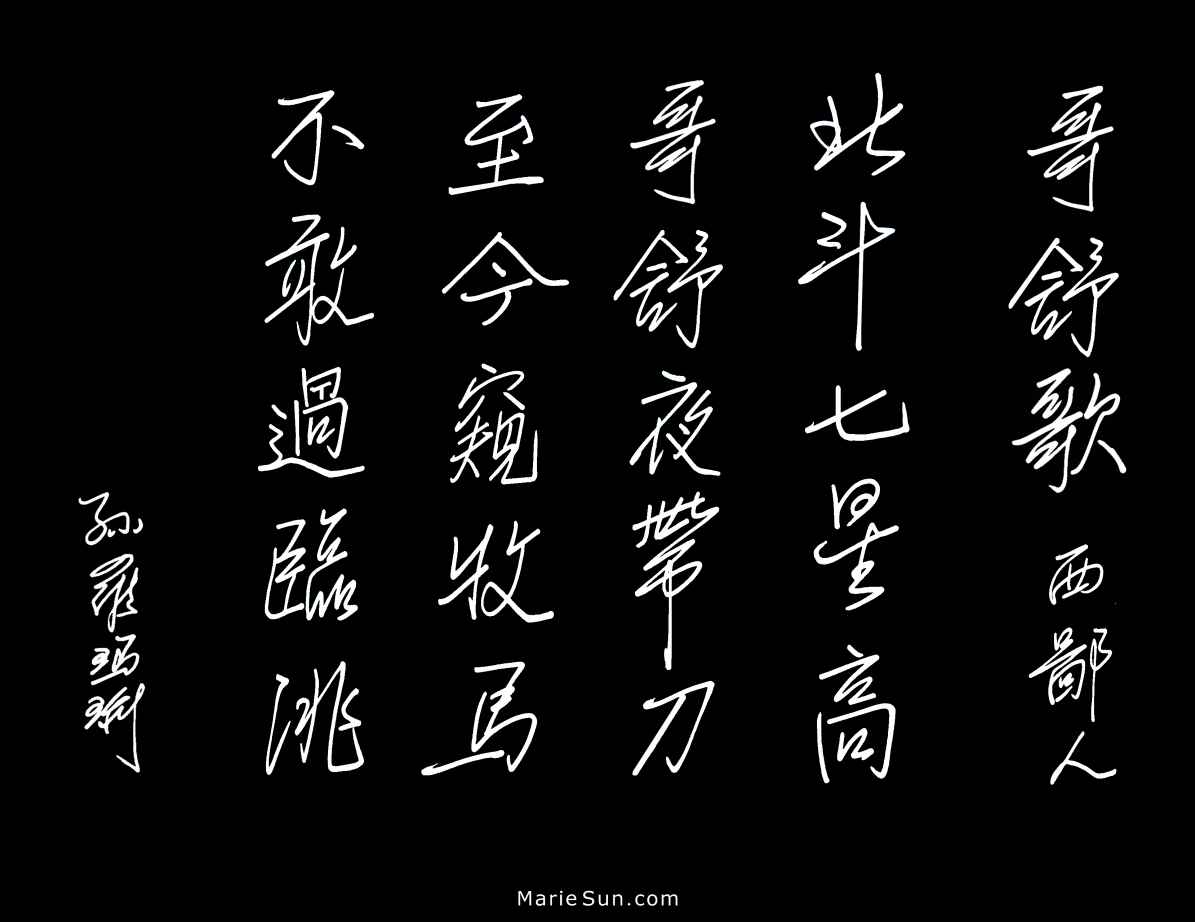

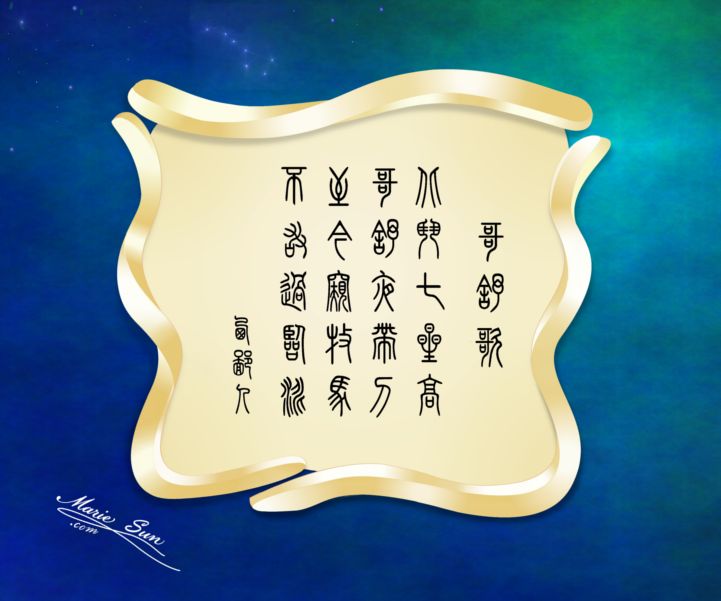

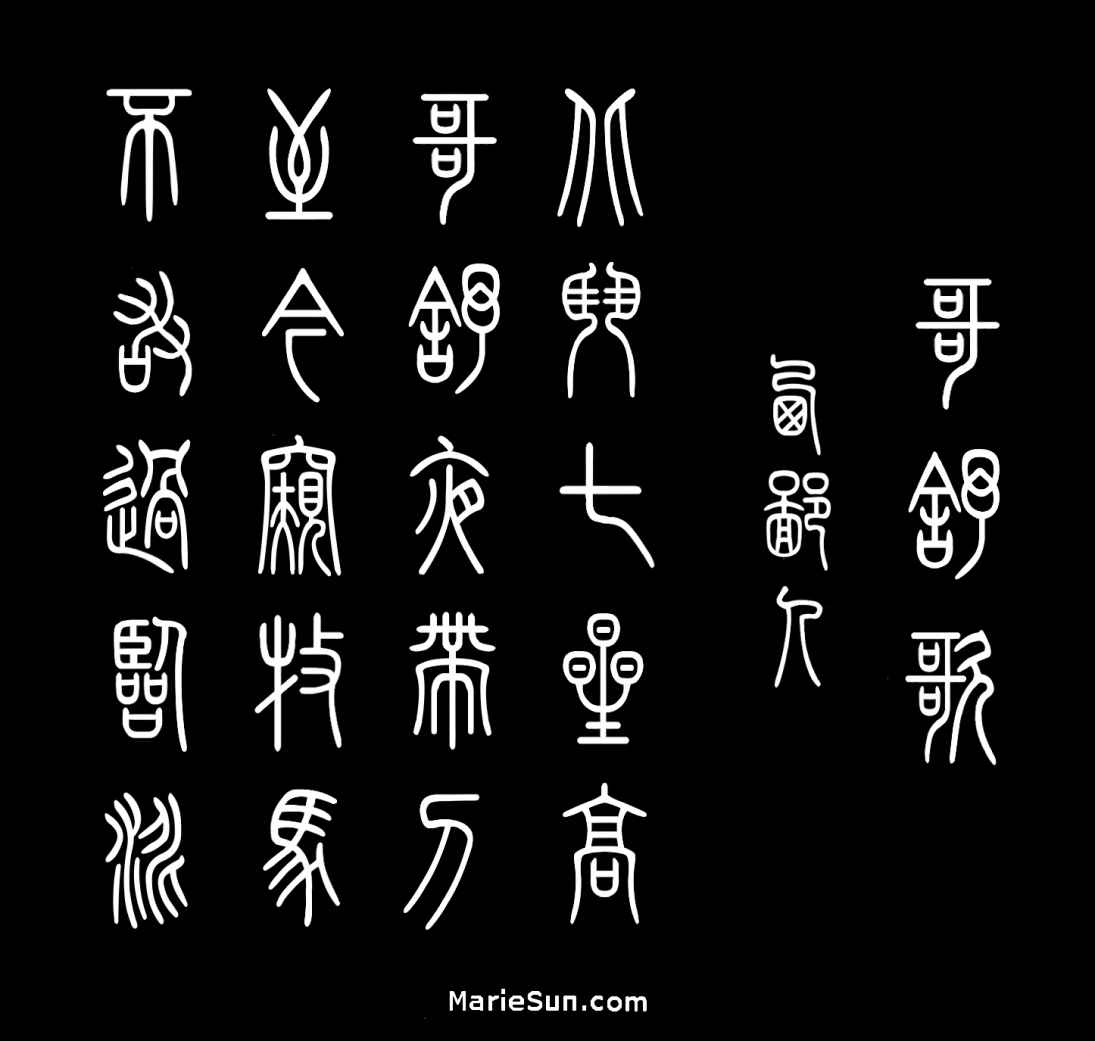

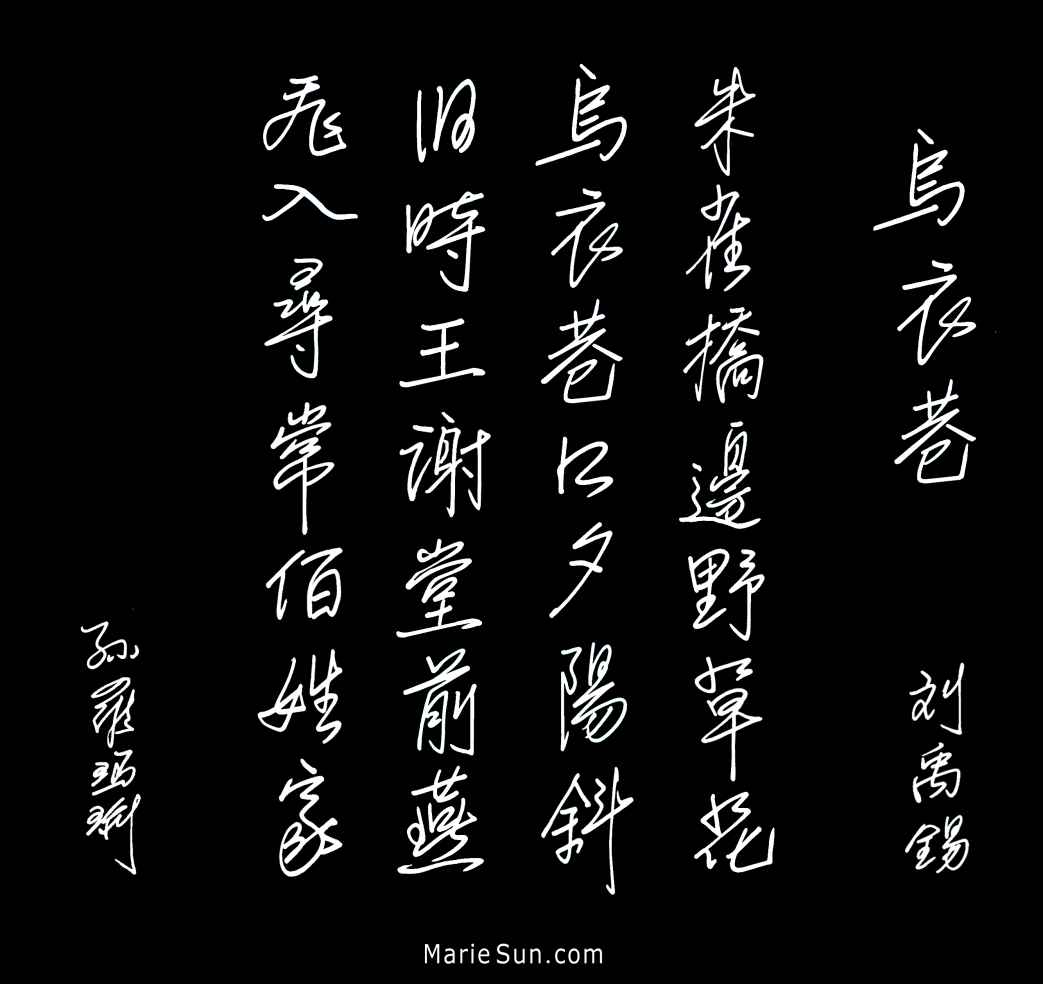

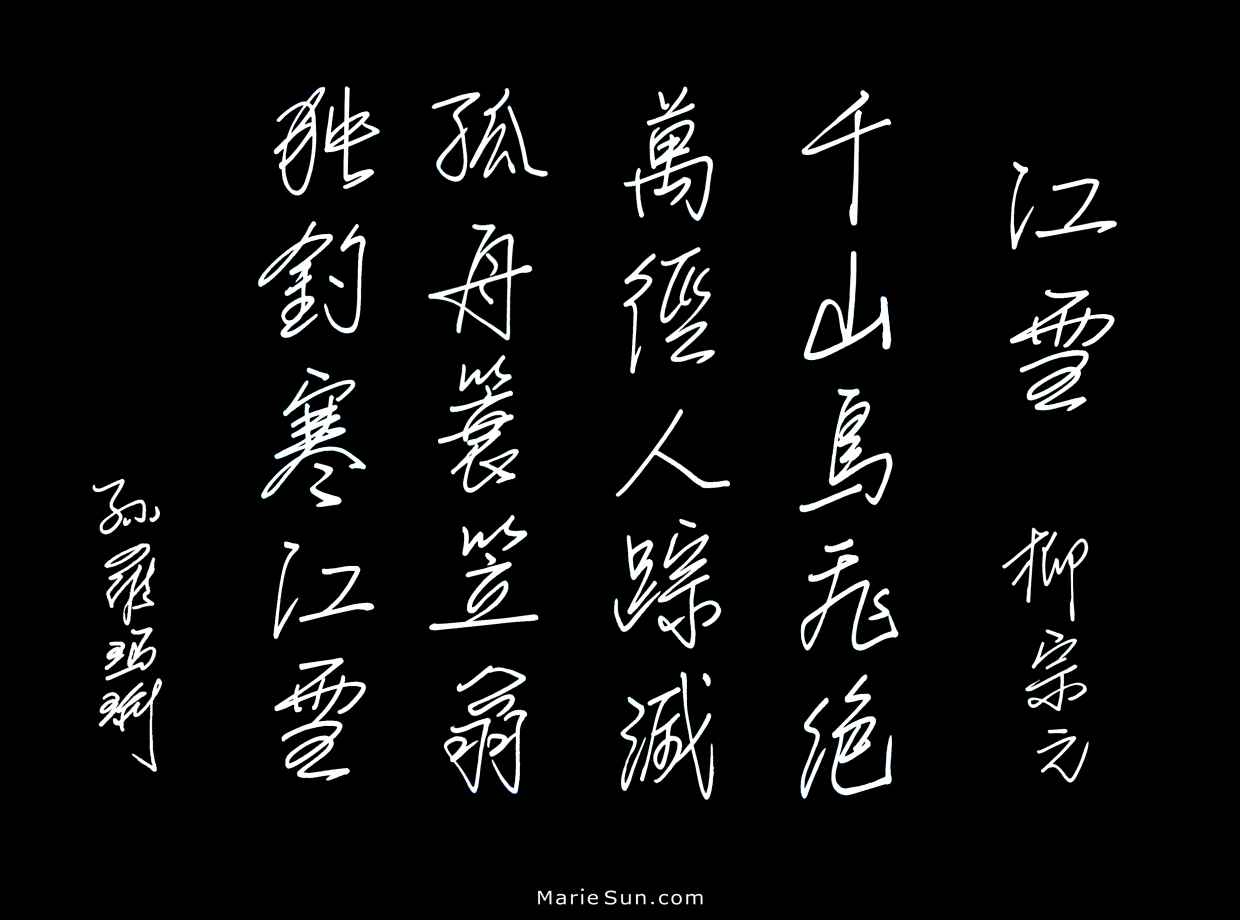

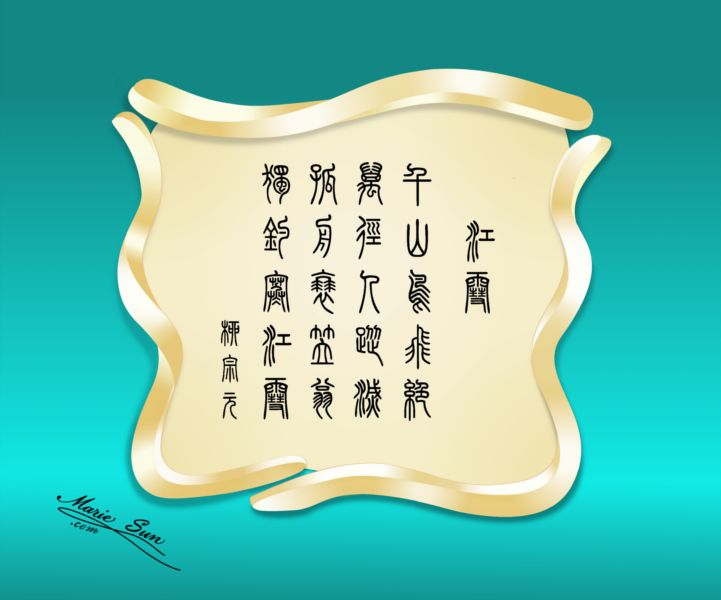

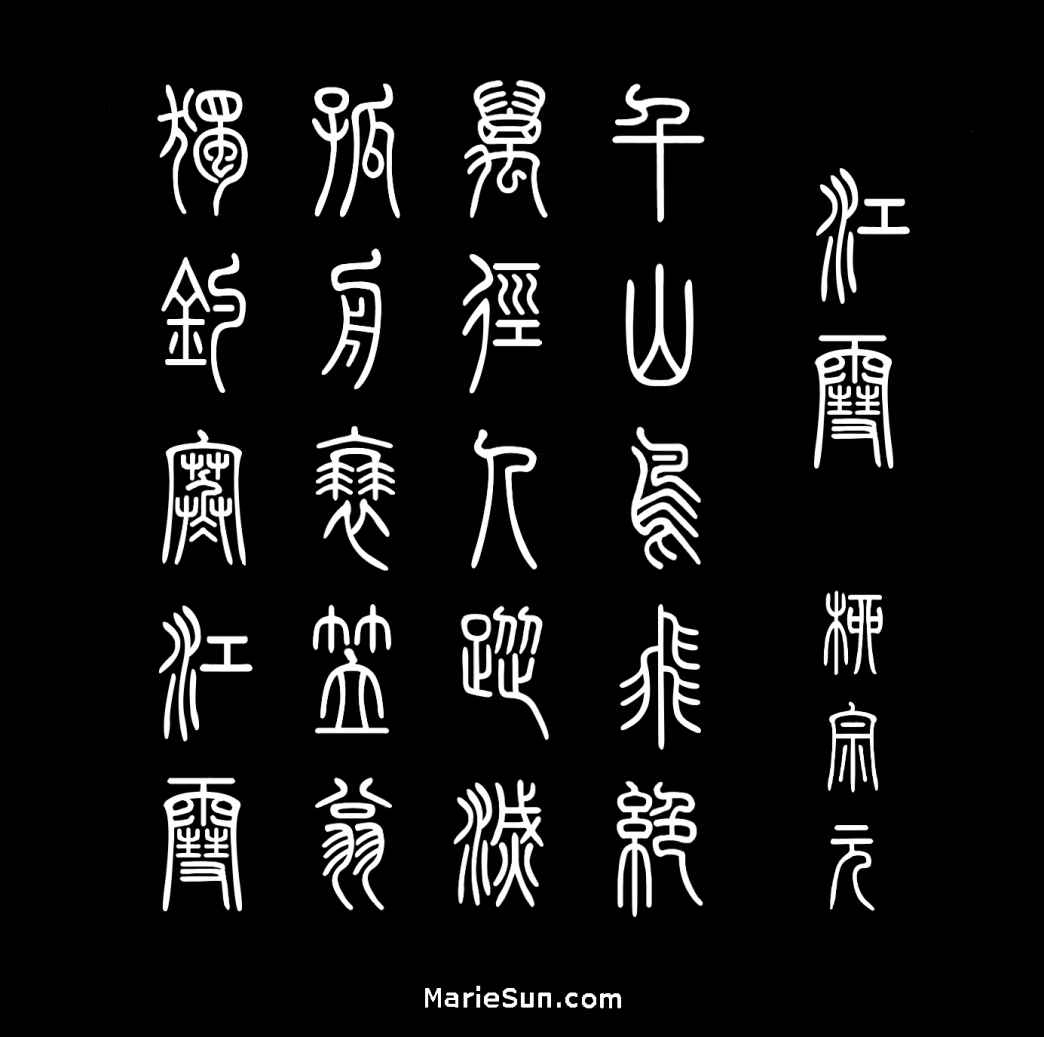

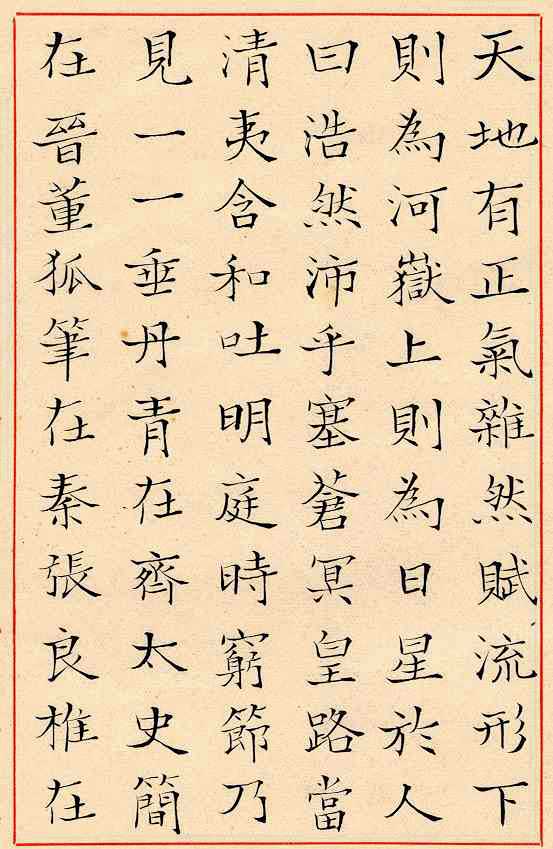

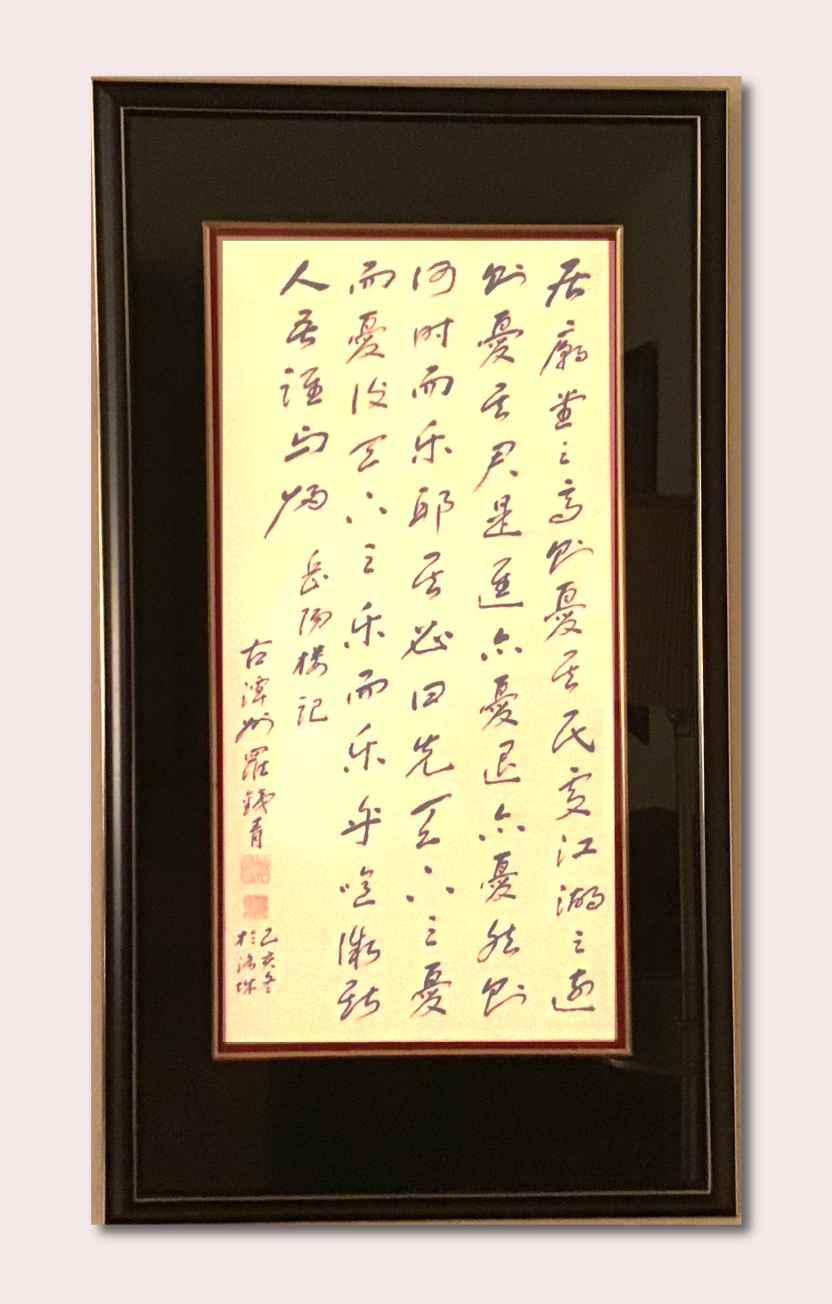

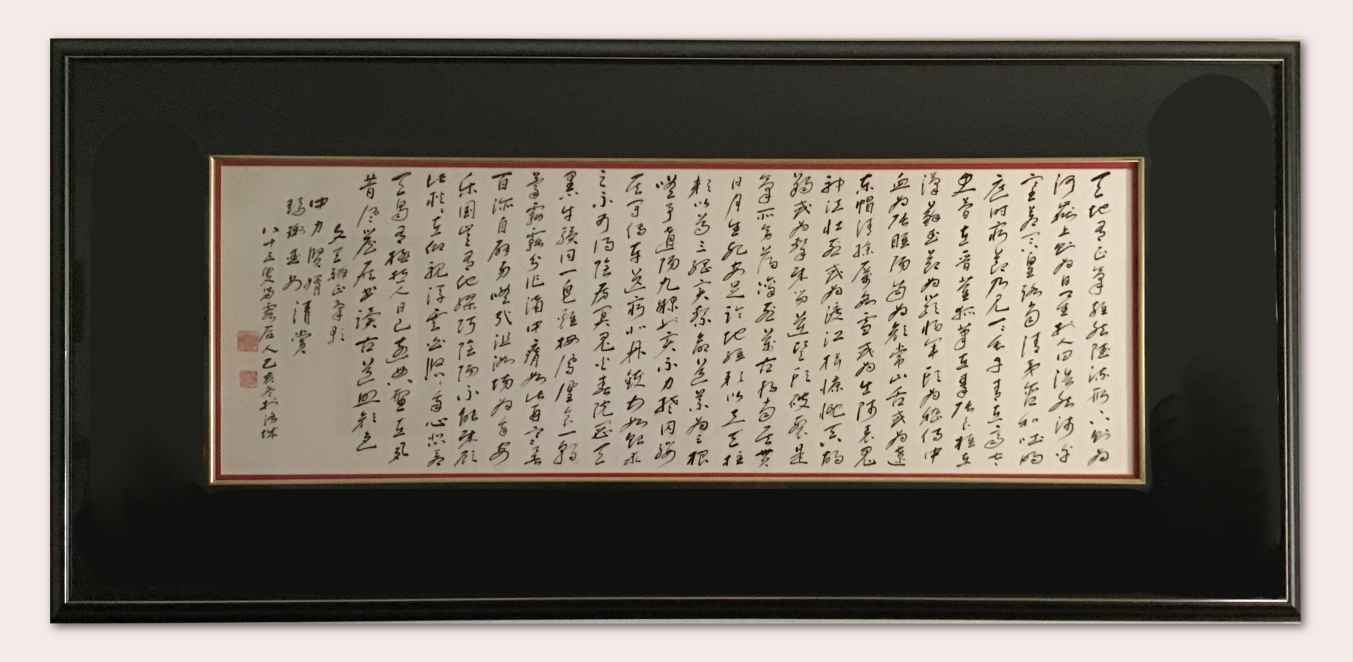

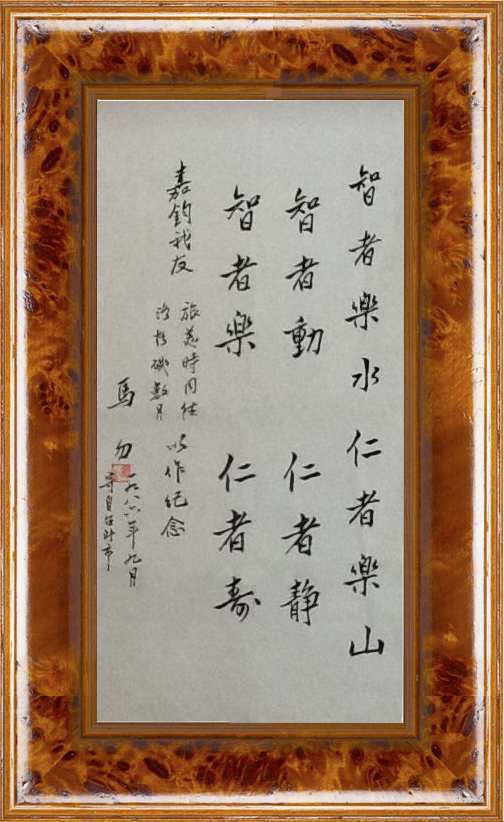

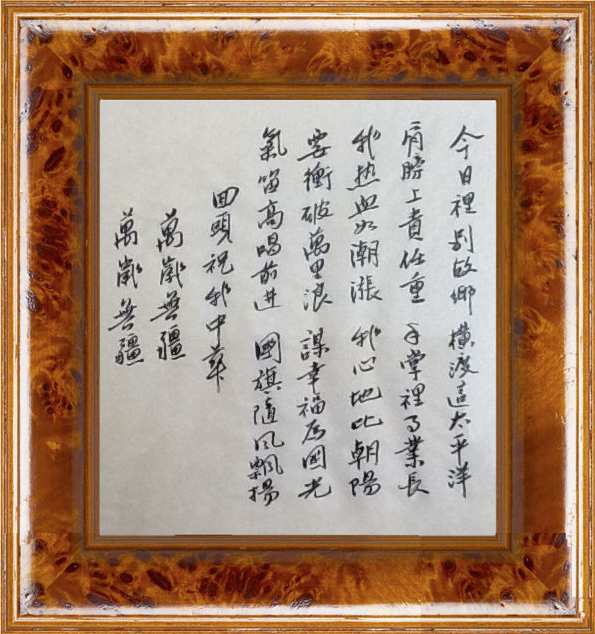

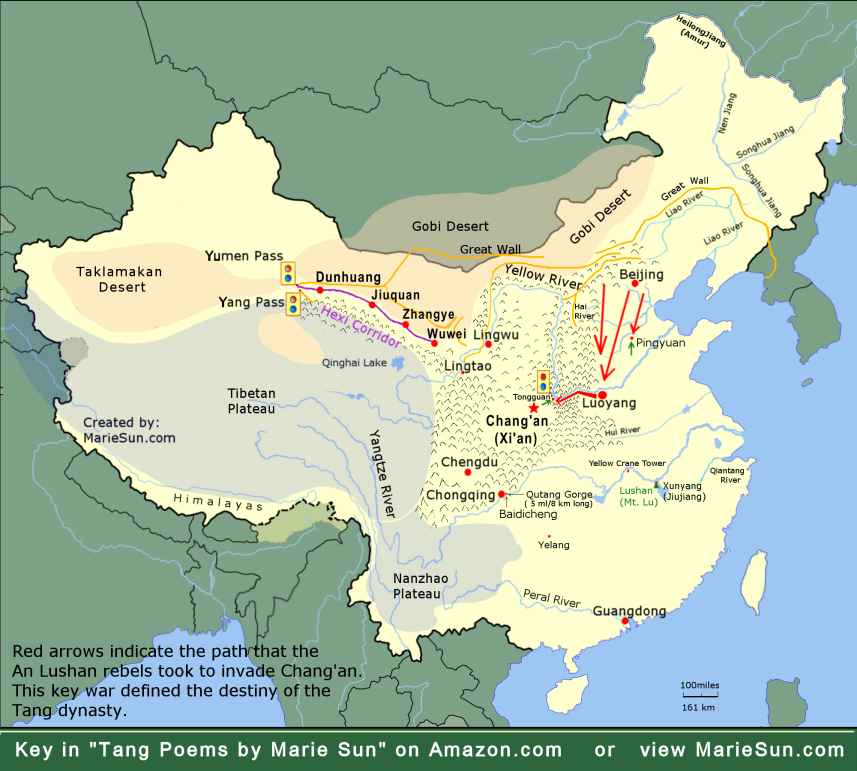

(2). Representation of each poem in the xingshu 行书 style of calligraphy; in addition, 11 poems are also presented in the

zhuanshu 篆书 style of calligraphy.

(3). An English interpretation of the poem, including comments on the historical backdrop.

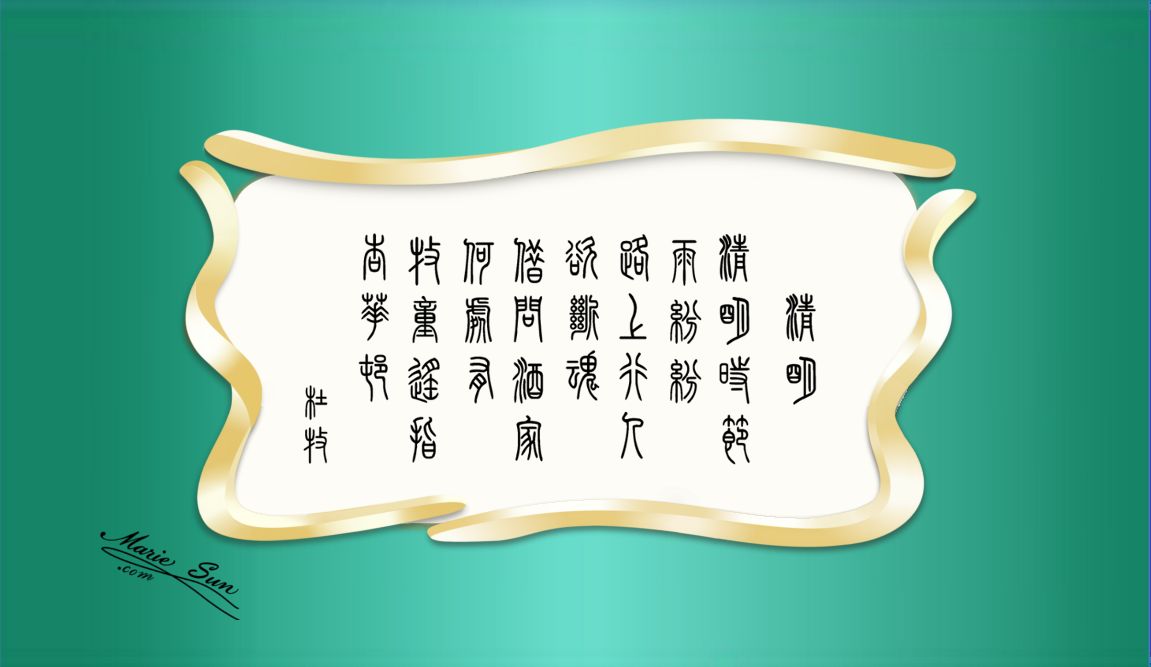

(4). Both traditional and simplified Chinese forms of the poem with pinyin annotation.

(5). A glossary of terms and names mentioned in the poem.

(6). images or videos relating to the poem or poet.

(7). A link to a recitation of the poem in Mandarin Chinese.

About the Poems

The 25 poems covered in this book are chosen out of the most popular

Chinese poetry anthology of all time, namely, "Three Hundred Tang Poems" "唐诗三百首"

compiled by Sun Zhu 孙洙 (1711 - 1778).

Most of the poems are presented after a brief biography of the poet.

The poems are numbered after eBook Tang Poems volume 1 and all poets are listed roughly in chronological order.

Chapters

1. Poets and Poems

(1). Wang Wei 王 维

Wang Wei (699 - 759; lived mostly in the High Tang period into the beginning of the Mid Tang period) was born in Yongji,

Shanxi Province 永济, 山西省, also known as

the Poet-Buddha 诗佛. Twenty-nine of his poems are included in the popular anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems". He was two years older than Li Bai and 13 years older

than Du Fu.

Born into an aristocratic family, he was the eldest of five brothers. Wang Wei was not only a talented poet and painter,

but also a famous musician, as well as calligrapher. While residing in Chang'an before taking the imperial examination

(see

Tang Poems - Volume 1), Wang's proficiency at poetry and his musical talent had helped him gain popularity at the

imperial court. Indeed, his first appointment at the imperial court was as a Deputy Master of Music. However, none of

his music compositions have survived.

He passed the imperial examination obtaining a jinshi degree title at the age of 22 with a first class award (Zhuangyuan 狀元),

thus leading forthrightly and directly to civil service career. He was soon demoted from his musical position, however,

for a petty reason. Namely, performing a Lion-dance at an "inappropriate" time. He was then assigned to the prominent and capable

Prime Minister Zhang Jiuling 张九龄 (a statesman, poet, and literary scholar, as well), as a Youshiyi remonstrate official. In the ensuing years,

he enjoyed a series of merit-based promotions. After Zhang's demotion in 737 due to the machinations of his co-Prime Minister Li Linfu

(during the Tang Dynasty, as well as others, an emperor might appoint several "prime" ministers at the same time, depending upon his inclinations), Wang Wei experienced a roller coaster like career path.

In December 755, The An Lushan Rebellion broke out. In June the next year, An Lushan occupied the capital of Chang'an

and Wang Wei was captured by the insurgent. Due to his status, he was sent under prison escort officers to Luoyang, the

capital of An Lushan's newly created state of Yan 燕 and was forced to work for the provisional government. Wang Wei

had been unable to escape Chang'an in time due to having contracted dysentery, which had made traveling difficult. After

the Tang forces recaptured Luoyang the next year from the rebels, Wang Wei was arrested and jailed again, this time by

the Tang army, who charged him with treason. His brother, Wang Jin 王缙, a high level Tang official at the time, intervened

by offering to trade away his own official rank in exchange for his brother's criminal charges being dropped. In the end, other documentary

evidence, including the poem "Ningbi Palace" 凝碧宮, which was written during his rebel captivity, proved his unwavering

loyalty to the Tang. Therefore, he was spared the criminal charges, and indeed, was assigned an official position, while

his brother, Wang Jin, was demoted only one rank level.

Eventually, Wang Wei reached the high rank of Shangshu Youcheng 尚书右丞 (a deputy prime minister in the upper schedules

of rank Four, just next to the rank of prime minister) at the end of his long career.

Landscape poet Meng Haoran (author of poem #01

Tang Poems - Volume 1) was his close friend and poetic colleague. Wang, too, wrote many landscape poems. Wang is

especially known as a poet and painter of nature. It was said of him: "The poems hold a painting within them; within

the painting there is poetry.” His poems were collected and compiled by his scholar brother, Wang Jin 王缙, under imperial

court order. A total of some four-hundred of his poems and a few of his paintings have survived, all due to Wang Jin's

efforts. Still, most of his works were lost during the An Lushan Rebellion.

He was 32 when his dear wife passed away, and he never remarried. Remaining celibate for the rest of his life and experiencing

professional upheaval, he felt unsatisfied at times with his lot. Therefore, he entrusted his spiritual

life to the study of Zen Buddhism 禅宗, seeking inner peace. He stated once, "How could I have released the lifetime of

deep sorrows that I had incurred, had there not been Zen Buddhism?" 一生几许伤心事,不向空门何处销. In his will he donated many of his

buildings and properties to the local, public zen organization.

Due to his affinity towards nature and his faithful adherence to Zen Buddhism, his poems (as well as his paintings)

are filled with a feeling of tranquility, peacefulness, and aloofness from worldly affairs.

In China (and other parts of East Asia), Du Fu, Li Bai, and Wang Wei came to be regarded as representing Ruism/Confucianism

儒家, Taoism/Daoism 道家, and Zen Buddhism/Chan Buddhism 禅宗佛家 respectively.

(a brief summary of these three fields).

Wang Wei's paintings:

1.

"Snow Stopped over a Creek 江干雪霁" thru Baidu.

2.

"Snow Over a Creek" "雪溪图" thru Baidu.

3.

"Snow Over Rivers and Mountains (wikipedia)" - Wang Shimin's painting in the style of Wang Wei.

Zen temples, gardens, and other scenes:

1.

Zen Buddhist temples thru Baidu.

2.

Zen concept gardens thru Baidu.

3.

A Zen spirit can be sensed in some of these images - thru Baidu.

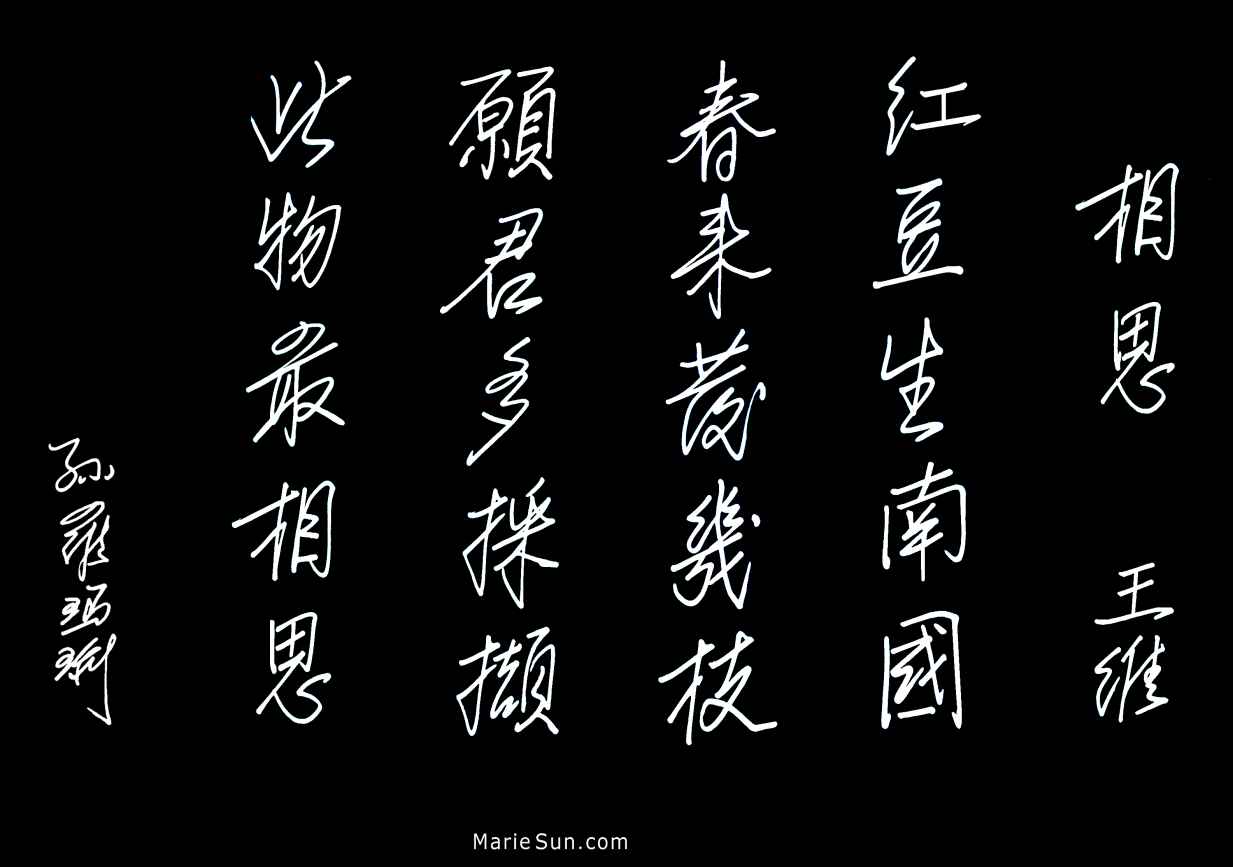

Throughout this book, the poems presented in the taben style (white characters on black background) are listed in the traditional

Chinese manner - written in vertical columns from top to bottom and from right to left without punctuation. However,

the rest of the contents are presented in the "modern" western approach, with characters in horizontal rows from left

to right.

poem #26 (Poems #1 to #25 are contained in Volume 1)

Traditional Chinese

相思 王維

紅豆生南國,

春來發幾枝。

願君多採擷,

此物最相思。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

相 思 王 维

xiāng sī wáng wéi

红 豆 生 南 国,

hóng dòu shēng nán guó ,

春 来 发 几 枝。

chūn lái fā jǐ zhī .

愿 君 多 采 撷,

yuàn jūn duō cǎi xié ,

此 物 最 相 思。

cǐ wù zuì xiāng sī.

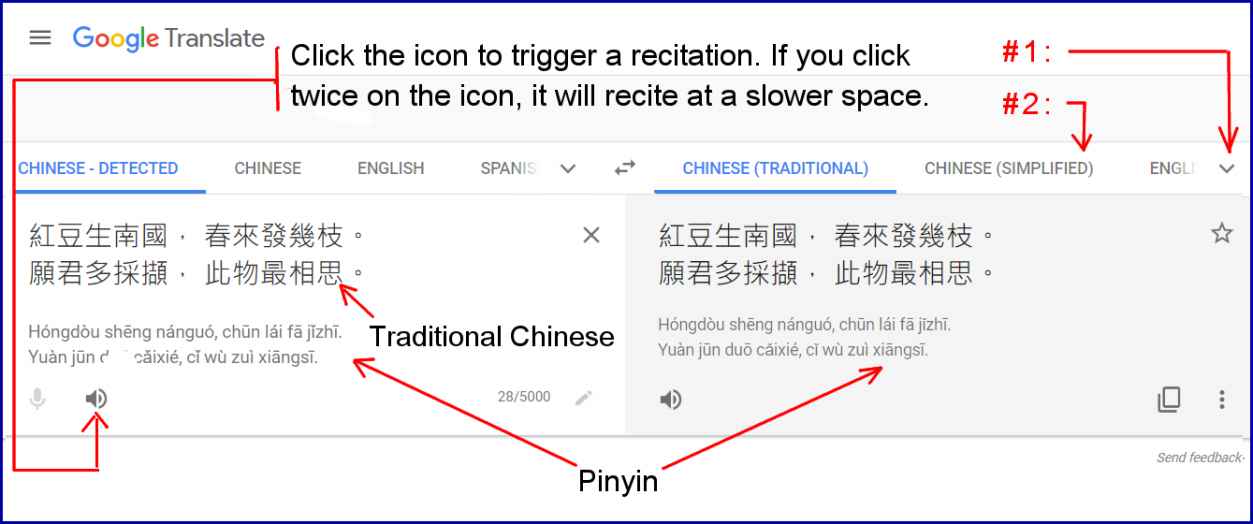

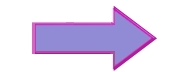

* Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Notes *:

Recitation 1: Click it to listen to a recitation of the poem in Mandar Chinese

and to view a transliteration into pinyin.

Recitation 2: Click it to listen to recitation through other options.

Deep Yearning Wang Wei

The red beans grow in the southern lands;

Each spring their branches spread anew.

Please gather as much as you wish, my lord,

These incarnations of yearning love most true.

* * *

The red bean, also known as the love-bean, is the seed of the Adenanthera pavonina and is shaped like a red human heart.

The attractive Abrus precatorius seeds are also called the love-bean by the Chinese, though they are shaped differently.

From this poem, one can perceive that Wang Wei was a very passionate and romantic person. Unfortunately, at age 32,

his wife passed away and he never remarried. It seems that Wang Wei was not just affectionate, but also only had one

heart to give!

* * *

红: red, vermilion, blush, flush 豆: beans, peas, bean-shaped 红豆: "longing bean" (相思豆), "Red Lucky Seed" or

Adenanthera pavonina 生: birth, life, living, lifetime 南: southern part, south, southward 国: nation, country,

nation-state

春: spring 来: come, coming, return, returning 发: grow, send out, issue, dispatch, hair 几: a few, small table 枝: branches,

limbs, branch off

愿: wish, desire, want, ambition, sincere, honest, virtuous 君: you (a respective way to address to a male), prince, sovereign,

monarch, ruler, chief 多: many, much, more than, over 采: gather, collect, pick, pluck 撷: pick up, gather up, hold in lap

此: this, these, in this case, then 物: thing, substance, creature 最: most, extremely, exceedingly 相思: to miss each other,

to be in love with each other, longing for someone, love and endearment

View the following images:

1. Chinese calligraphy 红豆生南国书法:

view thru Google or

Yahoo.

2. Museum exhibits of Wang Wei paintings and calligraphy (search results may be broader than the subject matter):

搜寻王维字画于故宫博物馆:

view thru Google or

Baidu.

3. love-beans 相思豆:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

...

...

...

...

...

#29 Send Off 送別

Traditional Chinese

送 别 王維

山中相送罷,日暮掩柴扉。

春草明年綠,王孫歸不歸?

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

送 别 王 维

Sòng bié wáng wéi

山 中 相 送 罢,日 暮 掩 柴 扉。

Shān zhōng xiāng sòng ba, rì mù yǎn chái fēi

春 草 明 年 绿,王 孙 归 不 归?

Chūn cǎo míng nián lǜ, wáng sūn guī bù guī

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Send Off Wang Wei

We bid each other adieu in the mountains,

As dusk descends, I close my wicker door.

The green grass will return again next spring;

Will your young lordship return ever more?

* * *

The poem describes a farewell on a mountain side, as an older gentleman sees off a young man striking out into the world.

With a few pen strokes, the poet paints a melancholic scene of a hazy mountain at twilight. After returning to his wicker

gate and closing it, the elder is left to wonder how long it may be until the young man returns again to visit. A meeting

again next spring is what he deeply hopes for, but no one knows the future - the world is full of unpredictability,

and anything could happen. A lingering touch of sadness and suspense invoked by just a few simple words! While the relationship

between the two men in the poem is left unknown, yet it remains a masterful sketch of human emotion through indirect, yet concise, imagery.

* * *

送别: see off, farewell

山: mountain, hill 中: in the midst of, center, middle, central, hit (target), attain 相: each other, mutual, reciprocal

送: see off, send off, dispatch, give 罷: finish, cease, stop, give up

日: sun, day, daytime 暮: sunset, dusk, evening, ending 掩: shut, conceal, to cover (with the hand), ambush 柴: firewood

扉: door panel 柴扉: wicker gate

春: spring 草: grass 明: bright, light, brilliant, clear 年: year, new-years, person's age 明年: next year 綠: green

王: royal, king, ruler, surname 孙: descendant, grandchild, surname 王孙: The descendant of a royal or notable family, respectful

form of address for a friend 归: return, return to (home), return to, revert to 不: no, not, un-, negative prefix

View the following images related to the poem:

Chinese calligraphy 王维 送别诗 书法:

view thru Google or

Baidu.

...

...

...

...

... omitted

...

...

...

(2). Xi Biren 西鄙人

The name "Xi Biren" 西鄙人 is an alias meaning "a humble person from the western border." Xi's real name is unknown, as

are his birth year and birth place. In fact, there are no known records of his past or background. Only one of his poems,

"Geshu Ge/Geshu Song" 哥舒歌 - describing the famous Tang General Geshu Han's 哥舒翰 early life on the western frontier -

is in the the popular anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems."

poem #31

Traditional Chinese

哥舒歌 西鄙人

北斗七星高, 哥舒夜帶刀。

至今窺牧馬, 不敢過臨洮。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

哥 舒 歌 西 鄙 人

Gē shū gē xi bì rén

北 斗 七 星 高, 哥 舒 夜 带 刀。

Běi dǒu qī xīng gāo, gē shū yè dài dāo

至 今 窥 牧 马, 不 敢 过 临 洮。

Zhì jīn kuī mù mǎ, bù gǎn guò lín táo

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Geshu Song Xi Biren

The Big Dipper dangling on high,

With sabre, Geshu patrols the night.

Till now, they've preyed upon pasture horses,

But, dare not cross Lingtao,

In awe of Geshu's might.

* * *

General Geshu 哥舒

His formal name was Geshu Han 哥舒翰, and he came from a Turgesh tribe in Central Asia. Born into a well-to-do family,

he could speak, read, and write Chinese. Though he led a life of debauchery during his youth, he became a capable general

who defeated multiple Tufan 吐蕃 attacks in the Tibetan Plateau 西藏高原 around Qinghai Lake 青海湖. Hence, he made a respected

and feared name for himself among the Tufan tribes.

Poet Xi Biren wrote this poem praising the brave and invincible General Geshu and his outstanding achievements in the

far western frontier region around Lingtao. Geshu,however, met a tragic ending.

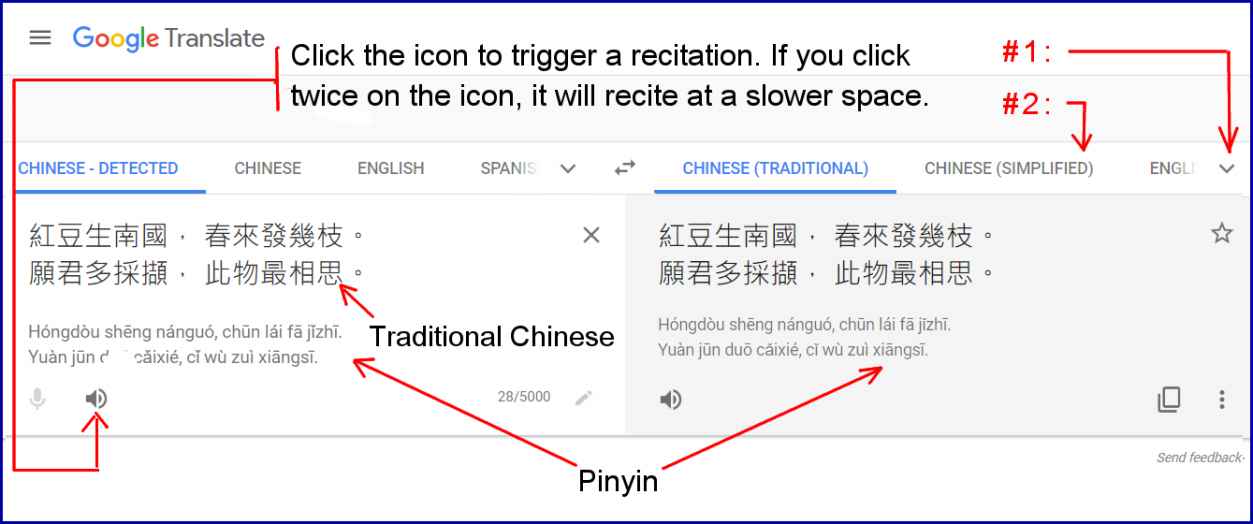

In December of 755, the An Lushan Rebellion broke out and the rebels quickly captured Luoyang 洛阳. In March 756, the

rebels were ready to break through the key garrote fortress at Tong Pass/Tongguan 潼关 and invade Chang'an.

Tong Pass was located about 120 mi/193 km to the west of Luoyang and 80 mi/129 km to the east of Chang'an. To its north

was the turbulent Yellow River, and to its south, the soaring Qinling 秦岭 (or Qin Mountains). The road to the Tong Pass

from the east was very narrow, bounded for some 40 miles/65 kilometers by rough terrain, with some sections, especially

near the Pass, allowing only one war chariot to pass through at a time. And it was the only route for military chariots and people to get in or out of Chang'an's east side.

Due to its geographical position, the Pass was

the most important military strategic point protecting access to Chang'an and its surrounding areas.

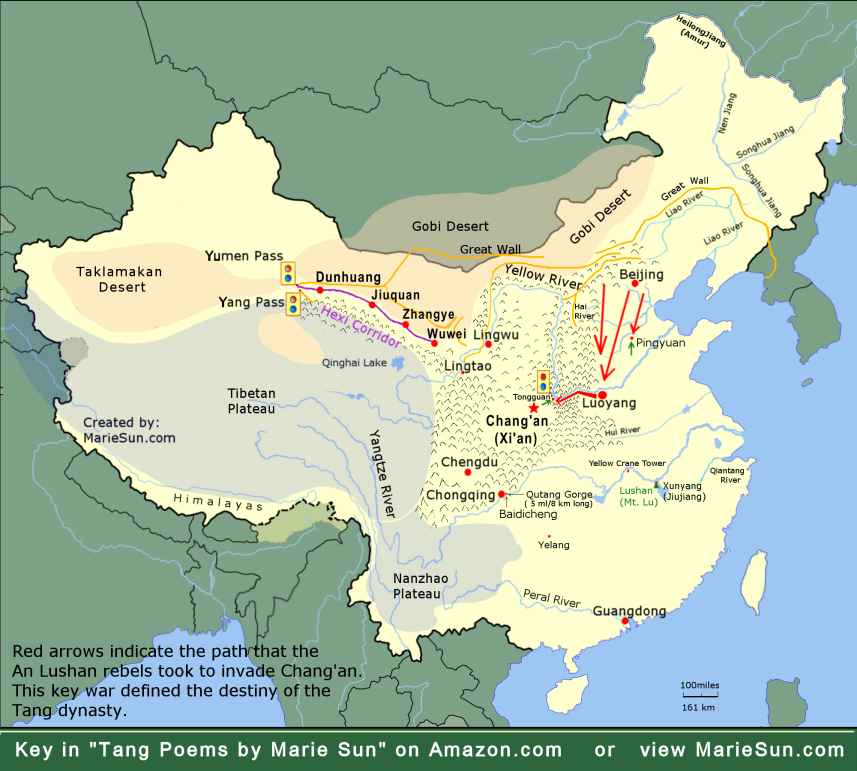

The red arrows show the main pathways that the An Lushan rebels took from December 755 to June 756 to invade Chang'an:

|

(This map is based on current Chinese territory. Not all mountains, rivers, or plateaus are displayed. The map's outline

was retrieved from

Joowwww [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

(You may copy this map from mariesun.com for non-profit, educational purposes of uses for free.

您可以从 mariesun.com 复制此地图用于非营利性教育用途。)

View Tong Pass/Tongguan relics:

thru Google,

Baidu,

Bing or

Yahoo.

During this critical time, Geshu was called in by the imperial court to take over the positions of generals Feng Changqing

and Gao Xianzhi 封常清 與 高仙芝 in the defense of the Tong Pass against the An Lushan's rebel forces. The two capable generals

had been beheaded for not following the military strategies issued by the court.

Geshu and An Lushan, an imperial general himself, had never gotten along, as Geshu had always looked down on An Lushan

for his "lack of culture". The emperor, Tang Ming Huang, tried once to alleviate the friction by holding a banquet in Chang'an

for the two of them, but to no avail.

Upon investigating the terrain surrounding the Tong Pass, General Geshu knew the only and the best way to defend Chang'an

was through a defensive strategy, i.e., the same strategy advocated by the two previous generals. The court, however,

continued to think otherwise.

In June of 756, as imperial edicts kept piling up, urging him to take immediate action and attack the rebel forces,

Geshu knew his fate - either to attack and fight an unwinnable battle or be executed by the court in the same manner

as his predecessors. Without any other options, he was forced by court machinations and intrigue to follow the flawed

military strategies advocated by the corrupt and incompetent Prime Minister Yang Guozhong 楊国忠, cousin to Yang Guifei

揚貴妃 - Emperor Tang Ming Huang's favorite consort.

Geshu eventually followed orders and suffered an overwhelming defeat. In this key battle, only 8,000 imperial soldiers

survived and returned to base out of an original army of some 200,000 soldiers. More than 90 percent of Geshu's forces

were decimated. His subordinates, seeing the hopelessness of the situation, got Geshu intoxicated, bound him to a horse,

and

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The An Lushan Rebellion was, indeed, a watershed moment for the Tang Dynasty - as well as for General Geshu. (For more

background information on An Lushan, please refer to Tang Poems Volume 1)

* * *

歌: song, lyrics, sing, chant; praise

北斗七星: the Big Dipper 高: high, tall, lofty, elevated

夜: night, dark, in night, by night 带: carry, belt, girdle, band, strap, zone 刀: sabre, knife

至今: till now, till today 窥: pry on, peep, watch 牧马: pasture horse

不敢: dare not 过: go across, pass, pass through

临洮: A county located in present-day Gansu Province 甘肃省, not too far from Lanzhou city 兰州市, along the the eastern bank

of the Tao River 洮河 (a tributary of the Yellow River 黄河). The area was established as Lingtao County in 753 by Geshu.

It is located to the east of Lake Qinghai 青海湖.

View the following images:

1. Chinese calligraphy 北斗七星高书法:

view thru Google or

Baidu.

2. The Big Dipper 北斗星:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

3. Lingzhao 临洮:

view thru Google

or

Baidu.

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

#35 Grass 草 (赋得古原草送别)

Traditional Chinese

草 白 居 易

離離原上草, 一歲一枯榮。

野火燒不盡, 春風吹又生。

遠芳侵古道, 晴翠接荒城。

又送王孫去, 萋萋滿別情。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

草 白 居 易

cǎo

bái jū yì

离 离 原 上 草, 一 岁 一 枯 荣。

lí lí yuán shàng cǎo, yī suì yī kū róng.

野 火 烧 不 尽, 春 风 吹 又 生。

Yě huǒ shāo bù jìn, chūn fēng chuī yòu shēng.

远 芳 侵 古 道, 晴 翠 接 荒 城。

Yuǎn fāng qīn gǔ dào, qíng cuì jiē huāng chéng.

又 送 王 孙 去,萋 萋 满 别 情。

Yòu sòng wáng sūn qù, qī qī mǎn bié qíng.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Grass Bai Juyi

Grasses spread over the vast prairie,

withering and returning each year.

Wildfires cannot wipe them out;

A gentle Spring breeze

And again they sprout.

Their far away fragrant verdure

Invades the ancient routes;

Under cloudless skies

Their green entwines ruins.

My dear friend,

I'm seeing you off again,

And even the lush foliages

Feel the parting pain.

* * *

The poem paints a picture of a beautiful, thriving prairie dotted with sentimental relics, capturing the vibrant and

nostalgic beauty that can arise from the sometimes deep melancholy that commonly accompanies the partings of loved

ones.

It was composed by Bai Juyi at a very early age - around 16 - and became very popular.

The first four verses - "Wildfires cannot wipe them out - a gentle Spring breeze - and again they sprout" has long

become a Chinese classic quote. It signifies that no matter how dire the situation, life will roar back and thrive

again. It is a sentiment full of vitality and also representative of Bai Juyi's life attitude.

* * *

离离: abundance, plenty 原: plain, former, original, primary, raw 上: up, top, superior, highest 草: grass, straw, thatch,

herbs ,一岁: each year , one year 枯 : dried out, withered, decayed 荣: prosper, glory, honor, flourish

野火: wildfire 烧: burn, bake, heat, roast 不尽: not deplete, not exhaust, not use up 春风: spring breeze, spring wind 吹:

blow, puff, brag, boast 又: again, in addition, also, and 生: life, living, birth, lifetime

远: distant, remote, far, profound 芳: fragrant, virtuous, beautiful 侵: invade,

encroach upon, raid 古: ancient, old, classic 道: path, road, street, method, way 晴: clear weather, fine weather 翠: bluish

green, color green, green jade 接: connect, catch, receive, continue 荒: wasteland, desert, uncultivated 城: the walls

of a city, to surround a city with wall, town, city, castle, municipality

又: again, and, also, in addition 送: see off, send off, dispatch, give 王孙: archaic form of respectful address of a

friend, someone who is born into a noble family 去: depart, leave, go away 萋: luxuriant foliage, crowded 满: fill, full,

satisfied 别: separate, other, do not 情: feeling, sentiment, emotion

View the following images related to this poem:

1. Prairie scenery in China 中国草原风光:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

2. Chinese calligraphy 离离原上草书法:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

Liu Yuxi 刘禹锡

Liu Yuxi (772 - 842; lived in Mid and Late Tang periods) was born in Suzhou, Jiangsu Province 苏州, 江苏省. His family

was originally from Luoyang 洛阳. In order to escape the An Lushan Rebellion, the whole family moved to Suzhou. Around

800 of his poems are extant, of which four are included in the popular anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems."

In 793, at age 21, he passed the imperial examination (see

Tang Poems - Volume 1) obtaining jinshi title degree. Soon thereafter, he also passed the advanced imperial

examination and started his civil service career right away in the capital of Chang'an. In 806, at age 34, he was "suppressed"

in a political struggle due to his association with the Yong Zhen Ge Xin 永贞革新 reform movement. The leader of the movement,

Wang Shuwen 王叔文, was executed; Liu was banished along with Liu Zongyuan (author of poem #37 "River Snow" and also Yuxi's

good friend) and six other movement supporters to various remote areas of the empire. Then, 9 years later, in 815,

he was recalled to Chang'an to resume his post. That same year he was banished again due to his penning of political

satire poems. Then, once again, 13 years later, he was called back at age 56 to Chang'an by a new emperor. He spent

a total of 22 years in exile.

Liu was strong-willed, broad-minded, and passionate. He upheld the truth and refused to simply follow the crowd. No

matter whatever frustrating environment he encountered, he was never defeatist, but always faced the situation with

a positive and unyielding fighting spirit.

His banishment forced him to travel to various remote areas, such as present-day Changde city in Hu'nan Province 湖南省; Zunyi

city in Guizhou Province 贵州省; Qingyuan city in Guangdong Province 广东省; and Fengjie County and Chongqing city, both in Sichuan

Province 四川省. This provided him the opportunity to come in contact with different ethnic groups and cultures.

He took advantage of his experience, infusing and enriching his poetry and essays with flourishes informed by local

folk songs and customs.

Liu was an associate of Bai Juyi 白居易 and had a major influence on folk-style poems - yuefu 乐府. He was not only an exceptional

folk-style poet, but also a well-known philosopher and essayist. One of his most famous prose works is "A Motto of

(my) Humble Abode" "陋室铭".

"The Black Clothes Alley" is one of the four of his poems included in the popular anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems."

It was said that after his good friend Bai Juyi read this poem, he pondered it for a moment and then repeatedly recited

it rhythmically for a while. The suggestion was that Bai really enjoyed the poem and appreciated his old friend's competence

and talent.

Liu spent most of his later years in close contact with his lifelong friend, Bai Juyi, both of whom lived in

Luoyang, not far from each other. Being the same age and sharing the same interests, they were able to reminisce together

and support each other spiritually, which is a blessing for the elderly. Liu died at age 70. Four years later, his

good friend Bai Juyi followed him into the next world.

#36 Black Clothes Alley 乌衣巷

Traditional Chinese

烏衣巷 劉禹錫

朱雀橋邊野草花, 烏衣巷口夕陽斜。

舊時王謝堂前燕, 飛入尋常百姓家。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

乌 衣 巷 刘 禹 錫

Wū yī xiàng liú yǔ xī

朱 雀 桥 边 野 草 花,

Zhū què qiáo biān yě cǎo huā,

乌 衣 巷 口 夕 阳 斜。

wū yī xiàng kǒu xī yáng xié.

旧 时 王 谢 堂 前 燕,

Jiù shí wáng xiè táng qián yàn,

飞 入 寻 常 百 姓 家。

fēi rù xún cháng bǎi xìng jiā.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Black Clothes Alley Liu Yuxi

Weeds and wildflowers spread by Vermilion Sparrow Bridge;

Setting sunlight slants down Black Clothes Alley's entrance.

Sparrows in olden days at courtyards of Wang and Xie mansions,

Now flitter into ordinary people's humble houses.

* * *

Wuyi Alley 乌衣巷, literally "black clothes alley", is located on the south side of the Qinhuai River 秦淮河 in Nanjing

南京. During the Three Kingdoms period 三国时代 (220 - 280) it was the barracks site of an ancient fortified city - Stone

City - built on a hilltop overlooking the Yangtze River and guarding Nanjing, capital of the state of Wu 吴. The name

"Black Clothes" was chosen because the imperial guard troops at that time always dressed in black. Later the location

became the residence of the rich and powerful Wang Dao 王导 and Xie An 谢安 families during the Eastern Jin Dynasty 东晋

(317 - 420).

Zhuque Bridge 朱雀橋, literally "vermilion sparrow bridge", was the main access over the Qinhuai River between Nanjing

and Black Clothes Alley. There used to be two bronze vermilion sparrows astride the bridge for decorative effect, and

thus the bridge was so named.

Wang Xie 王谢 is a reference to the rich and powerful families led by Wang Dao 王导 and Xie An 謝安. Wang Dao (276 - 339),

a famous statesman, military expert, and calligrapher, was wholeheartedly loyal to the Eastern Jin royal family.

Wang had helped three generations of Eastern Jin emperors establish and stabilize the dynasty during the warring states

era.

Xie An 谢安 (320 - 385), a famous military expert and statesman, won the famous Fei River Battle 淝水之戰 in 383 with 70,000

outnumbered soldiers, decisively defeating Fu Jian's 苻堅 700,000 soldiers. (Fu Jian was also known as the Lord of the

"Former Qin" 前秦 which had nothing to do with the First Emperor, Qin Shi Huang, of the Qin Dynasty in the 3rd century

B.C.) The victory strengthened the position of the Eastern Jin in southeast China and led to the downfall of Fu Jian's state.

After the battle, in order to assuage the Eastern Jin emperor's concern about being possibly usurped by Xie (a not

uncommon occurrence in Chinese history), he voluntarily turned all military power over to the royal family and subsequently

won over the confidence and highest respect of the emperor (in 420, however, a prominent general - Liu Yu 刘裕 - usurped

the throne and ended the Eastern Jin).

By the time Liu Yuxi visited Black Clothes Alley some four hundred years later, the descendants of Wang Dao and Xie

An had long lost and squandered the families' fortune and power, with the halo of noble splendor all but gone, replaced

by the humble tenement dwellings of ordinary people carved out of the once elegant but now dilapidated mansions. Through

Liu's magic brush, the glory of the past was revived and the alley was made famous again. Today, the area is dotted

by very expensive high-end residential units due to the economic boom in China. Indeed, changes and transformations

through the ages are quite unpredictable and can be ironic.

* * *

朱: vermilion, cinnabar 雀: sparrow 桥: bridge, beam, crosspiece 边: edge, margin, side, border 野: wild 草: grass,

straw 花: flower, blossom

乌: black, dark, crow, rook, raven 衣: clothes, clothing 巷口: alley entrance 夕阳: sunset 斜: slanting, sloping, inclined

旧: old, ancient, former, past 时: time, o'clock , period, era, 堂: hall, government office 前: in front, forward, preceding

燕: sparrow

飞入: fly into 寻常: regular, common, normal 百: hundred 姓: surname, one's family name (in Chinese, the family name is

listed first, then followed by the given name) 百姓: ordinary people 家: home, family, house, residence

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Wuyi Alley/Black Clothes Alley was rebuilt in 1993 based upon the architecture of the Ming and Qing styles.

乌衣巷:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

2. The newly reconstructed Vermilion Sparrow Bridge is located on the south side of Nanjing. The exact location of

the original structure has been lost to history. 朱雀橋:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

3. Chinese calligraphy 乌衣巷 书法:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

Liu Zongyuan 柳宗元

Liu Zongyuan (773 - 819; lived in the Mid Tang period) was born in present-day Yongji, Shanxi Province 永济市, 山西省. Around

180 of his poems are extant, of which five are collected in the popular anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems."

"River Snow" 江雪 is his most famous poem.

In 793, at age 20, he passed the imperial examination (see

Tang Poems - Volume 1) obtaining a jinshi degree title. In the same year, Liu Yuxi 刘禹锡, at age 21, (the author

of poem #36 "Black Clothes Alley") also passed the imperial exam. The two young men went on to form a solid, lifelong

friendship. In 798, Liu Zongyuan passed an advanced imperial examination and started his civil service career right

way in the capital of Chang'an.

His civil service career was initially successful. But in 805, when the new Emperor Li Song 李诵 ascended the throne,

Liu joined the Yong Zhen Ge Xin 永贞革新 reform movement to rectify corruption and curtail the military and political power

of the eunuchs (see

Tang Poems - Volume 1) and frontier peoples in order to help the new emperor to solidify central government power.

The movement was in direct conflict with the eunuchs and soon Emperor Li Song, in reign for only one year, was forced

by the eunuch faction to abdicate in favor of Prince Li Chuen 李纯; Li Song died within a year. The leader of the movement

- Wang Shuwen 王叔文 - was executed at age 47 by the puppet Emperor Li Chuen 李纯. That spelled the end of the reform

movement, which lasted for only 146 days.

At the same time, major movement advocates, such as Liu Zongyuan 柳宗元 and his good friend Liu Yuxi 刘禹錫, as well as

six others, were banished to various remote areas of the country. Liu Zongyuan was banished first to Yongzhou, Hunan

Province 永州, 湖南省 as a Sima 司马 (a low position usually reserved for exiled officials with low pay and no power) for

ten years. In January 815 he was recalled back to the capital of Chang'an. After a month of arduous travels, he arrived

in Chang'an in February. Then almost immediately thereafter in March he was re-banished to Liuzhou, Guangxi Province

柳州, 广西省 due to further political intrigue. After living in bleak and desolate conditions for four years, he was placed

on yet another state amnesty list in 819 for repatriation back to Chang'an. Before the imperial edict arrived, however,

he died in Liuzhou, leaving behind his pregnant wife and three young children. He had led a tough life of intermittent

banishment during his prime and died at age 46.

Exile, however, allowed him to spend more time studying and working on philosophy, history, politics, and literature.

He thus produced a great many poems, essays, fables, political commentaries, and reflective travelogues during this

period.

Along with Han Yu 韩愈 (768 - 824), he was an initial promoter of the Classical Prose/Guwen Movement 古文运动 which

advocated clarity and colloquialism in describing subject matter. It was a reaction against "Piantiwen" 骈体文, which

was informed by pomposity and restrictive structures.

The Eight Great Prose Masters of the Tang and Song were:

Han Yu (韩愈; Tang Dynasty),

Liu Zongyuan (柳宗元; Tang Dynasty),

Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修; Song Dynasty),

Su Shi (苏轼; Song Dynasty),

Su Xun (苏洵; Song Dynasty),

Su Zhe (苏辙, father of Su Shi and Su Xun; Song Dynasty),

Wang Anshi (王安石; Song Dynasty), and

Zeng Gong (曾巩; Song Dynasty).

#37 River Snow 江雪

Traditional Chinese

江雪 柳宗元

千山鳥飛絕,萬徑人蹤滅。

孤舟簑笠翁,獨釣寒江雪。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

江 雪 柳 宗 元

Jiāng xuě liǔ zōng yuán

千 山 鸟 飞 绝, 万 径 人 踪 灭。

qiān shān niǎo fēi jué, Wàn jìng rén zōng miè.

孤 舟 蓑 笠 翁, 独 钓 寒 江 雪。

gū zhōu suō lì wēng, dú diào hán jiāng xuě.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

River Snow Liu Zongyuan

Across a thousand mountains,

Have the birds all away flown;

The myriad tracks of human

footprints,

Have all away blown.

In a solitary skiff,

Is dressed an old man in straw,

On the icy river,

Angling in snow all alone.

* * *

Liu wrote this poem during his difficult exile. With a peaceful mind and sense of self-cultivation, he transformed his grief

into this artistic conception - tranquil, peaceful, and self-possessed - a true reflection of zen 禅 thought.

This "pictorial" poem has been attracting the attention of great many a painters since the Tang Dynasty, yet none

has been able to quite capture and express the exceptional tranquility and profoundness embedded within the verses.

It is, indeed, an exquisite poem.

* * *

江: river 雪: snow

千: thousand, a great many 山: mountain 千山: hundreds of mountains 鸟: bird 飞: to fly 绝: to vanish, to cut

short, extinct, to disappear, by no means, absolutely

万: ten thousand, a myriad, a great many, a great number 径: footpath, track 万径: thousands of footpaths/tracks

人: man, person, people 踪: footprint, trace, tracks 灭: to extinguish or put out, to go out (of a fire, etc.), to

exterminate or wipe out

孤: lone, lonely 舟: boat 蓑: raincoat made of straw or coir 笠: rain hat made of straw, coir, or bamboo 翁: elderly man

独: alone, single, sole, only 钓: to fish with a hook and bait , angle 寒: cold, poor, to tremble, chilly, chilling,

cool, frigid, chill, icy 江: river

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Straw cape 蓑衣:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

2. Rain hat made by straw or bamboo 斗笠:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

3. Chinese calligraphy 江雪 书法:

view thru Google or

Yahoo.

Li Shen 李绅

Li Shen (772 - 846; lived in Mid and Late Tang periods) was born in Huzhou, Zhejiang Province 湖州, 浙江省 Zhejiang Province. When he was five years old, his father passed away.

He excelled in literature and poetry, yet none of his poems are included in the popular anthology "Three Hundred

Tang Poems."

After passing the imperial examination at age 27 (see

Tang Poems - Volume 1) and obtaining a jinshi degree title, he was assigned an assistant professor position at

the Imperial Educational Institute (an organization responsible for educating the young male members from the royal

family) and later eventually was made a member of the highly prestigious Hanlin Academy 翰林学院 (see

Tang Poems - Volume 1). Not long after he started his professorship, he was re-assigned as a remonstrate official

Youshiyi (see

Tang Poems - Volume 1) and worked his way up.

During his career, he became deeply involved in the Niu-Li Factional Struggles 牛李党争 (808 - 846) and was the right

hand man of Li Deyu 李德裕, leader of the Li Faction, whose supporters were officials of largely aristocratic origins.

The opposing Niu Faction was led by Niu Sengru 牛僧孺, and was composed of officials from humble origins. The Niu-Li Factional

Struggles brought the already weakened Tang into further disarray. In the latter years, Both Li and Niu factions were

forced to work hand in glove with eunuchs to carry out their plans. Carefully maneuvering the treacherous path to power, Li Shen eventually became prime minister at age 70, dying four years later at age 74 in 846.

Soon thereafter, the capital case of Wu Xiang 吴湘 was appealed by Wu Xiang's brother against Li Shen. The new Emperor

Li Chen 李忱 ordered a re-investigation of the matter, which determined that Wu Xiang had been improperly executed at

the hands of Li Shen and Li Deyu. As a result, Li Shen was posthumously stripped of three honorary titles and Li Deyu

was demoted and exiled to Hainan Island 海南岛. Li Deyu eventually died on Hainan in 850 at age 63 (the opposition leader,

Niu Sengru, had died at home in 848 at age 69). Thus ended the nearly 40 year long Niu-Li factional struggles.

Sun Zhu 孙洙, the compiler of "Three Hundred Tang Poems", did not include any of Li Shen's poems in his anthology

- not even the popular "Sympathize with Farmers (1)" and "Sympathize with Farmers (2)". It might have been that Sun

Zhu perceived Li Shen as being corrupted by power and lacking in moral character due to the latter involvement in

Wu Xiang's wrongful execution.

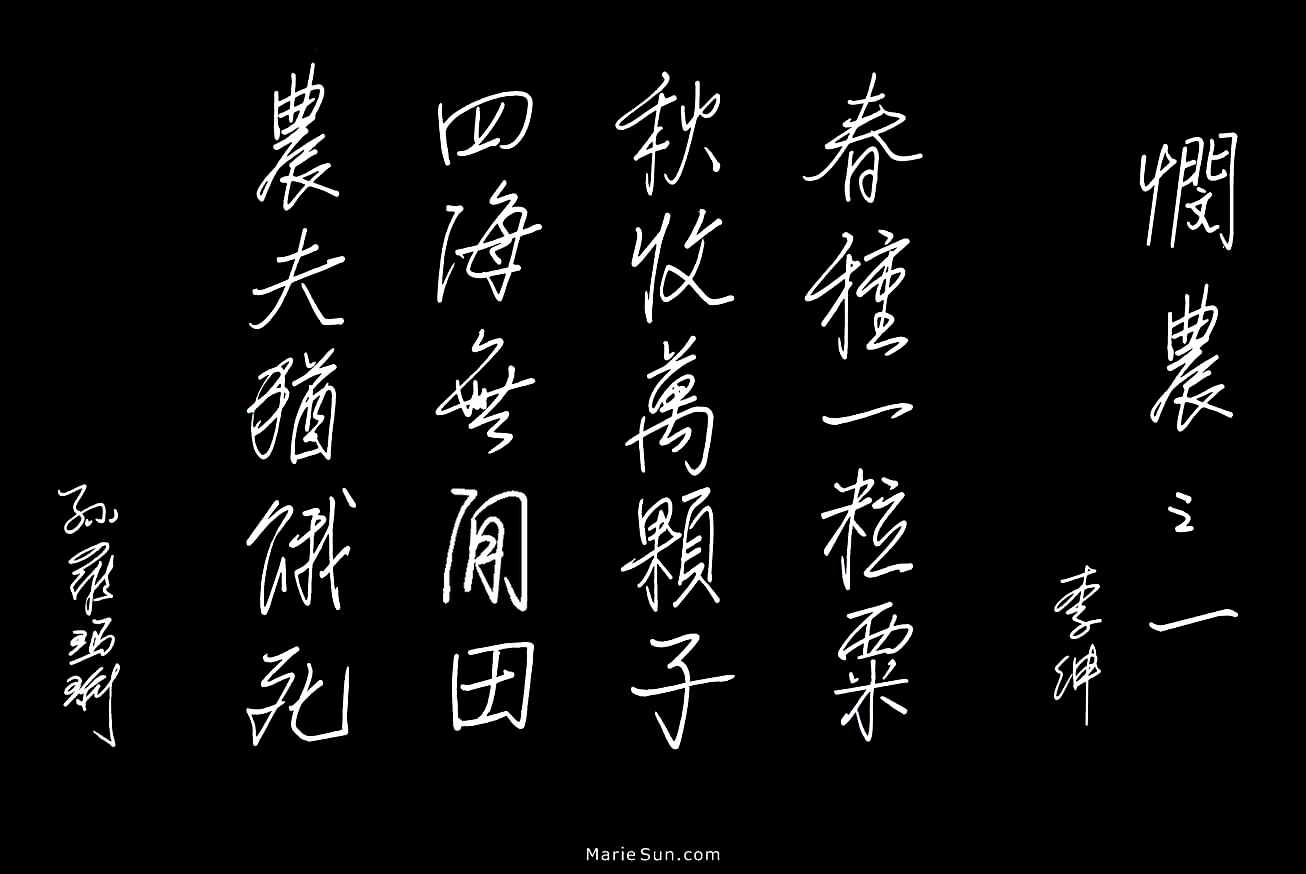

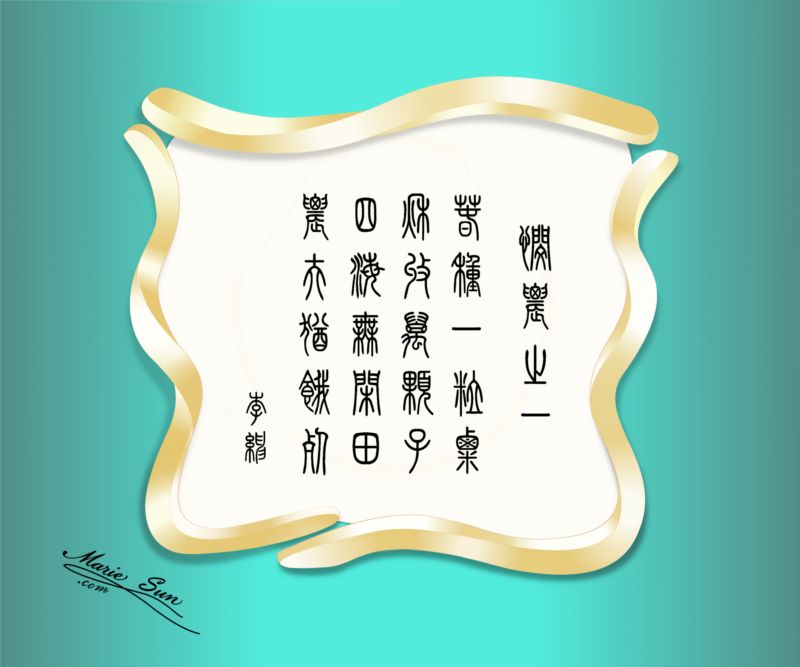

#38 Sympathy for Farmers (1) 悯农 (一)

Traditional Chinese

憫農 (一) 李紳

春種一粒粟,秋收萬顆子。

四海無閑田,農夫猶餓死。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

悯 农 (一) 李 绅

mǐn nóng (1) lǐ shēn

春 种 一 粒 粟, 秋 收 万 颗 子。

chūn zhòng yī lì sù, qiū shōu wàn kē zi.

四 海 无 闲 田, 农 夫 犹 饿 死。

sì hǎi wú xián tián, nóng fū yóu è sǐ.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

correction on recitation 1: 春种一粒粟, "种" in here should be pronounced as 种 zhòng (plant, sow seed) instead of 种 zhǒng .

Sympathize with Farmers (1) Li Shen

A grain of millet sown in the spring,

Leads to a harvest bounty by the fall.

Under the sky, no idle fields lie,

Yet peasants succumb to starvation's pall.

* * *

The two "Sympathize with Peasants" poems were written by Li Shen before he rose to power. During his official career

as prime minister, there were no records of any policy that he may have ever carried out on behalf of the peasants.

Most of his time and effort was apparently devoted to struggles for political power and wealth, ending in corruption

and criminal involvement in a wrongful death case. Despite his apparent immorality, these two poems truly spoke on

behalf of the disadvantaged, hard-laboring, and struggling peasantry.

* * *

悯: sympathize with, pity, grieve for 农: farmer, peasant, agriculture, farming

春: spring, joyful, youthful, love, lust

Two ways to pronounce 种:

(1). zhòng - to plant, to grow, or to cultivate something. Such as to plant trees 种树 [zhòng shù], plant flowers 种花

[zhòng huā]

(2). zhǒng - seeds 种子 [zhǒng zǐ], species 种类 [zhǒng èi], race 种族 [zhǒng zú]

一: one, 1, single 粒: grain, granule, classifier for small round things (peas, bullets, peanuts, pills, grains, etc.)

粟: millet, grain

秋: autumn, fall 收: collect 秋收: fall harvest, to reap 万: a myriad, a great number, ten thousand, thousands and thousands 颗: a

grain, a drop or droplet, a pill, a bead 子: seed, son, child

四: four 海: sea, ocean 四海: all over the world, under the sky 无: not to have, no, none, not, to lack, un- 闲: to stay

idle, to be unoccupied, not busy, leisure 田: agricultural land, cultivated land, rice-field, field

农夫: farmer, peasant 犹: yet, as if, (just) like, just as, still 饿: to be hungry, hungry 死: die, to die

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Farmers working at millet or rice fields in China:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

2. Chinese calligraphy 春種一粒粟书法:

view thru Google or

Baidu.

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

... omitted

...

...

...

...

...

...

3. Empress Wu Zetian - Promoter of Tang Poetry

Wu Zetian 武则天, the only female emperor in Chinese history and grandmother of Tang Ming Huang, was another Tang poetry promoter, second only to grandson.

During her reign (690 - 705), She opened the door for more commoners to take the imperial exam which was a stepping stone for entry into the civil service. Poetry was included on the jingshi degree title exam (this was initialized by the second Tang Emperor, Li Shimin, to whom Wu Zetian served as one of his many consorts) which incentivized people to appreciate the value of poems. While on throne, she often held poem appreciation contest parties to entertain her officials. By the time Tang Ming Huang landed on throne in 712, chanting and composing poems had already come into fashion in Tang society, for which Wu Zetian is to be credited. Li Bai's poem "Presentation to Wang Lun" "赠汪伦" describes this popular trend of chanting poems.

* * *

Wu Zetian was born into a well-to-do family in Chang'an. Her father, Wu Shiyue 武士彠,

was a successful businessman in the lumber business and her mother, Yangshi 杨氏, was a royal family member from the previous

Sui Dynasty of

* Xianbei 鲜卑 ethnic lineage. Wu Shiyue, with sharp insight, financially aided Li Yuan 李淵, a general of the Sui 隋 dynasty, who then overthrew Sui in 618 and became the first emperor of the Tang. Consequently,

Wu Shiyue was rewarded with a succession of senior ministerial posts, including governor of Yangzhou 扬州 (the most prosperous city at the time in the Jiangnan region) and other cities.

In 626, Li Yuan abdicated the throne in favor of his second son - Li Shimin 李世民. Eleven years later, Li Shimin, at age 39, called in Wu Zetian, then 13 years of age, attractive and bright, to be one of his consorts and conferred upon her the title of Cairen 才人, which was rank five in the consort system, with rank one being the highest and eight (or nine at various times) the lowest. To be inducted as a consort of the powerful Tang emperor was a point of great pride to any family, let alone being inducted immediately at rank five. Even so, it might not yet have been a young girl's dear mother's wish. Her mother, Yangshi, worried deeply on the day of her little daughter's departure for the imperial court - a strictly guarded "forbidden palace." Zetian comforted her mother attentively, said goodbye to her siblings (two elder

half-brothers and an elder sister; her father had died two years earlier), and with a positive attitude she stepped into her uncertain future still, essentially, a child. During the Tang, by law (Tang Code/Tang Lu 唐律 -

Wikipedia) males and females were allowed to get married at age 15 and 13 respectively. The main reason was that the average human life expectancy was short in ancient times. It was also thought to guarantee a more secure and stable old age, if one "started early."

When Wu Zetian was a little girl, she was home schooled by her long-since sinicized mother. Home schooling for girls in noble and literati families had always been common in China, and not just a trend in the Sui and Tang dynasties. And the task was usually handled by the mother. After she entered into the imperial back court (royal court harem), Zetian read extensively, due to the interest in books fostered by her mother.

Not much was recorded of her time as consort to Emperor Li Shimin - one of the more capable emperors of the Tang Dynasty. Twelve years after she entered the palace, Emperor Li Shimin died at age 51. According to court rules, consorts who had not produced any children were to be permanently confined to a royal convent after an emperor's death. Wu, who was 25 and had borne no child, was consigned to Ganye Temple 感業寺 - a Taoist convent run by the royal family in Chang'an, with the expectation that she would spend the rest of her life there living as a Taoist nun.

While attending the first year anniversary ceremony at the convent marking the passing of the former emperor, the new 22 year old Emperor Li Zhi 李治 (the 9th son of Li Shimin) met Wu again at the temple. Observing that there was affection between the two, Empress Wang suggested

her husband bring Wu back to court to be his consort. The empress hoped that Wu would replace consort Xiao Shufei 萧淑妃, Wang's rival.

After remaining in the convent for two years and completing the ritual services for the deceased Emperor Li Shiming, she returned to the the imperial court, already pregnant with the new emperor's child. After arriving at the palace, she began to pursue with a single-minded determination, the grabbing and amassing of power and the taking of control of her own destiny by her own hands.

Wu - attractive, wise, and exceptionally gifted - soon became the apple of the emperor's eye and his favorite among all the consorts.

....

....

....

....

During her reign, she flung the doors of the imperial examination system wide open to

previously disqualified social classes and leveled the playing field for entering the imperial civil service. Wu also initiated a policy of attending the jinshi degree title imperial exam in person and interviewing the jingshi

degree title-holders after the exam, personally in court. At the same time she increased the head count of jinshi degree title holder positions and hired and promoted capable jingshis and scholars to high positions regardless of birth background. These policies motivated commoners to pursue education in almost all levels of society and helped to reduce the power of the aristocracy. She thus gained the allegiance of her countrymen and consolidated her power.

On the military side,

she founded the military imperial examination, known as the Wuju 武举, .......

....

....

During her rule, including during the latter portion of her husband's reign, she dedicated herself to improving the position of women by issuing decrees to protect women's rights, such as a woman's right to marry, re-marry, divorce, contest a divorce, etc. She even modified the right of inheritance to some degree to provide more protection for women. During her reign, women enjoyed a higher social status than at any other point in pre-modern Chinese history. Wu Zetian could be considered the first women's movement activist.

Cultural background and integration played an important role in this issue. In contrast to the Han females being bound by rigid Confucian ethics and restrictions,

Wu Zetian, with her *Xianbei background, was more aggressive, bold, and creative.

These qualities greatly helped Wu break out from under a male

dominated world to emerge as the first (and extremely powerful) female emperor in Chinese history.

That is, until 705,....

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

...

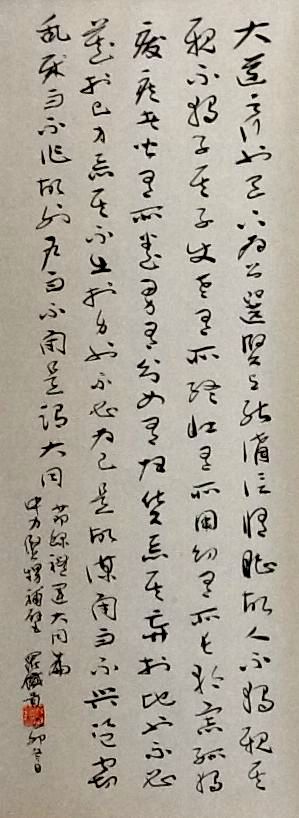

(4). In memory of Mr. Luo Tie-ching and Ms. Ma Wu (United by Marriage and Love), Parents and Grandparents of the Authors.

记念罗铁青先生及马勿女士

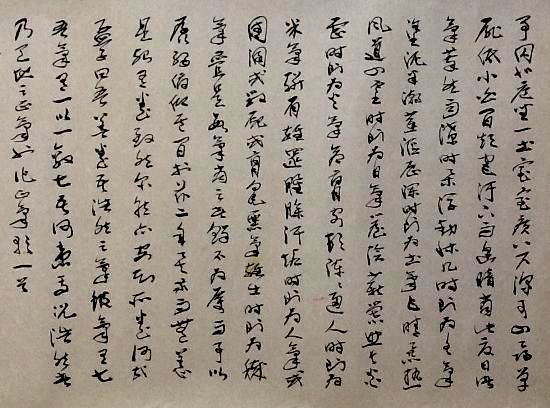

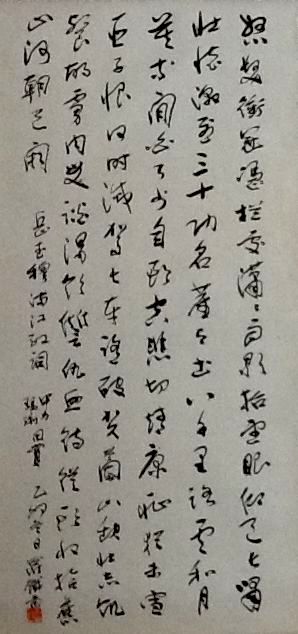

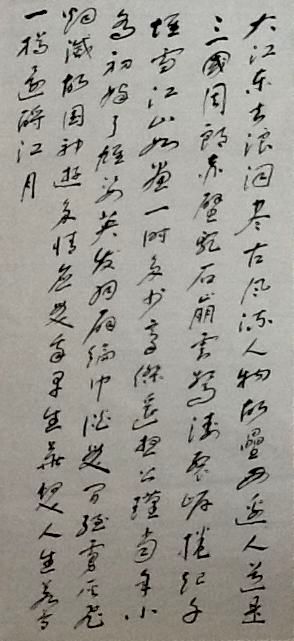

Calligraphy by Mr. Luo Tie-ching 罗铁青先生书法:

礼运大同篇:

岳飞 - 满江红:

苏轼 - 念奴娇·赤壁怀古:

海纳百川有容乃大; 壁立千仞无欲则刚.

截錄自 - 文天祥 正气歌 :

截錄自 - 范仲淹 岳阳楼记:

文天祥 - 正气歌:

Calligraphy by Ms. Ma Wu:

7.

...

....

8.

....

...

9.

...

....

10. About the Authors

Marie Sun and Alex Sun (mother and son)

Marie Sun/孙罗玛琍:

Marie was born in mainland China and moved to Taiwan with her family in 1949. She grew up in Taiwan and

graduated from National Taiwan University in 1965, majoring in economics.

She immigrated to the U.S. in 1968 and worked in the computer programming field for various companies, including

IBM, retiring in 1992. In addition to computers, she has always had a passion for Chinese poetry, calligraphy,

and painting.

Alexander Sun/孙国強:

Alex was born in the U.S.. At age 12, he was invited by his dear grandparents, Mr. Teiqing Luo and Ms. Wu Ma, in Taipei, Taiwan to study Chinese and experience Chinese culture for a year.

He went on to attend Georgetown University in the U.S., graduating from the Law School in 1992 and becoming a lawyer. While at Georgetown University, he also spent a year studying political science at Beijing University in Beijing, China from 1990 to 1991, and revisited and traveled around the country in later years.

Alex's natural interest in learning different languages, cultures and exploring his roots proved an immeasurable help in producing this book.

11. Share with Media

Thank you for reading.

We invite you to share your thoughts with your friends -

All rights reserved ©www.mariesun.com

Last updated: 2020 01 24 by Marie Sun

All following 4 pgms are covered by

000_all/pov0_indexbar_2_main folder

for indx ------------ /pov0_indexbar_main/web_SHORT_2_indx_ebook.html

for body ------------ /pov0_indexbar_main/web_SHORT_2_home_ebook.html

for header ------------/pov0_indexbar_main/web_SHORT_2_frame_header_po.html

for right section -----/pov0_indexbar_main/web_SHORT_2_indexbar_on_right_ebook.html

![]() Calligraphy images referred by the book

may be freely copied from this website

for educational or noncommercial positive purposes (i.e., no gambling or pornography, etc.) with an attributional reference to "Marie Sun and Alex Sun or at MarieSun.com" ; other uses require explicit, written authorization by Marie Sun.

Calligraphy images referred by the book

may be freely copied from this website

for educational or noncommercial positive purposes (i.e., no gambling or pornography, etc.) with an attributional reference to "Marie Sun and Alex Sun or at MarieSun.com" ; other uses require explicit, written authorization by Marie Sun.