Home

eBook (2) Marie only

Tang Poems ---

(volume 1)

25 top Tang Poems of the Tang Dynasty by 10 poets

Annotated with Chinese historical references and explanations

|

Authors: Marie L. Sun and Alex K. Sun

孙罗玛琍, 孙国強

(Mother and Son)

This eBook is published by

www.amazon.com

Authors' website:

www.mariesun.com

Twitter:

@mariesun88yes

(last updated on 2019/06/16: on

"去美亚买书指南" --- How to purchase this book on www.amazon.com )

The calligraphy images in the book may be freely copied/screen snapshot

for educational or noncommercial purposes and uses of a legitimate nature (i.e., no gambling or pornography, etc.) with an attributional reference to "Marie Sun and Alex Sun" or "at MarieSun.com"; other uses require explicit, written authorization by Marie Sun or Alex Sun.

The calligraphy images in the book may be freely copied/screen snapshot

for educational or noncommercial purposes and uses of a legitimate nature (i.e., no gambling or pornography, etc.) with an attributional reference to "Marie Sun and Alex Sun" or "at MarieSun.com"; other uses require explicit, written authorization by Marie Sun or Alex Sun.

|

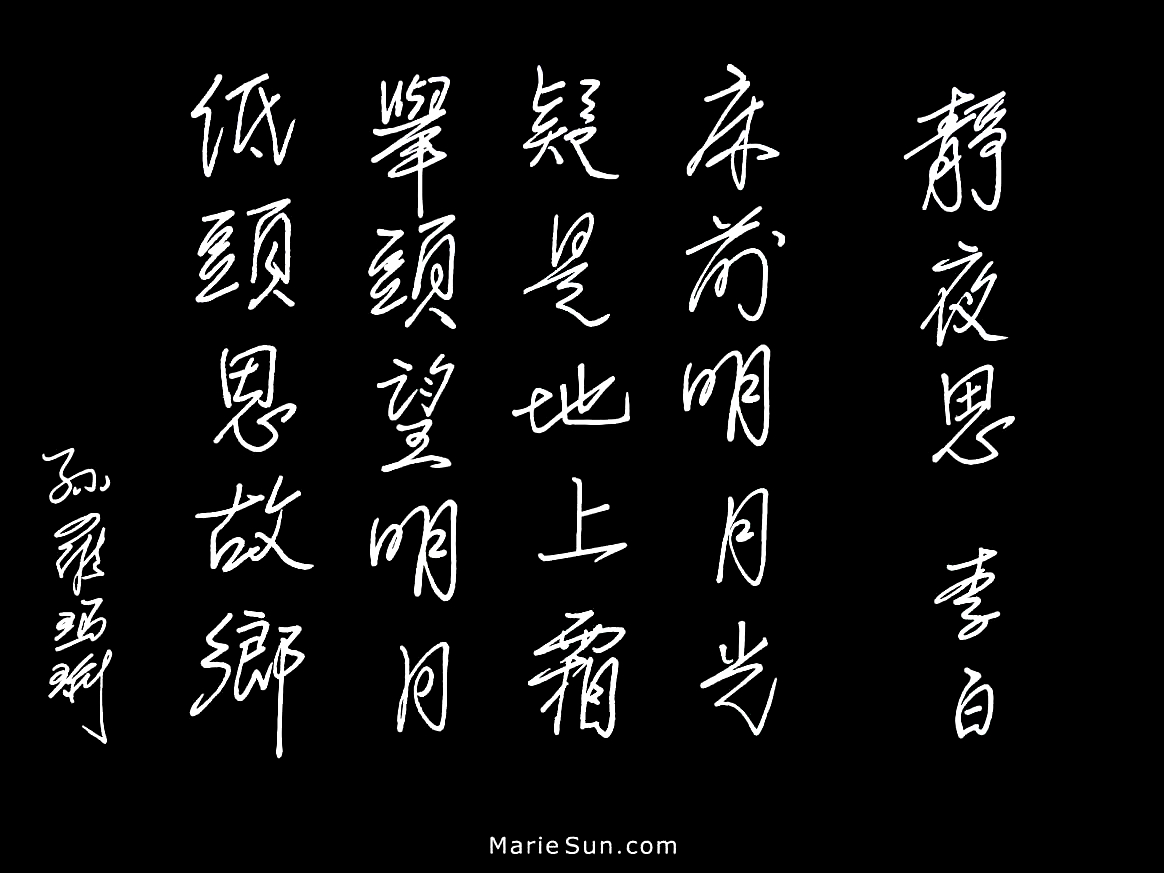

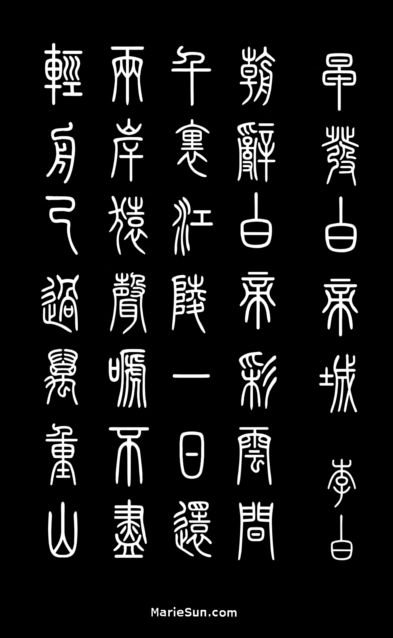

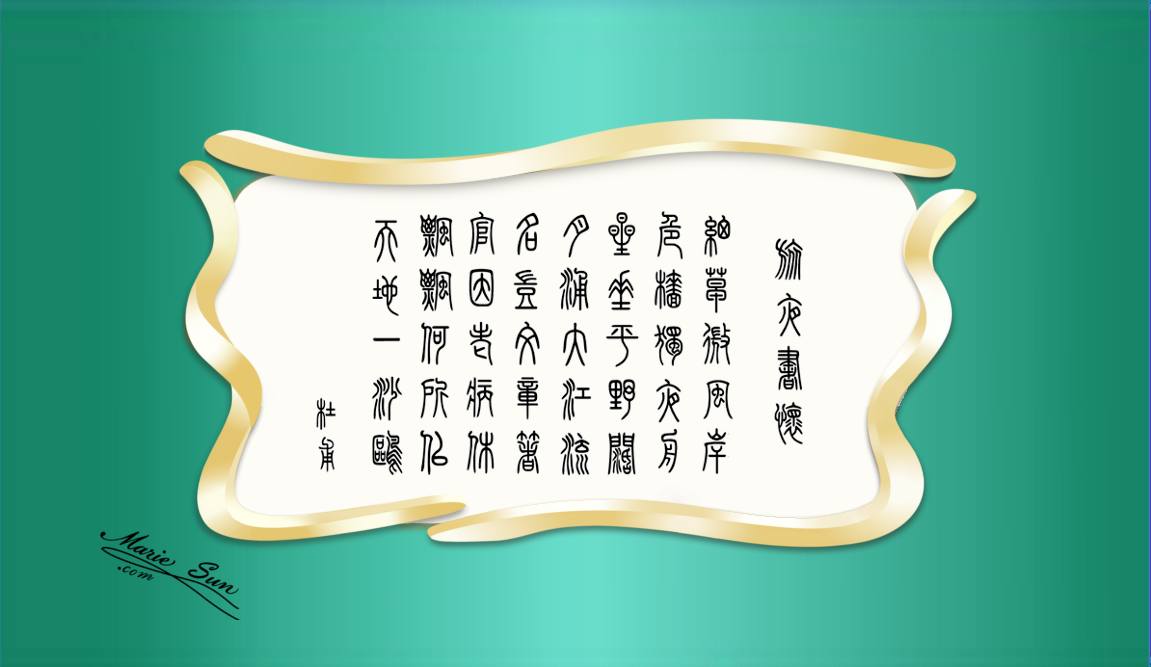

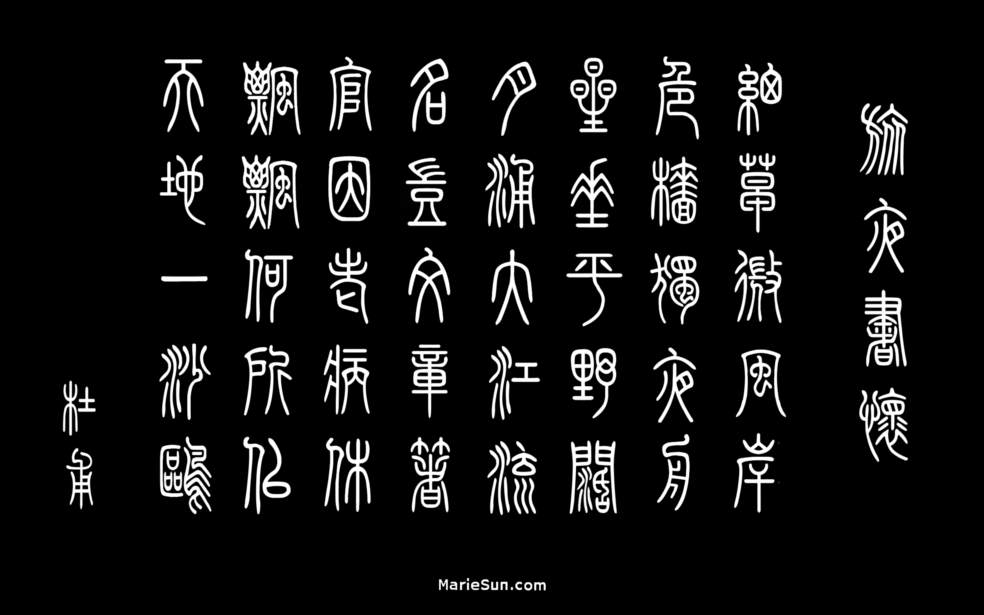

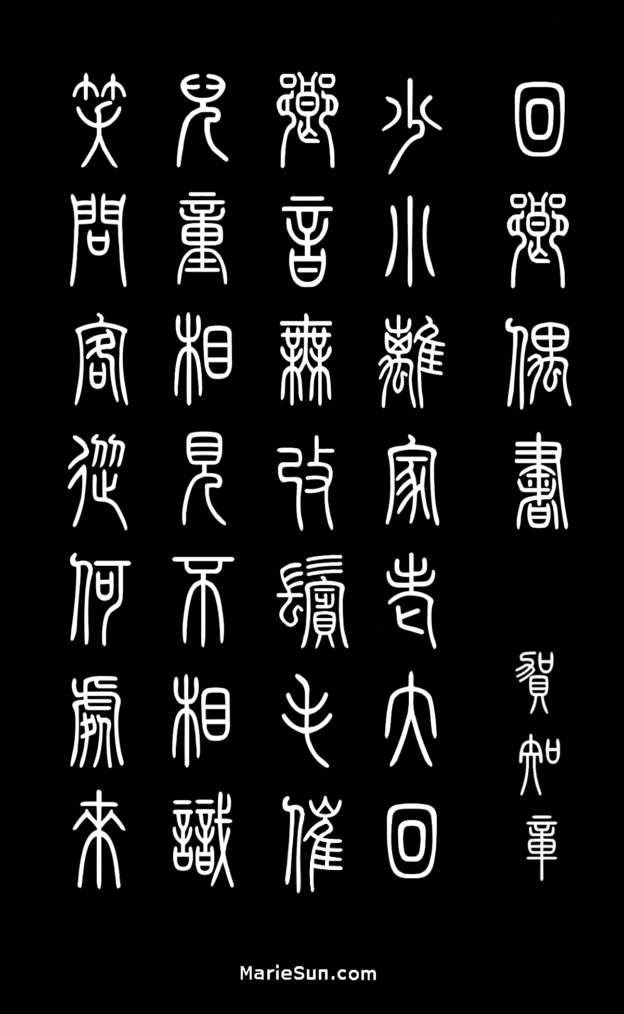

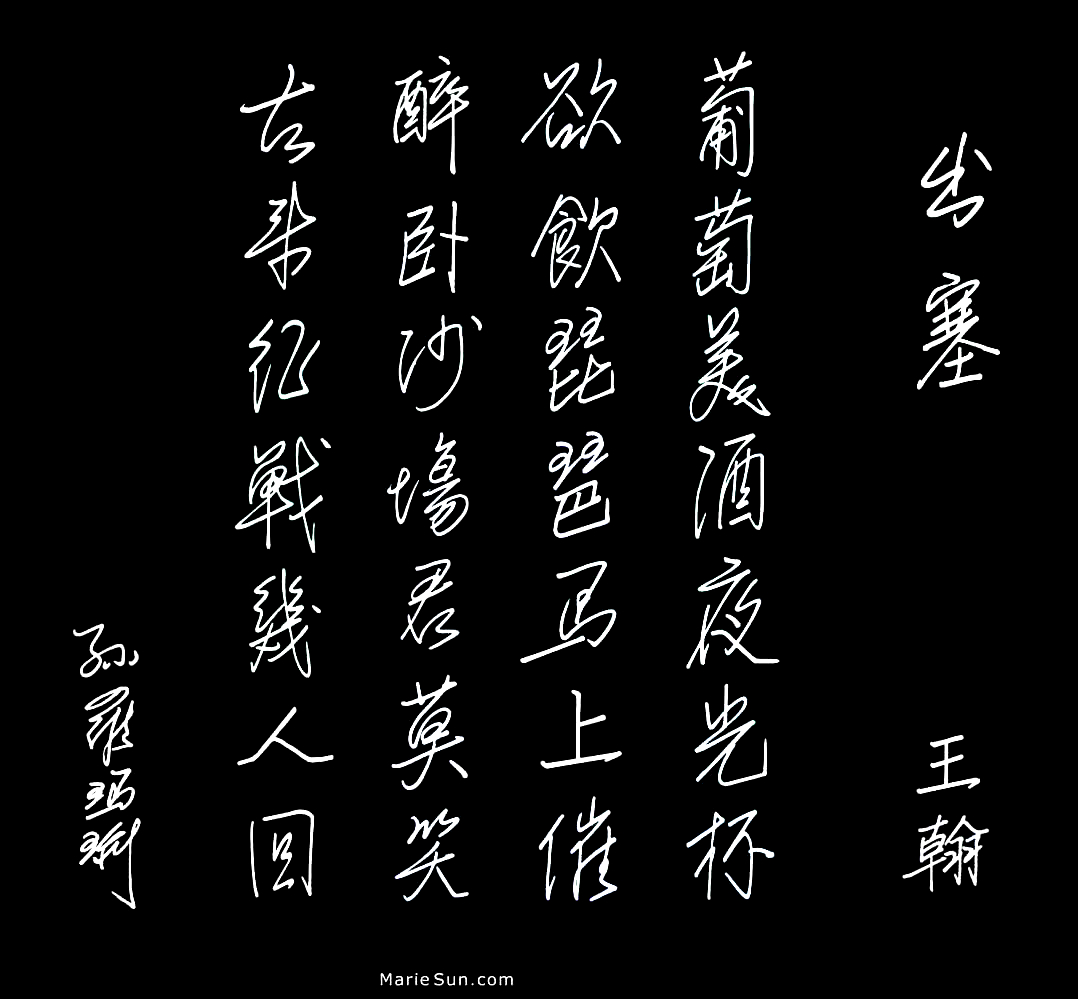

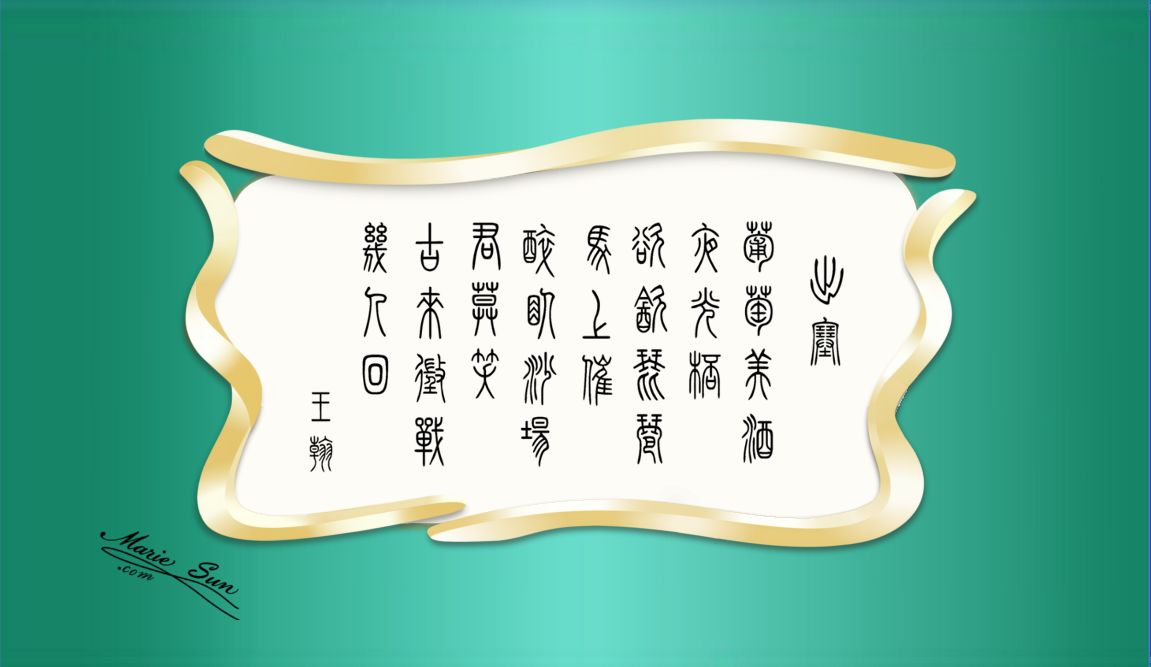

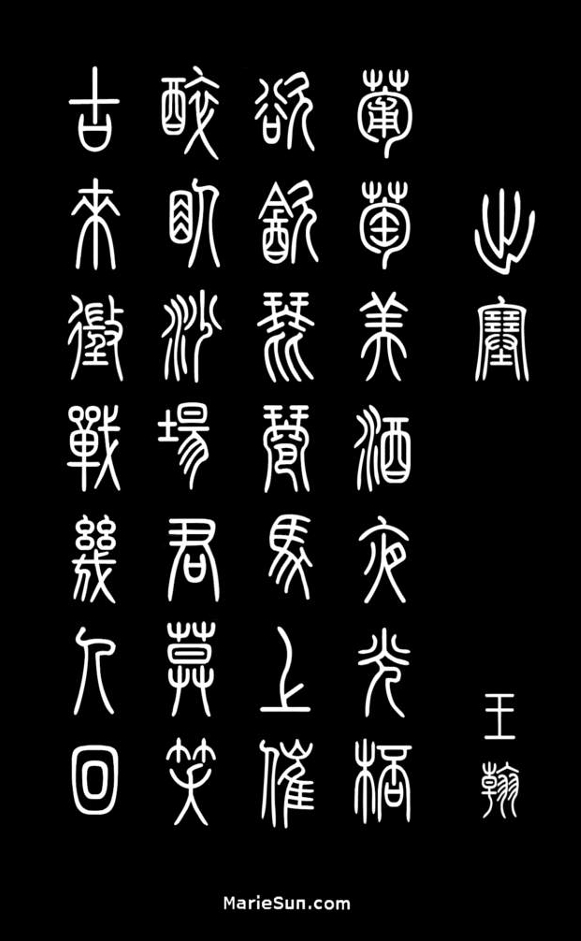

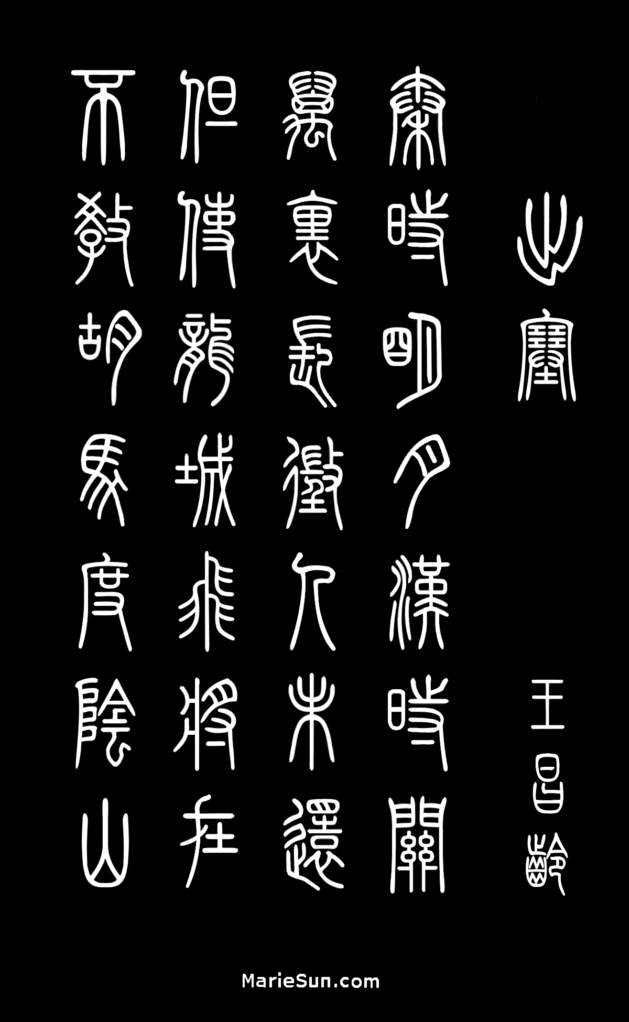

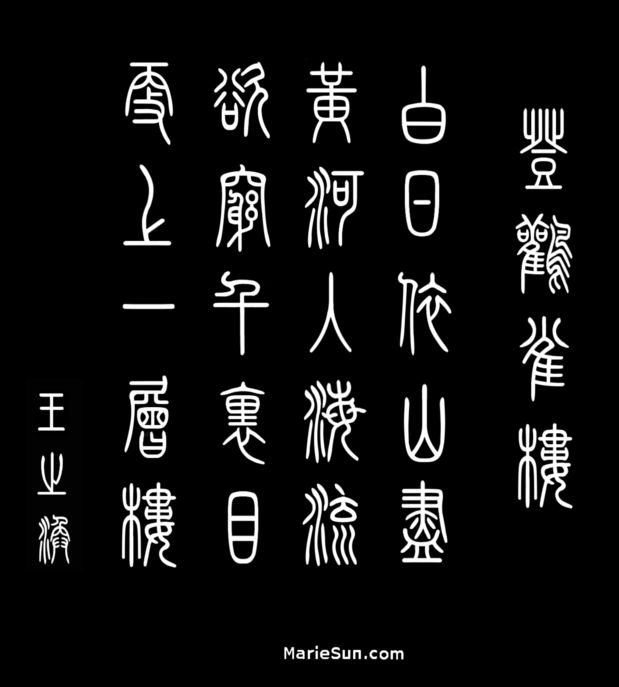

12 of the poems are presented with zhuanshu/zhuanzi calligraphy (see above) and the rest xingshu calligraphy.

|

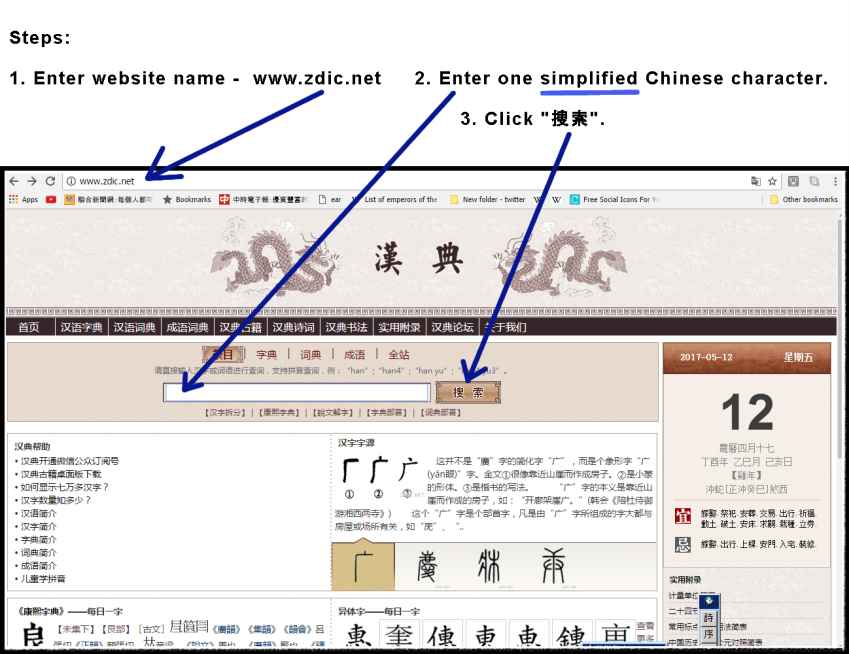

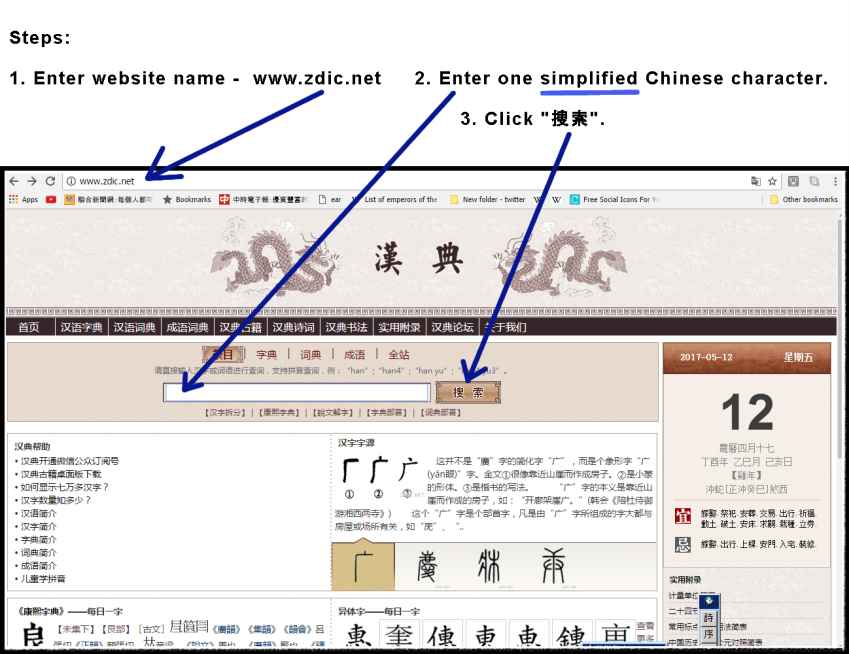

Tips: For beginners on how to purchasing kindle books: Tips: For beginners on how to purchasing kindle books:

Here is

the easiest way to purchase yourst kindle book, including “Tang Poems” or any other book at the US Amazon store and read it on your PC, Laptop, Mac, iPhone, iPad, Android phone, etc. You don’t even have to download any Kindle Applications or purchase any Amazon Kindle Readers/devices. It also provides special instructions for people located in China or certain other foreign countries. The book is published at Amazon.com.

|

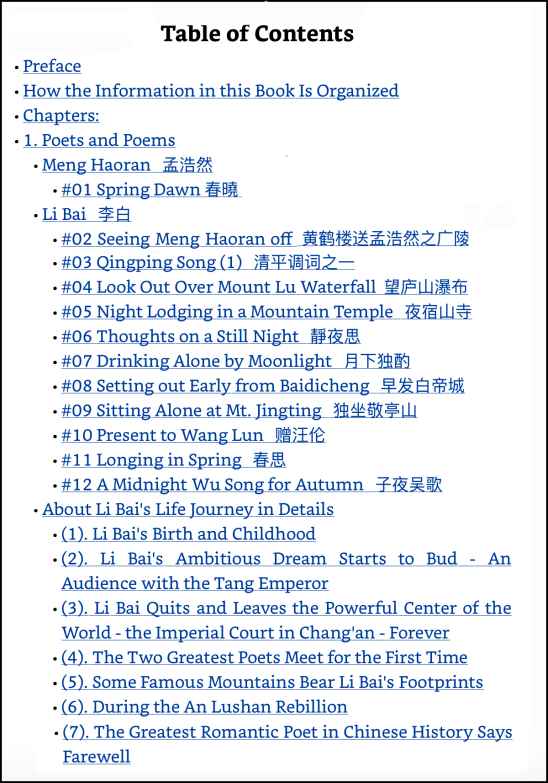

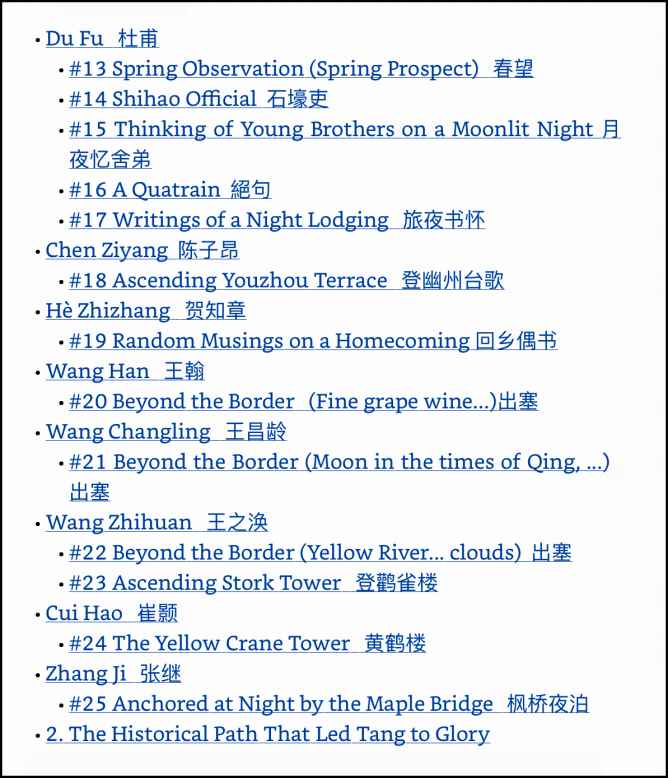

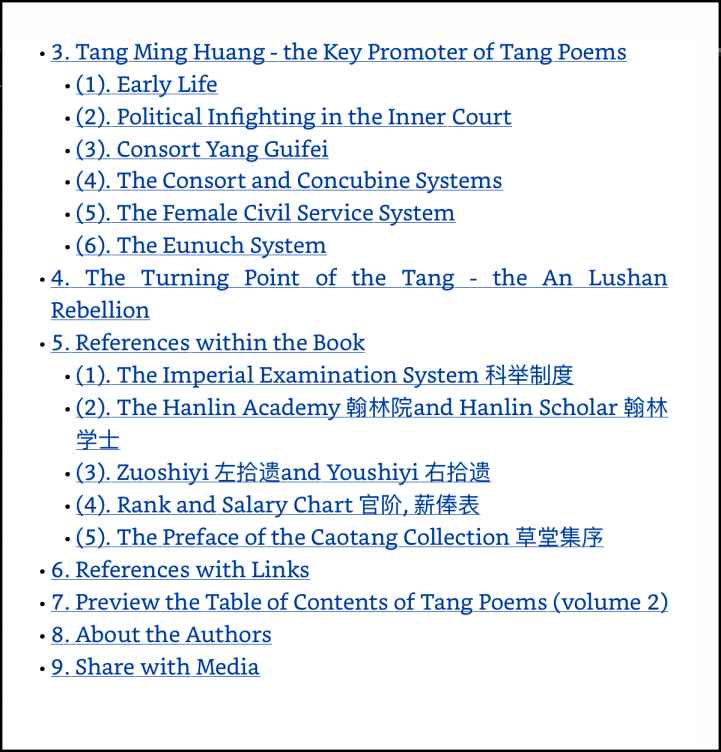

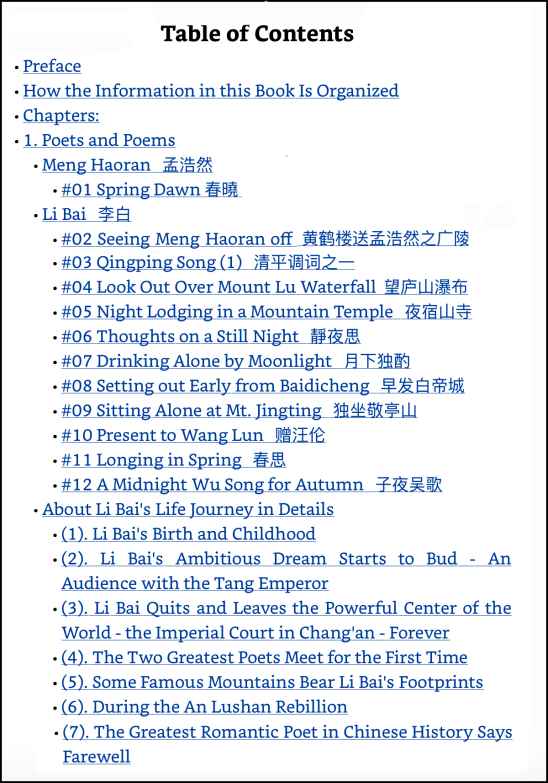

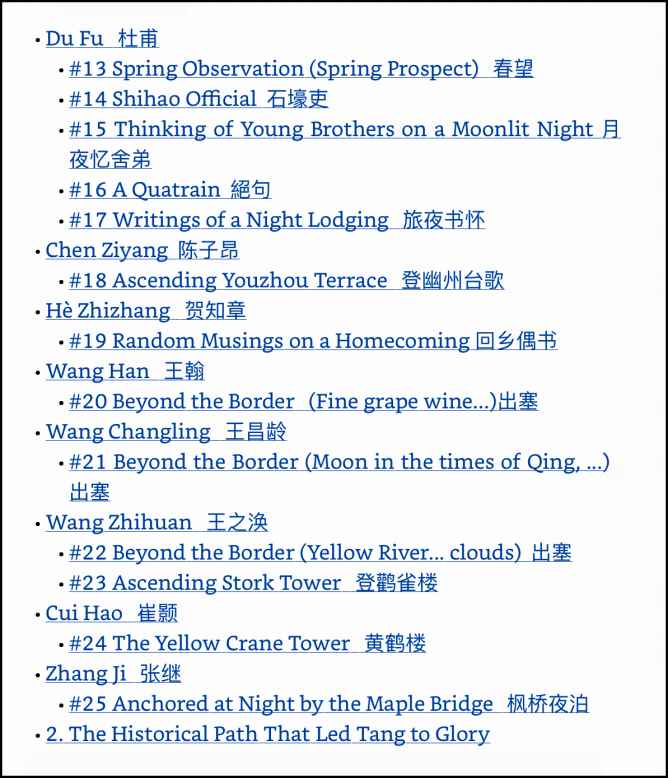

Preview Table of Contents

Preface

This book

is an expanded edition of

25 Tang Poems (volume 1). It

is dedicated to the memory of Marie's dear parents, Mr. Tieqing Luo and Ms. Wu Ma, who inspired Marie's early interest in and appreciation of Tang poetry and Chinese calligraphy.

The book is structured differently from any other book on Tang poetry. Rather than simply providing a translated poem in isolation, it provides in-depth historical and cultural background information surrounding the poem, accompanied by multimedia links to maps, images, and/or videos scripts, including recitations in Mandarin for each of the 25 poems. In this way, the reader can more fully understand and appreciate all the nuances of the poem in its Chinese cultural context.

In particular, this book provides information regarding

Tang era social structures, key turning points relating to the rise and fall of the Tang Dynasty, and the political machinations of imperial court life -- all of which informed the narrative of Tang poetry.

Of particular note is one singularly key figure of the Tang era -- Emperor Tang Ming Huang, who promoted poetry during his reign and led to its Golden age in Chinese history.

In keeping with the old adage that "a picture is worth a thousand words," image/video links are provided from time to time to accompany a poem to help put it in context:

The Great Wall thru Google,

Section of Silk Road in the desert thru Yahoo,

Hanging coffin thru Baidu, and

Installing coffin on towering cliff face thru YouTube, etc.

After more than 1,000 years of weather and war, the structures above may no longer retain all of their original glory, yet they still hint at the grandeur of a bygone golden era.

When translating Tang poems into English, the poems' forms, cadences,

and rhyming schemes are naturally difficult to replicate precisely.

This book attempts to retain the poems' original charm, flavor, and

soul, while adhering as closely as possible to those original forms,

cadence, and rhyming schemes.

The beauty of Tang poems is that they can evoke precise visions in an efficient conservation of words, forged into a euphonious stream of rhyme and cadence. These poems represent, and are witness to, archetypical human emotions and pondering reflecting the glory, passion, and tears of a unique era in Chinese history.

If you are not familiar with the history of the Tang, I encourage you to first read

Chapter 2 - The Historical Path that Led Tang to Glory before continuing with the rest of the book. The mood and subject matter of Tang poetry tended to reflect the relative strength and status of the state, such that a knowledge of the political history of the dynasty will give you more insight into the poetry.

* * *

When translating Tang poems into English, the poems' forms, cadences,

and rhyming schemes are naturally difficult to replicate precisely.

This book attempts to retain the poems' original charm, flavor, and

soul, while adhering as closely as possible to those original forms,

cadence, and rhyming schemes.

The essentialist, ambiguous,

and rhythmic spirit of Chinese poems is often lost in flourished occidental

translations trying to explain and make sense of too much. Chinese poems are often purposely designed to be ambiguous or open to interpretation. For example,

in most cases, there is no overt subject in Chinese poems, though the

first person viewpoint is usually understood. Thus, the subject "I" is

often inserted as the assumed viewpoint in occidental translations.

This book attempts to avoid such assumptions except in the most obvious cases.

I hope you will find pleasure and enjoyment in perusing this book, and that you will engage in interpreting the poems you come across in your own way and share them with your friends.

* * *

The co-author, Alex Sun, was born in the U.S.. At age 12, he was invited by his dear grandparents, Mr. Teiqing Luo and Ms. Wu Ma, in Taipei, Taiwan to study Chinese and experience Chinese culture for a year.

He went on to attend Georgetown University in the U.S., graduating from the Law School in 1992 and becoming a lawyer. While at Georgetown University, he also spent a year studying political science at Beijing University in Beijing, China from 1990 to 1991, and revisited and traveled around the country in later years.

Alex's natural interest in learning different languages, cultures and exploring his roots proved an immeasurable help in producing this book.

An enormous thanks also goes out to Scott Shay, a computer expert and linguist who has authored several college textbook from www.amazon.com/Scott-Shay/e/B002BLS206.

With his help, we have been able to publish our first eBook. Also thanks to Benjie Sun for his editorial help and Chung-Li Sun for his spiritual support.

Copyright

All rights reserved. The scanning, uploading, and/or distribution of this book via the Internet or via any other means without the permission of the authors is illegal and strictly forbidden.

How the Information in this Book Is Organized

This book is divided into several chapters, with the first containing the 25 chosen Tang poems organized by poets. Subsequent chapters provided

further general historical and background information.

In Chapter 1, the following information is provided for each poem:

(1). A brief biography of each poet, except for Li Bai and Du Fu, who are described in more detail, due to their seminal influence in the East Asian poetry world (in addition, there is an entire chapter devoted to Tang Ming Huang, the Emperor patron of poetry).

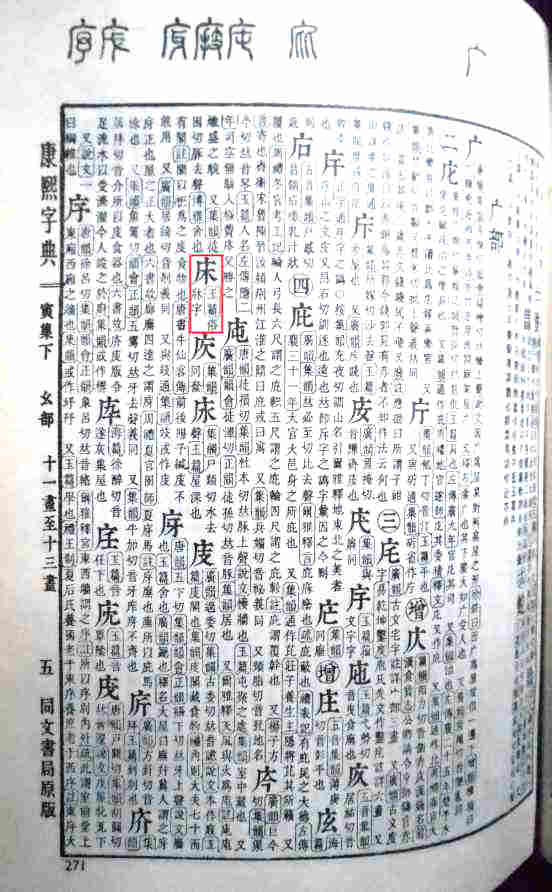

(2). Both traditional and simplified Chinese forms of the poem with pinyin annotations

(3). Recitation in mandarin for each poem

(4). Comments on the historical backdrop of the poem

(5). A glossary of terms and names mentioned in the poem

(6). images or videos relating to the poem or poet

(7). Representation of each poem in xingshu 行书 calligraphy; in addition, 12 poems are also presented in zhuanshu 篆书 calligraphy.

Chapters:

1. Poets and Poems

The following is the concise list of the 25 poems covered in this book that were chosen out of the most popular

Chinese poetry anthology of all time, namely, Three Hundred Tang Poems 唐诗三百首

compiled by Sun Zhu 孙洙 (1711 - 1778).

Most of the poems are presented after a brief biography of the poet. Because of the outstanding status in the poetry world,

extensive background information are provided for Li Bai and Du Fu.

Except for Meng Haoran, Li Bai, and Du Fu, all poets are listed roughly in chronological order, since reading their poems as such allows the reader to follow the historical rise and fall of the the Tang dynasty. Most of the most famous Tang poems, especially the ones related to the frontier, are closely related to the strength of the state. During the empire's early, prosperous years, the frontier poems were full of heroic spirit, such as poem #20 and #21; then during the downward spiral of the latter half of the dynasty, such poems began to reflect a more decadent and depressed mood.

Meng Haoran 孟浩然

Meng Hao'ran (689 or 691 - 740; lived during the Early and High Tang periods), a descendant of Meng Zi 孟子

(also known as Mencius, the famous Confucian philosopher) and grandfather of poet Meng Jiao 孟郊,

was born in

Xiangyang 襄阳 by the Han 汉 River in Hubei Province 湖北省 (Hubei, literally "lake 湖 north 北". The city is located to the north of Dongting Lake 洞庭湖 along the Yangtze River 扬子江/长江).

Meng was a famous landscape poet. Fifteen of his poems are included in the anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems."

He sat for

the imperial examination 科举,

attempting to attain the degree title of "jinshi" 进士 at age 40,

but failed. After his brief pursuit of a career as a local official, he mainly lived in and

wrote about the area in which he was born and raised. The local

landscape, history, and legends were the subjects of his many

poems. So, too, were his journeys.

More than 10 years Li Bai's senior (and Li Bai's idol), he befriended Li in later adulthood. Meng also befriended Wang Wei 王维,

Wang Changling 王昌齡, and Wang Zhihuan 王之涣, among other poets.

Li Bai wrote many poems in admiration of Meng, among which are two famous ones --

"Presentation to Meng Haoran", and

"Seeing Men Haoran off at Yellow Crane Tower". The latter is included in this book.

Meng Haoran, as a prominent

landscape poet, had a major influence on poetry in the Early Tang era. This influence also extended into neighboring Asian countries, especially Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.

* * *

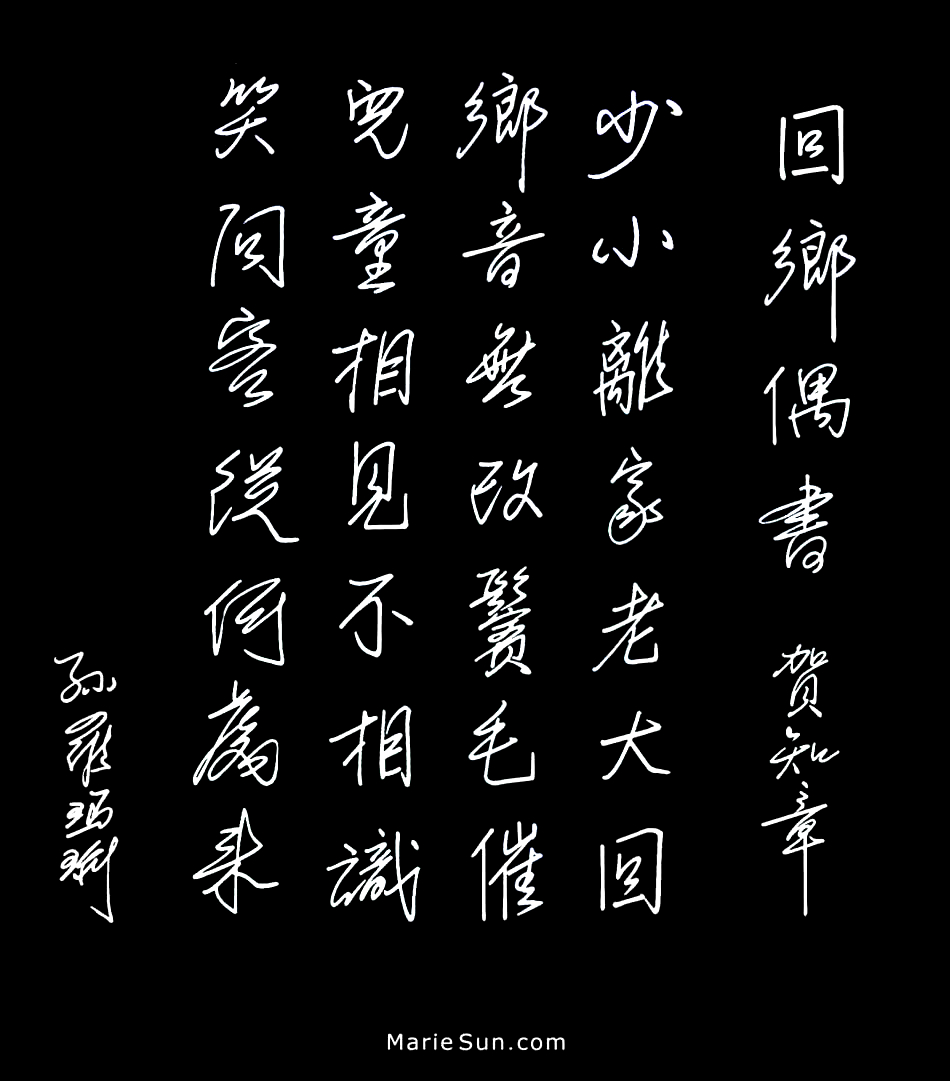

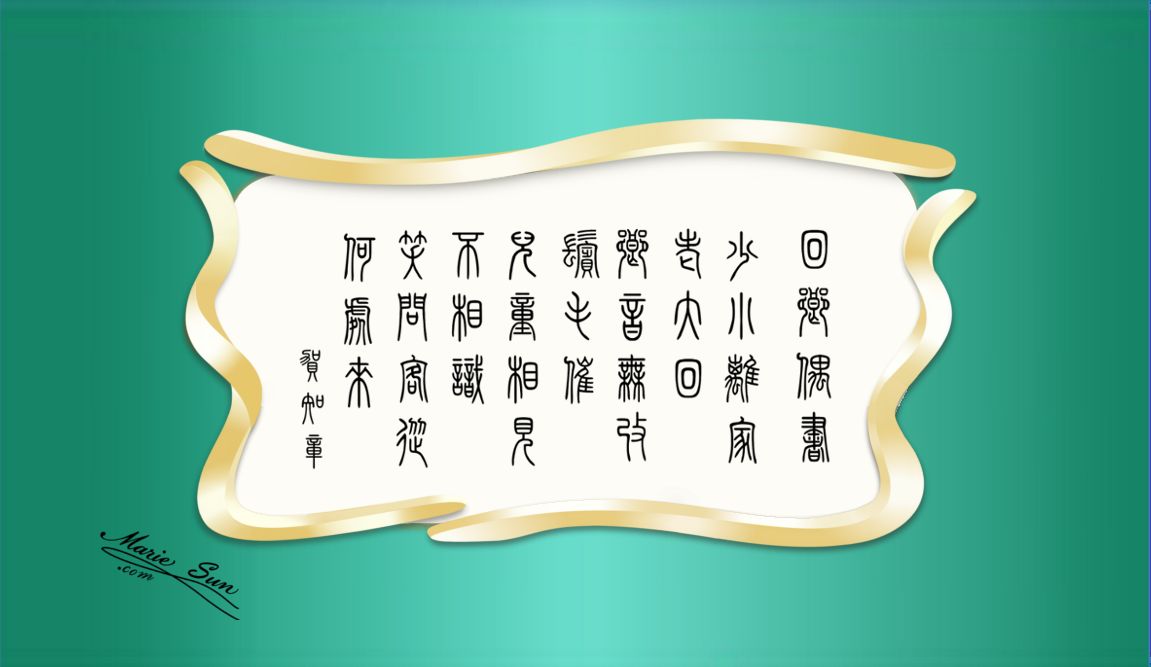

#01 Spring Dawn 春曉

Traditional Chinese

春曉 孟浩然

春眠不覺曉,處處聞啼鳥。

夜來風雨聲,花落知多少。

Simplified Chinese with *pinyin

春 晓 孟 浩 然

chūn xiǎo mèng hào rán

春 眠 不 觉 晓, 处 处 闻 啼 鸟。

chūn mián bù jué xiǎo, chù chù wén tí niǎo.

夜 来 风 雨 声, 花 落 知 多 少。

yè lái fēng yǔ shēng, huā luò zhī duō shǎo.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

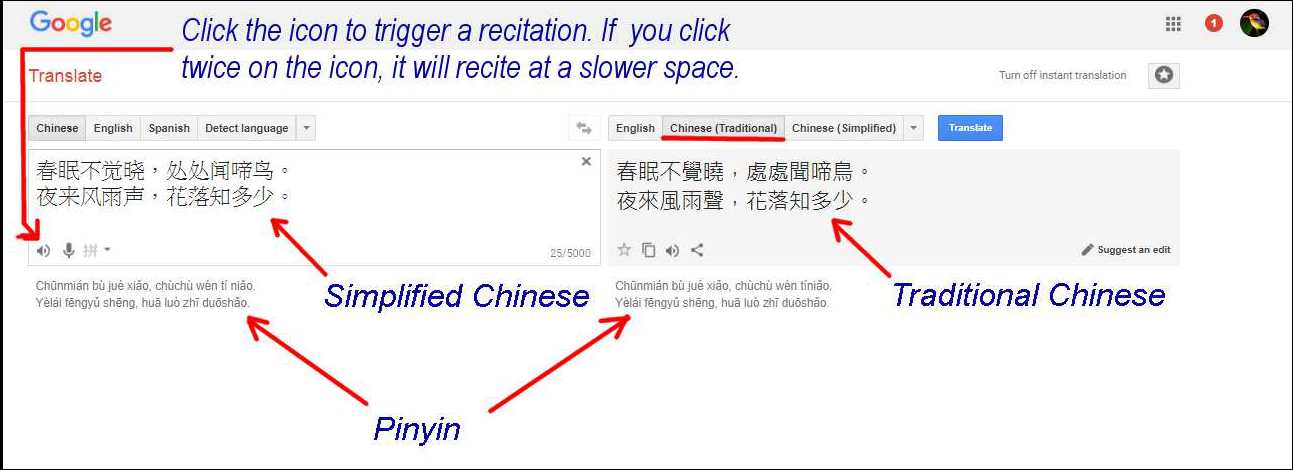

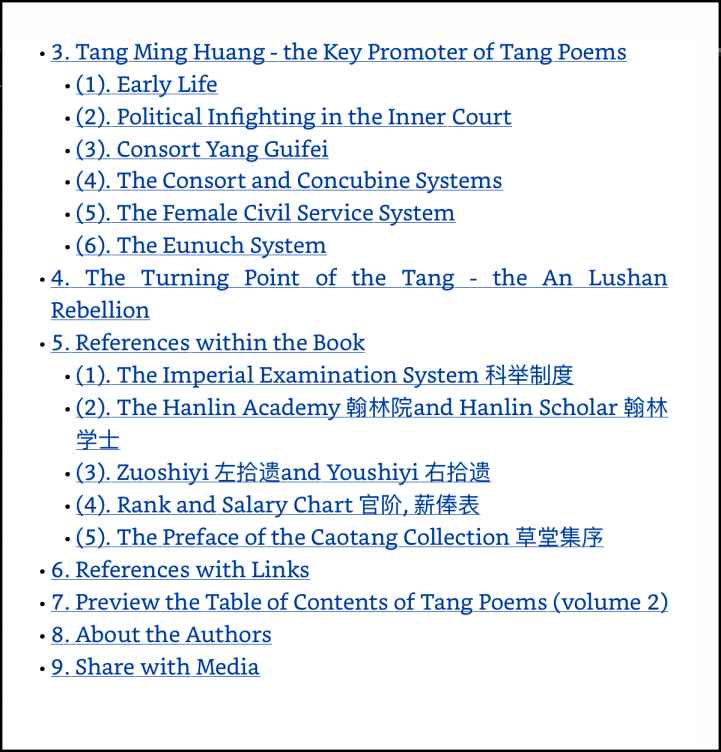

Recitation 1: How to listen to a recitation of the poem in Mandarin Chinese

and to view a transliteration into pinyin through Google. If click twice on the speak icon, it will

recite at a slower pace.

Recitation 2: Click and select one of the options to listen to a recitation.

* Pinyin 拼音:

Each Chinese Character has only one syllable. There are about 50,000 Chinese characters

(a person need only master two to three thousand, however, to be able to read newspapers) and several

tones are often used to differentiate words from each other. There are basically four tones in the Mandarin pinyin system.

For example:

| Pinyin |

Tone Symbols |

Tone Codes |

Tone Terms |

Chinese Characters |

English Meanings |

| ma |

none or

ˉ |

1 |

阴平 |

妈 |

mother |

| má |

ˊ |

2 |

阳平 |

麻 |

hemp or numb |

| mǎ |

ˇ |

3 |

上声 |

马, 玛, 蚂, 码 |

horse, agate, ant, code |

| mà |

ˋ |

4 |

去声 |

骂 |

scold |

Listen to the recitation of the above four tones - 妈, 麻, 马, 骂 (Mā, má, mǎ, mà) thru

Google US,

Google Hongkong or

Youtube.

The tones and cadence lead to the further enjoyment of the poems

as most of them are based on certain regulated

tone/cadence patterns and rhymes that enhance the ability of recitation and gracefulness. While reciting Tang poems in Mandarin is a delight,

it is even more so in the southern dialects of Chinese, such as Cantonese and Fujianese, which have preserved more than four tones, especially the tone of 入声 [Rù shēng] prevailed in dialects during the Tang period.

You may refer to the references at the end of the book for chanting poems in Cantonese or Mandarin with the tone of 入声 [Rù shēng].

* * *

Spring Dawn Meng Haoren

Indolent sleeping in spring,

I'm unaware morning's here.

Clearly I can hear,

Birds' twittering everywhere.

With last night's gust of wind and rain,

I'm wondering -

How many flowers

Have fallen and scattered.

* * *

Meng used plain and simple

words to describe a spring morning scene.

His poems are often filled with charming descriptions of nature.

Most of his landscape poems reflect beings and objects coexisting in natural harmony.

This was a reflection of his own life and pursuits - to live in the world without harming it or attempting to "conquer" it. But, rather, to preserve it as it was, and to be part of it and enjoy it.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

If there are several meanings for a character or a term, the ones complying best to the poem's generally understood intent are listed first.

春晓: spring dawn 春: spring 眠: to sleep, to hibernate 不觉: unaware, hard to sense, unconsciously 晓: dawn, daybreak, to know, to tell

处处: everywhere, in all respects 闻: to hear, to smell, to sniff at 啼: to twitter, to sing, to cry, to weep aloud, to crow, to hoot

鸟: bird 啼鸟: bird's chirping, bird's twittering, bird's singing

夜: night 来: come, return 风雨: wind and rain 声: sound, voice, tone, noise

花: flower, blossom 落: fall, drop 知: to understand, to know, to be aware 多少: how many, how much, which (number), number, amount, somewhat

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Xiangyang, Hubei Province 襄阳, 湖北省 - Meng Haoran's hometown:

View thru Google or

Baidu.

2. Chinese calligraphy 春眠不觉晓书法:

view thru Google,

Baidu or

Yahoo Japan.

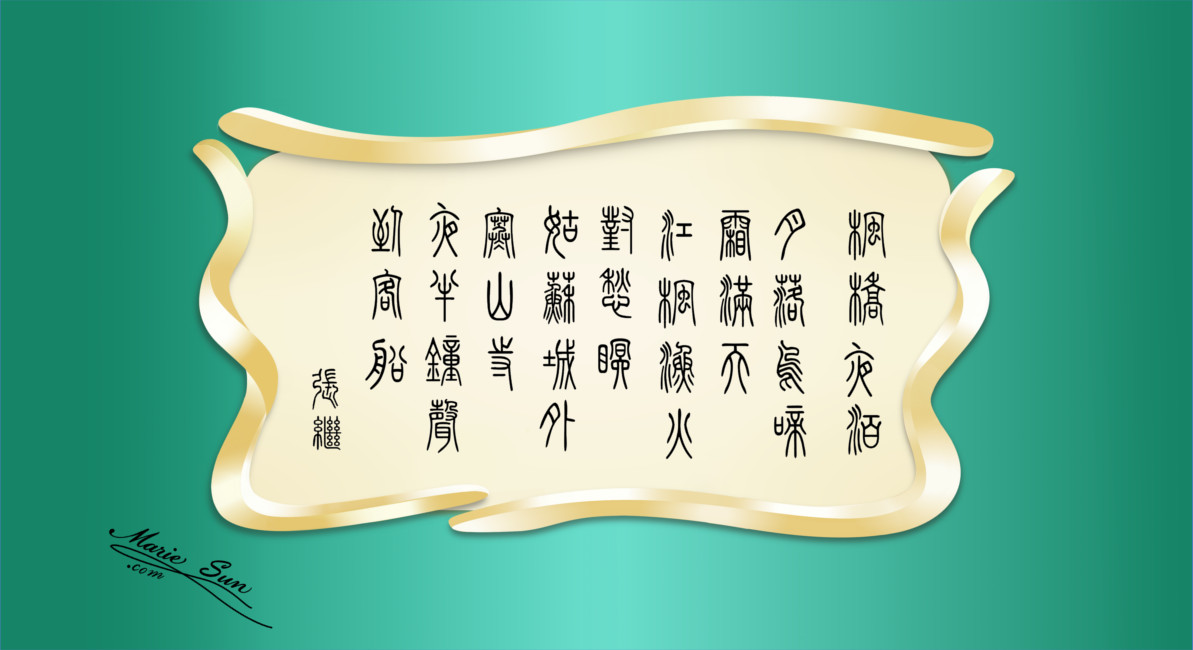

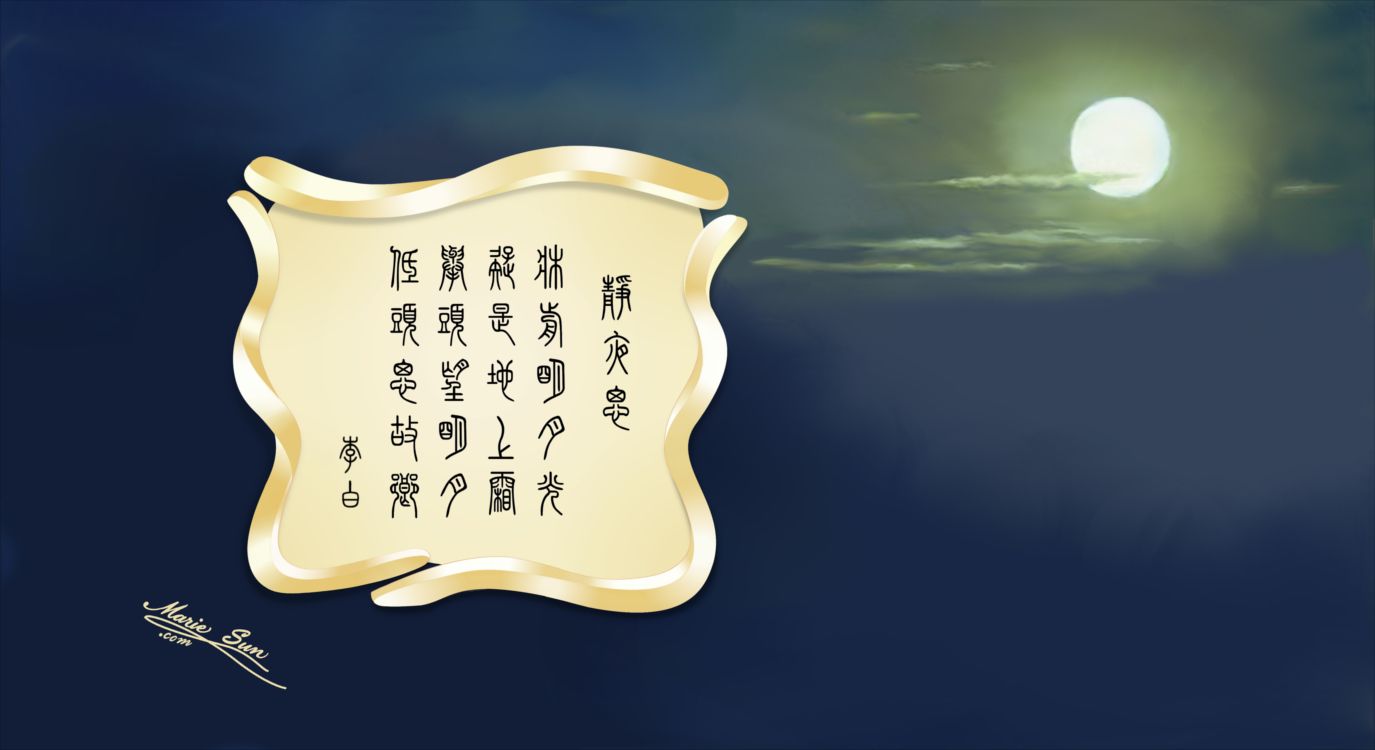

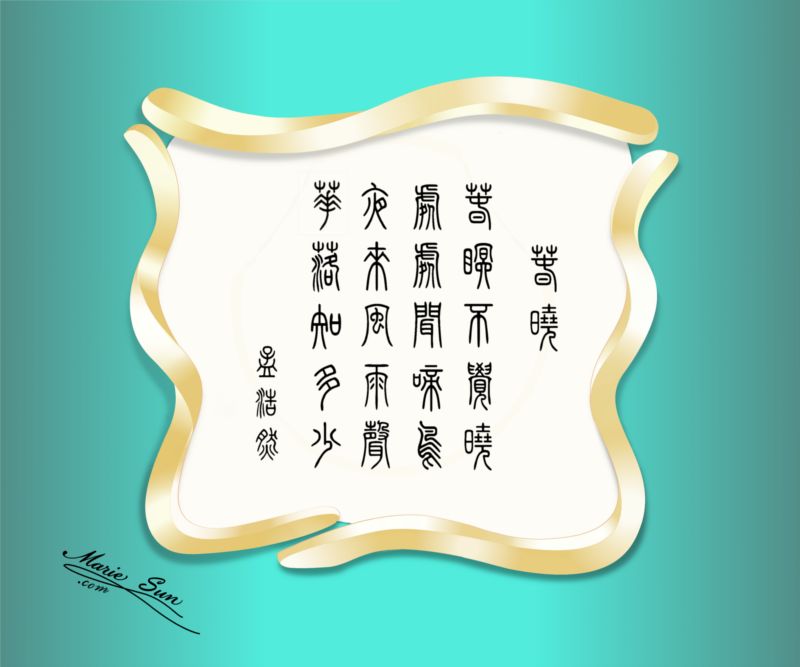

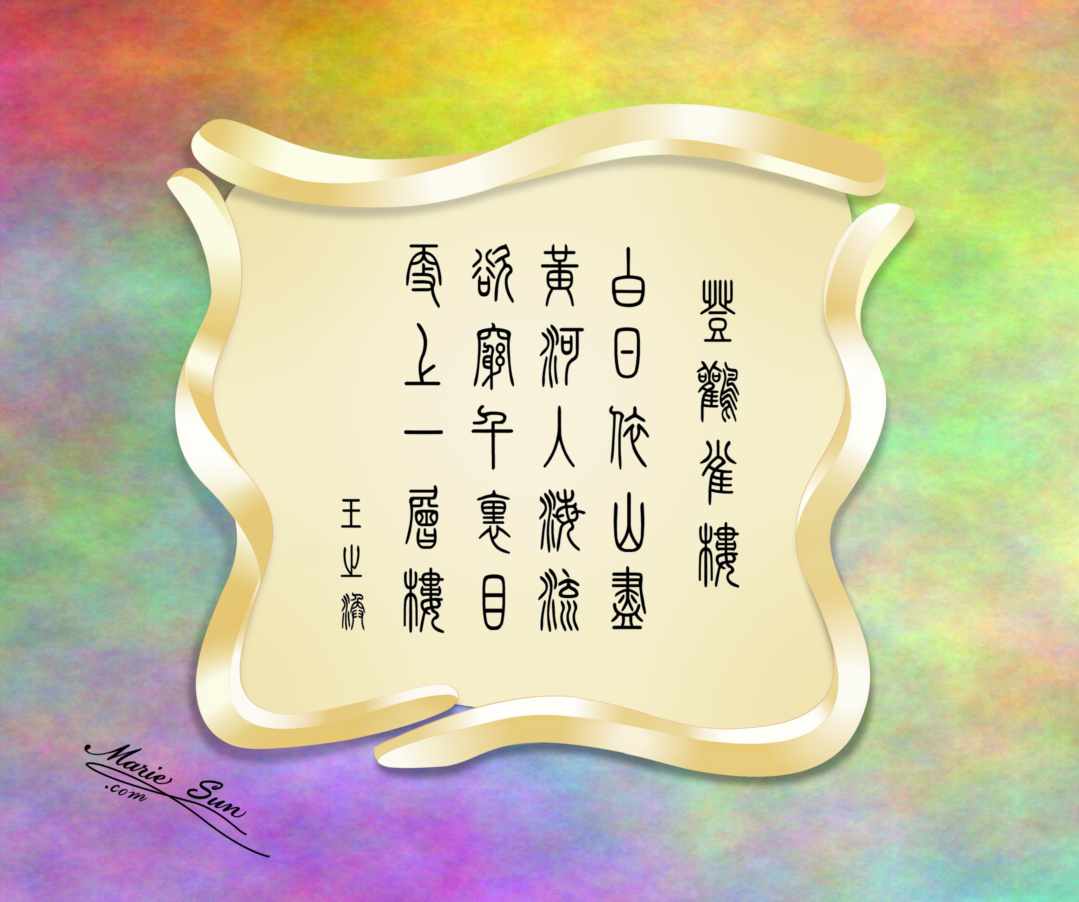

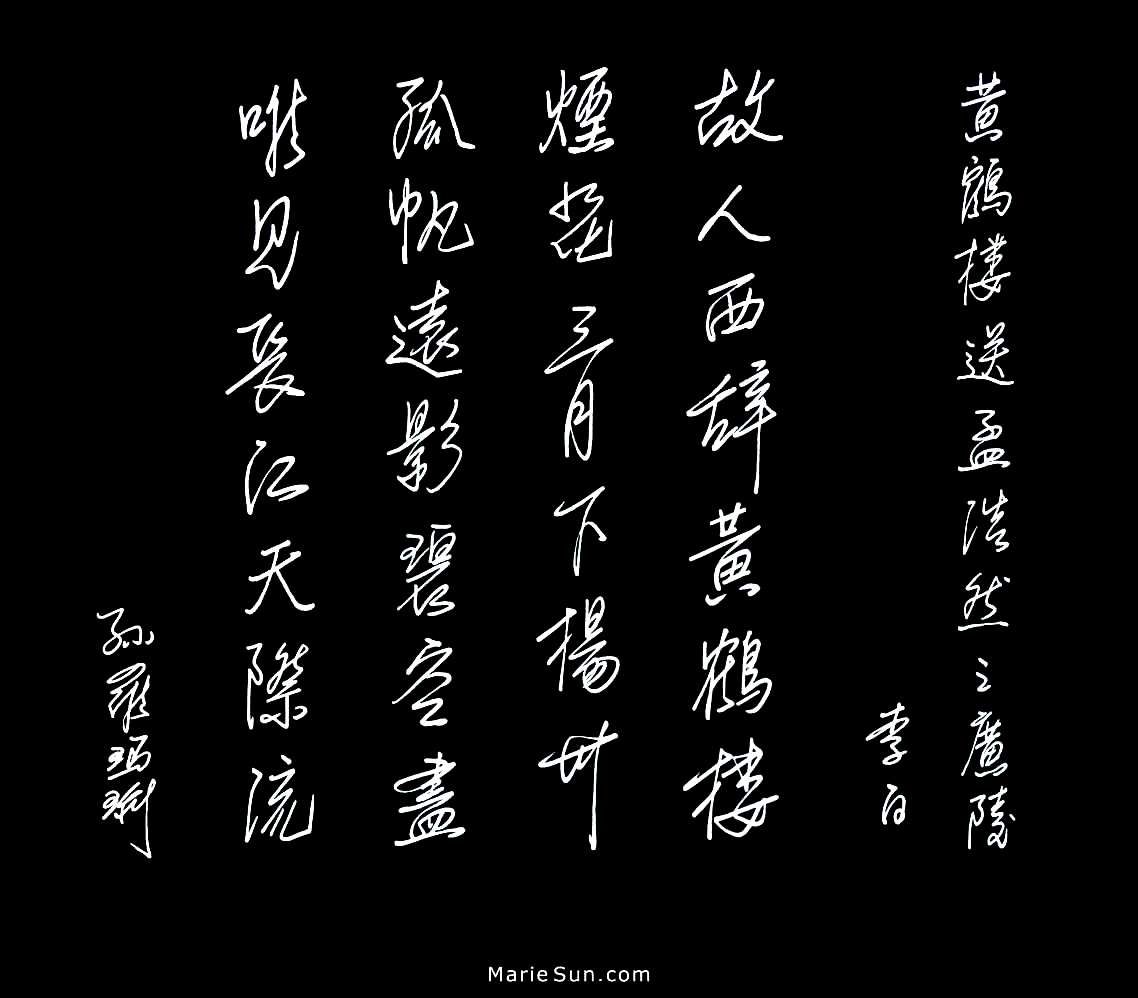

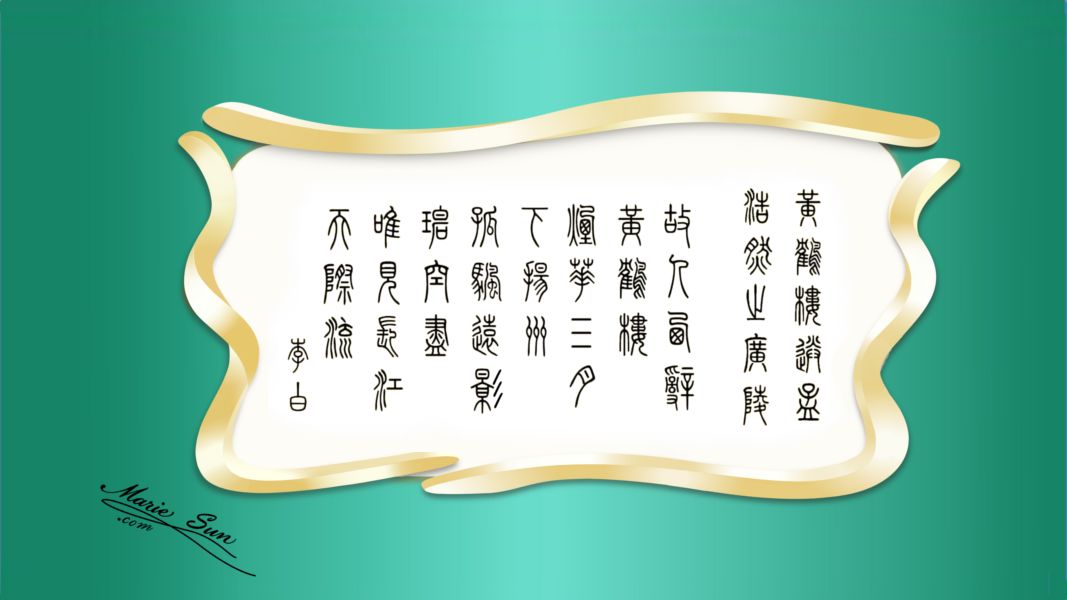

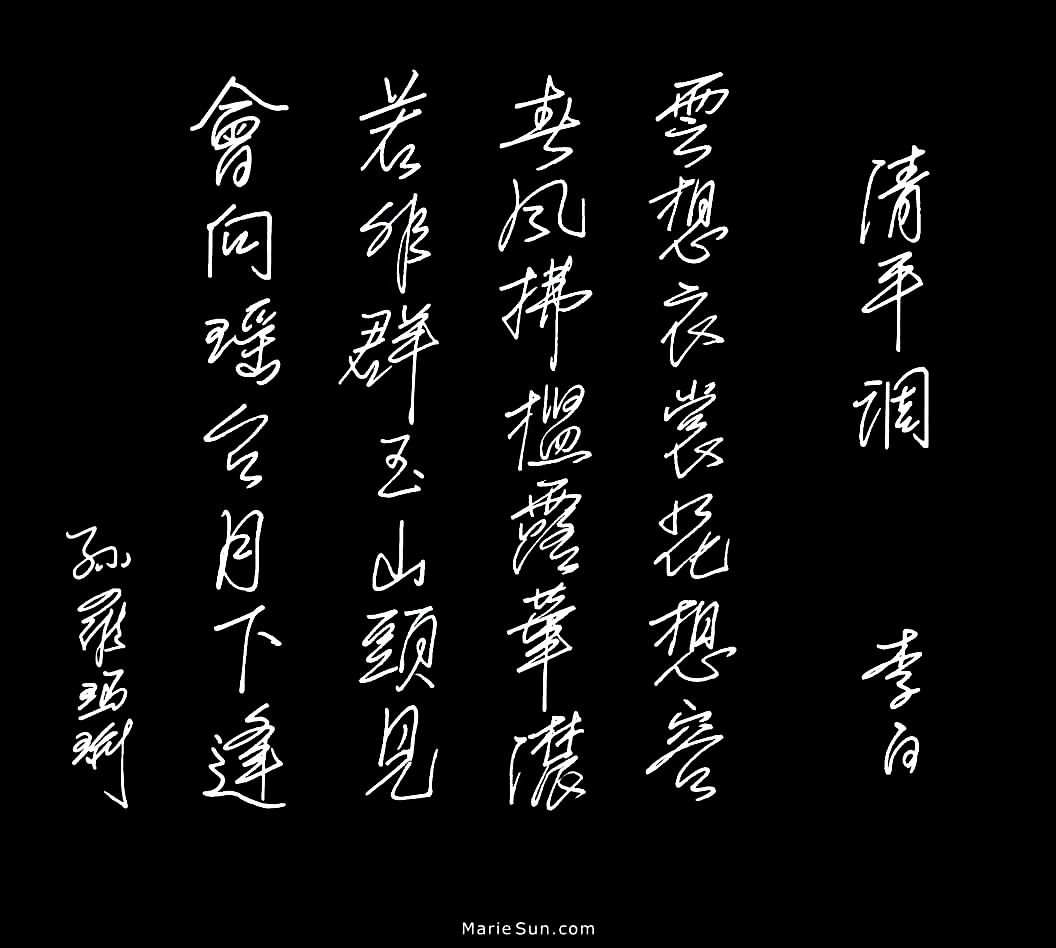

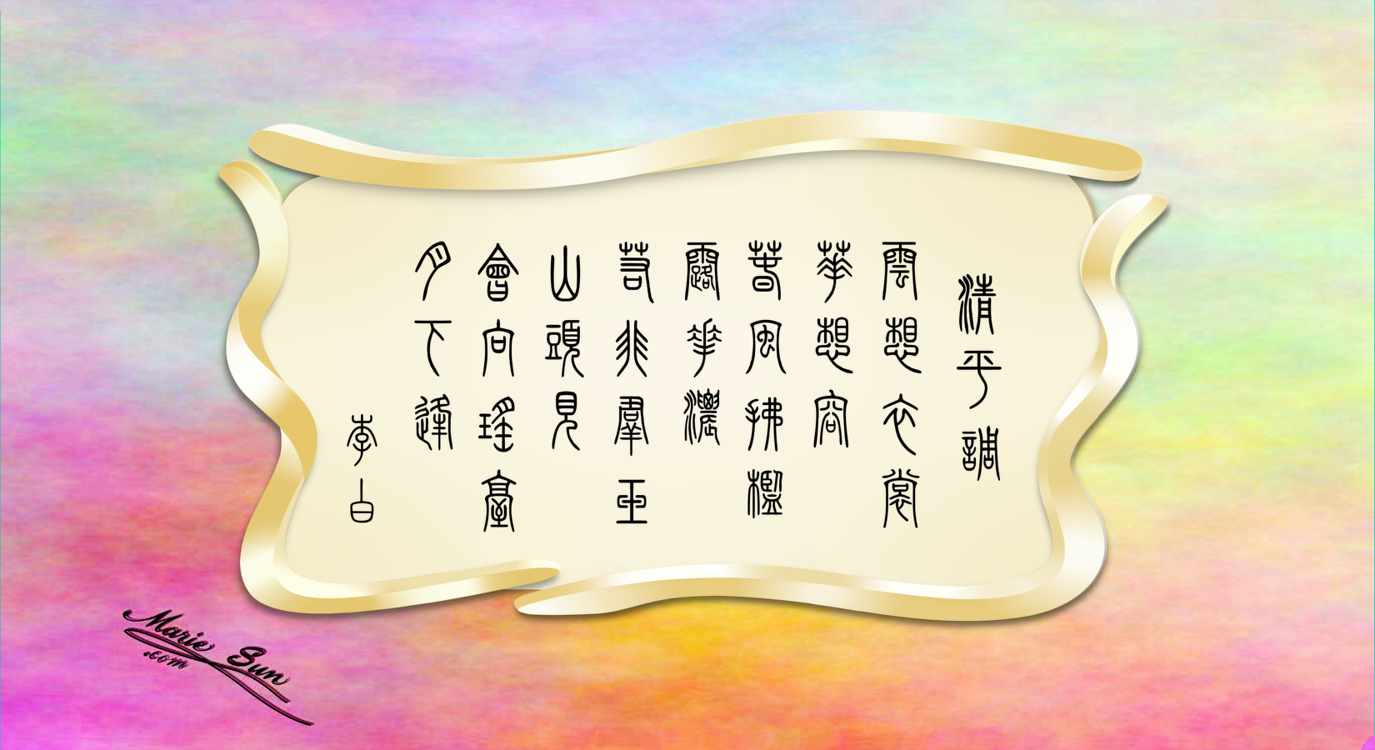

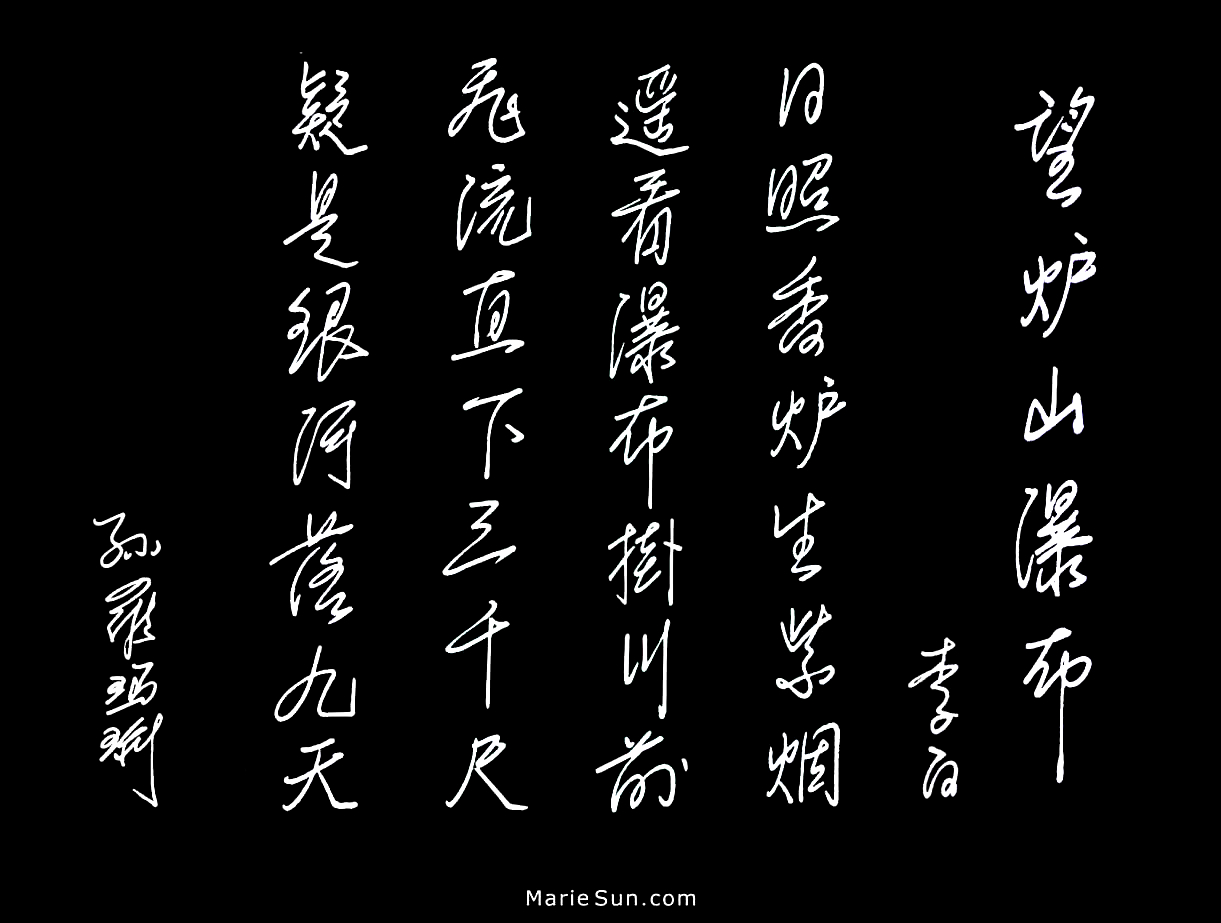

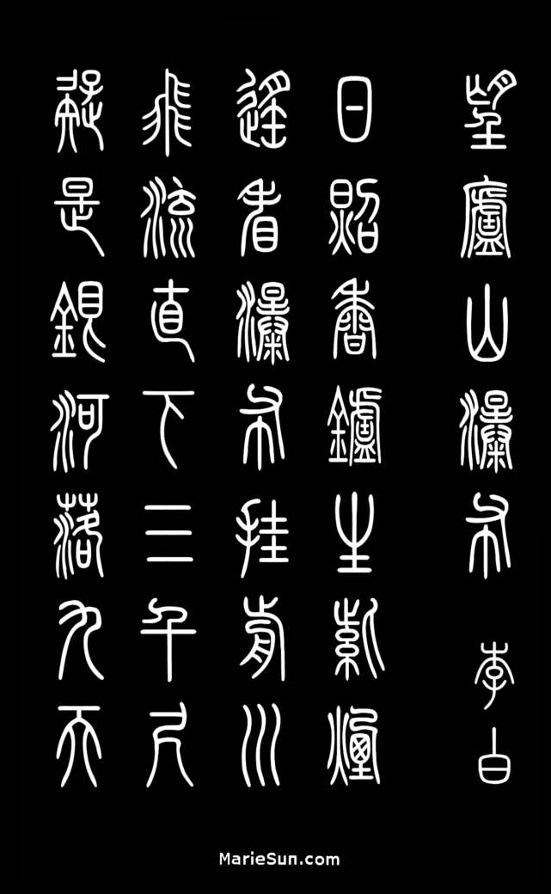

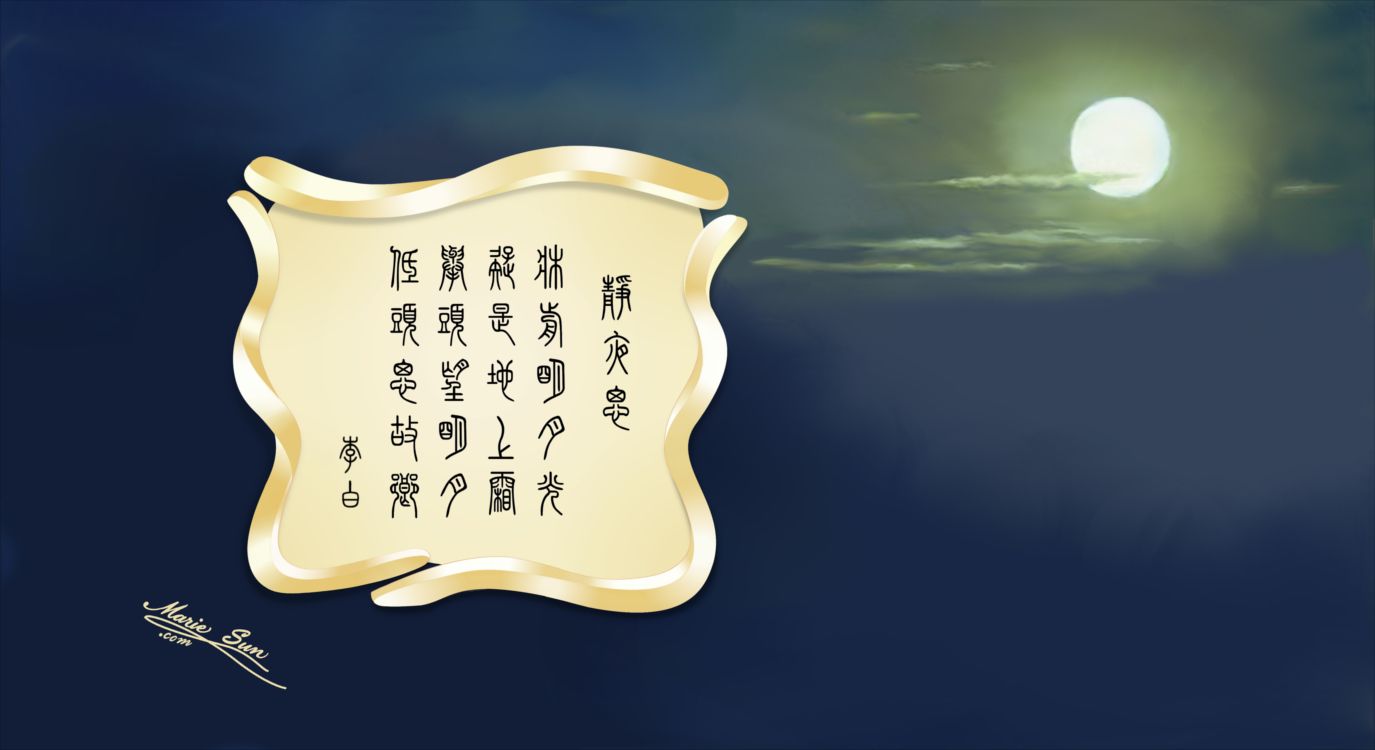

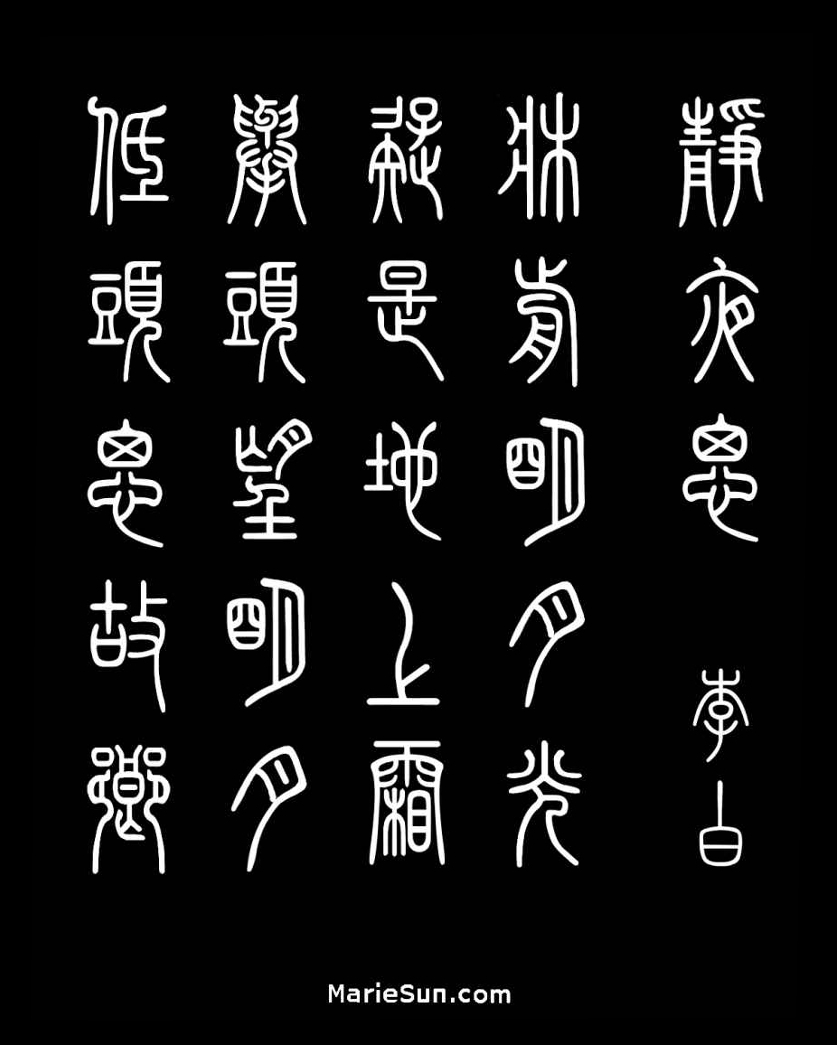

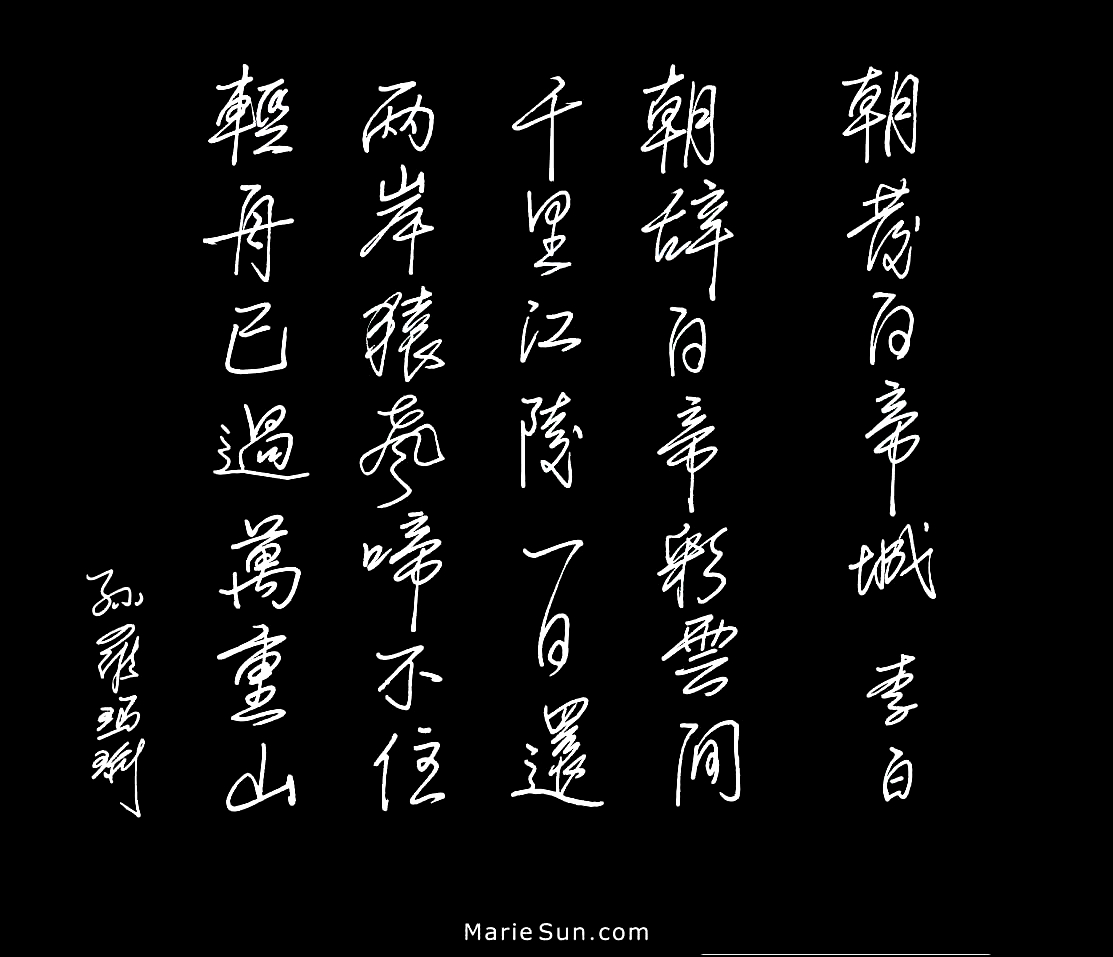

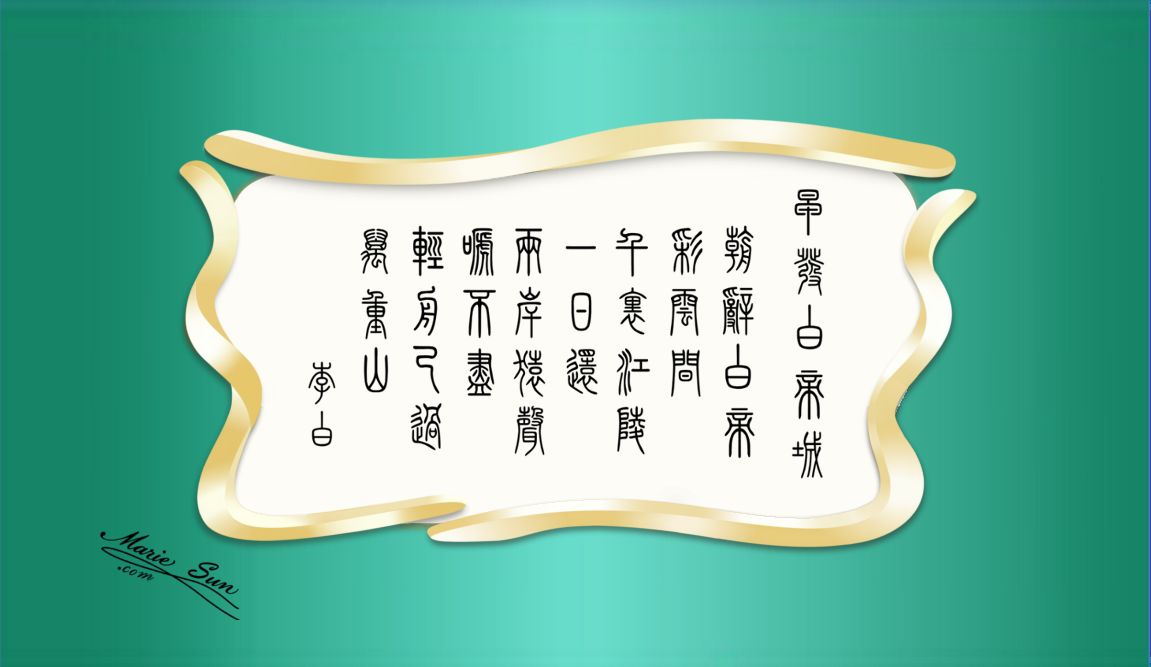

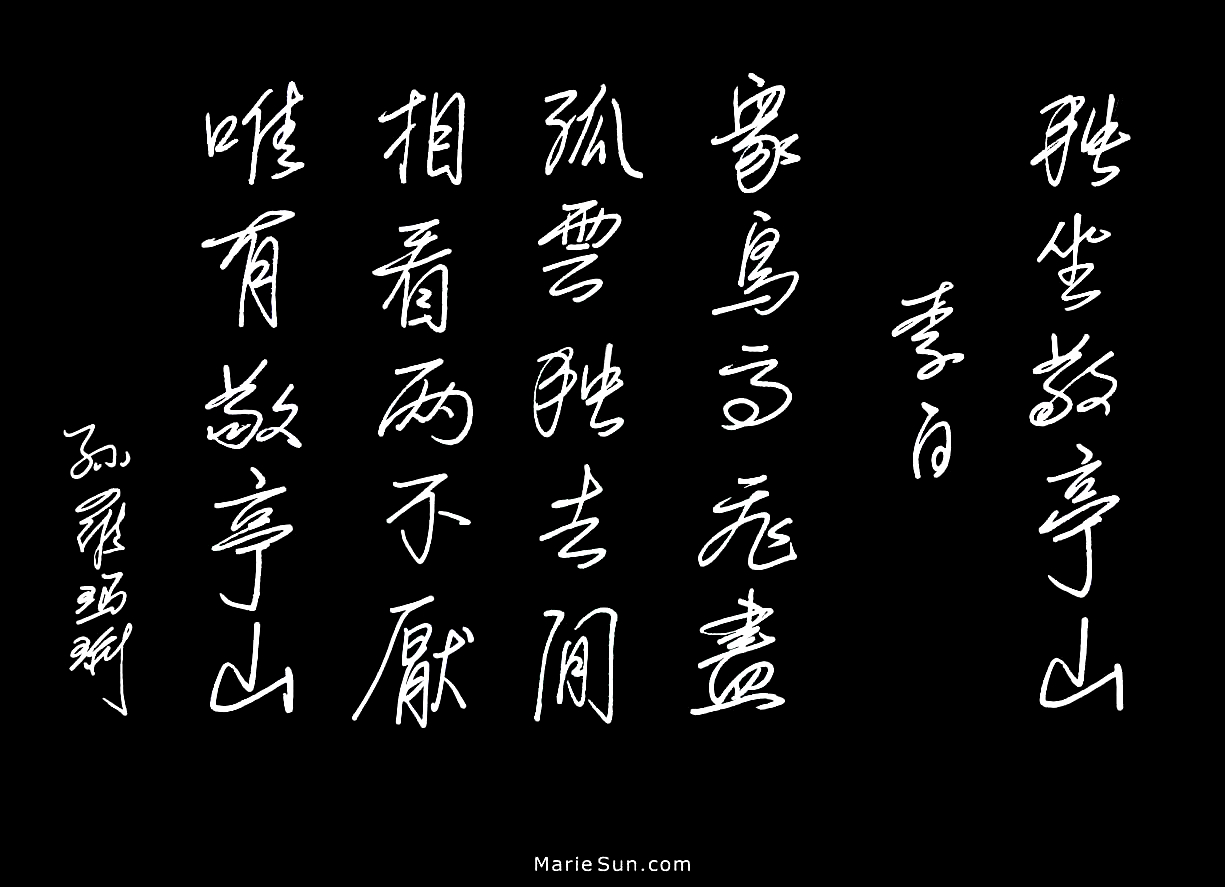

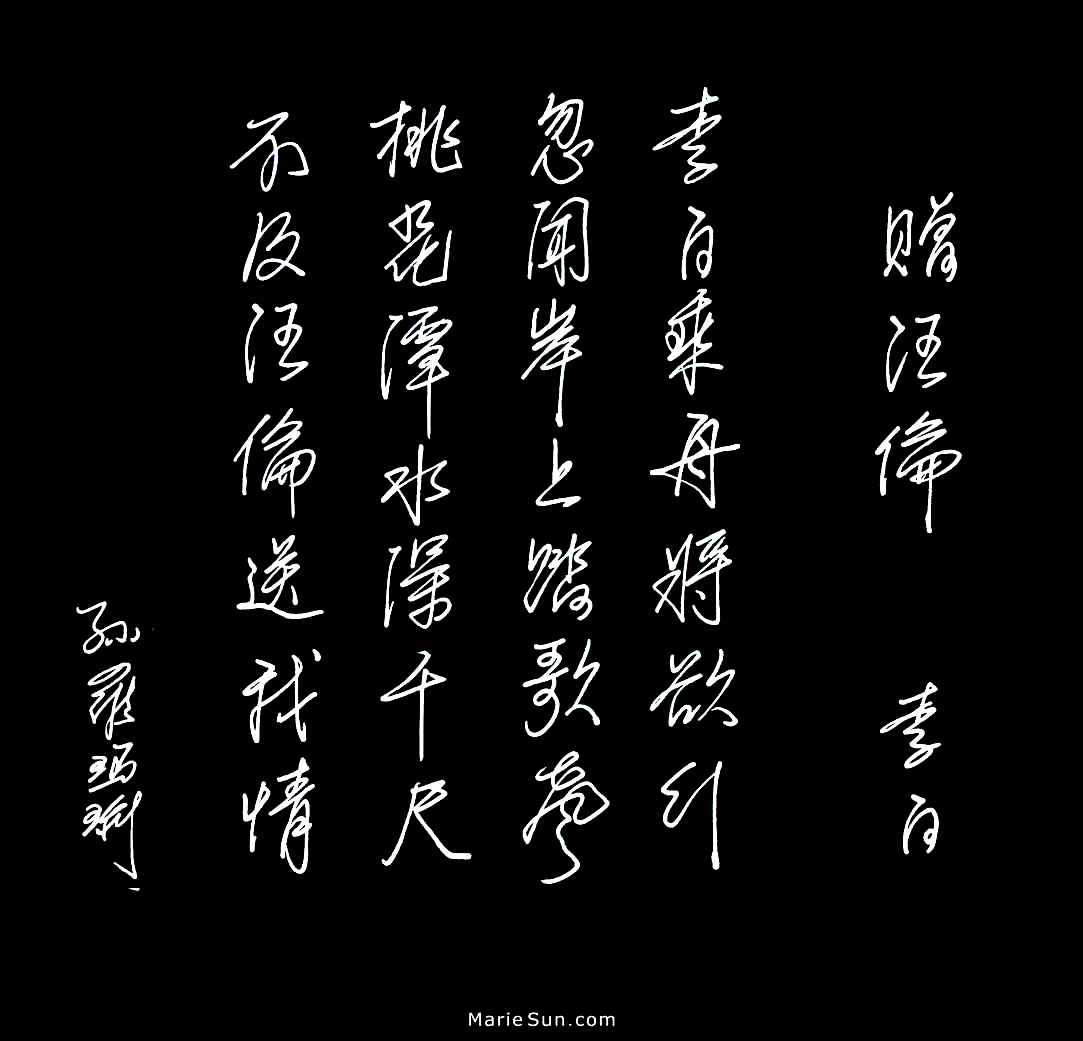

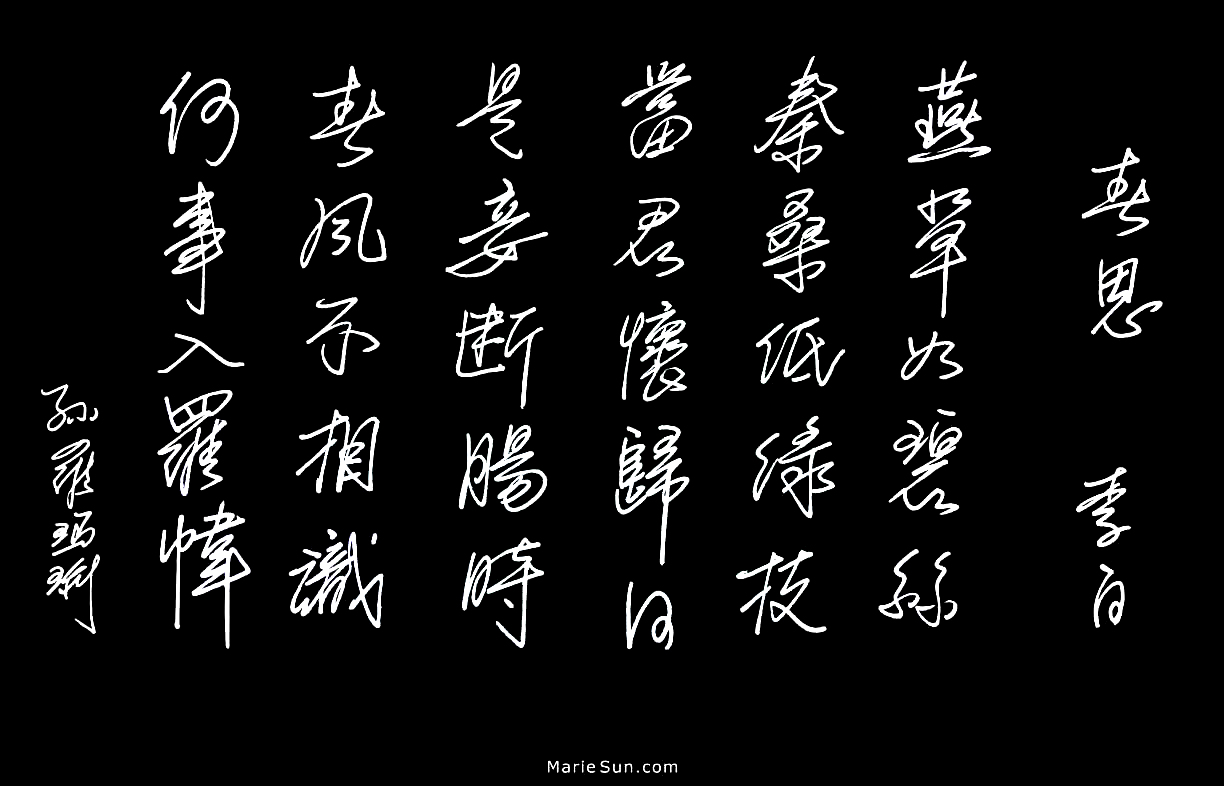

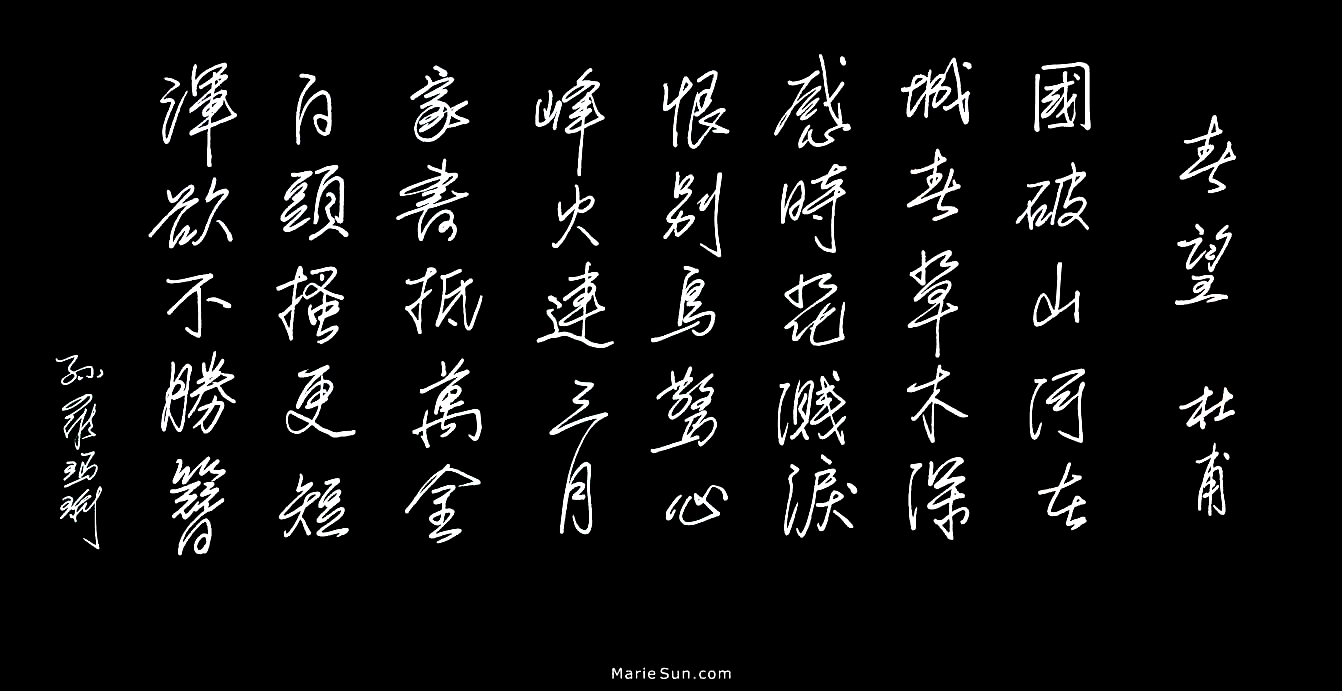

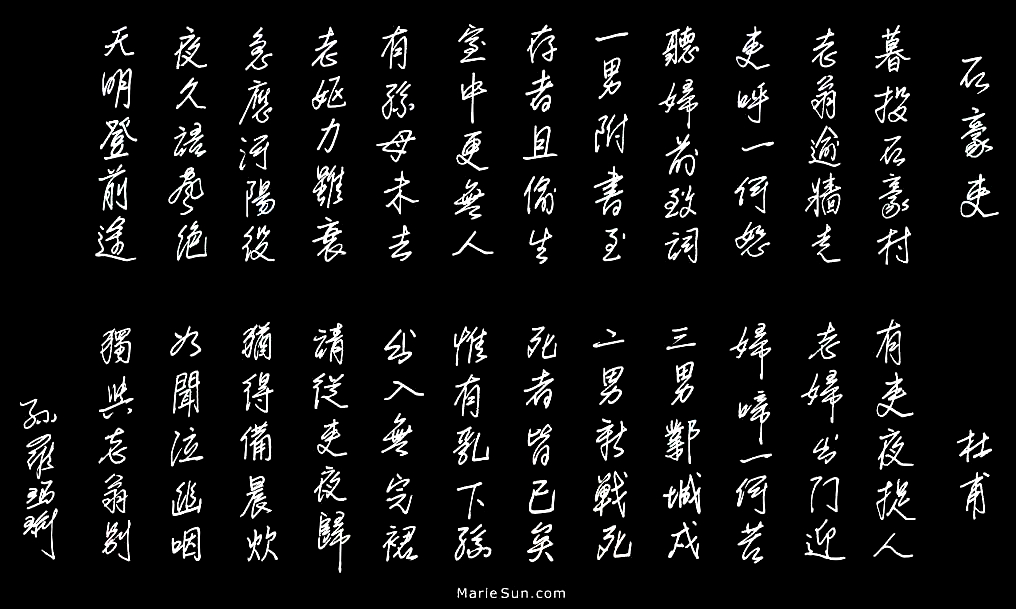

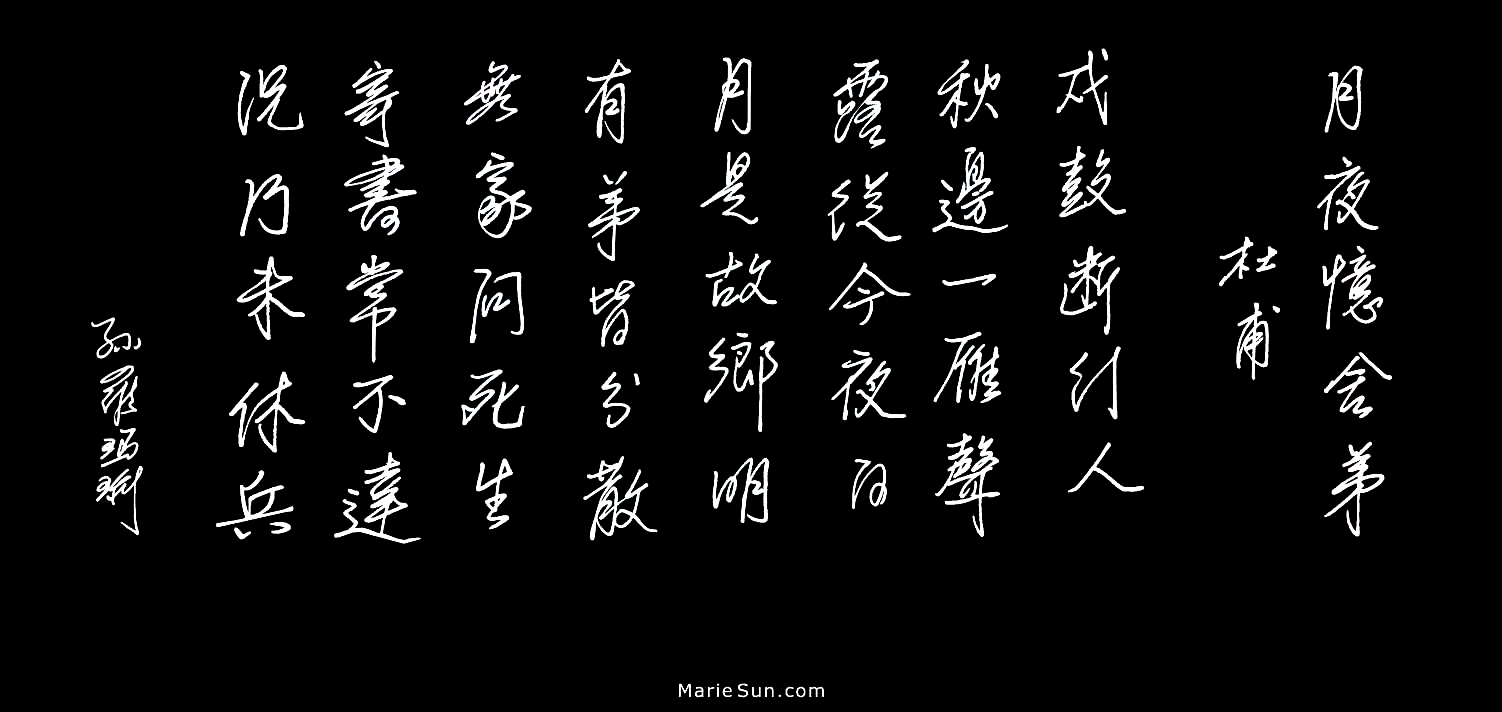

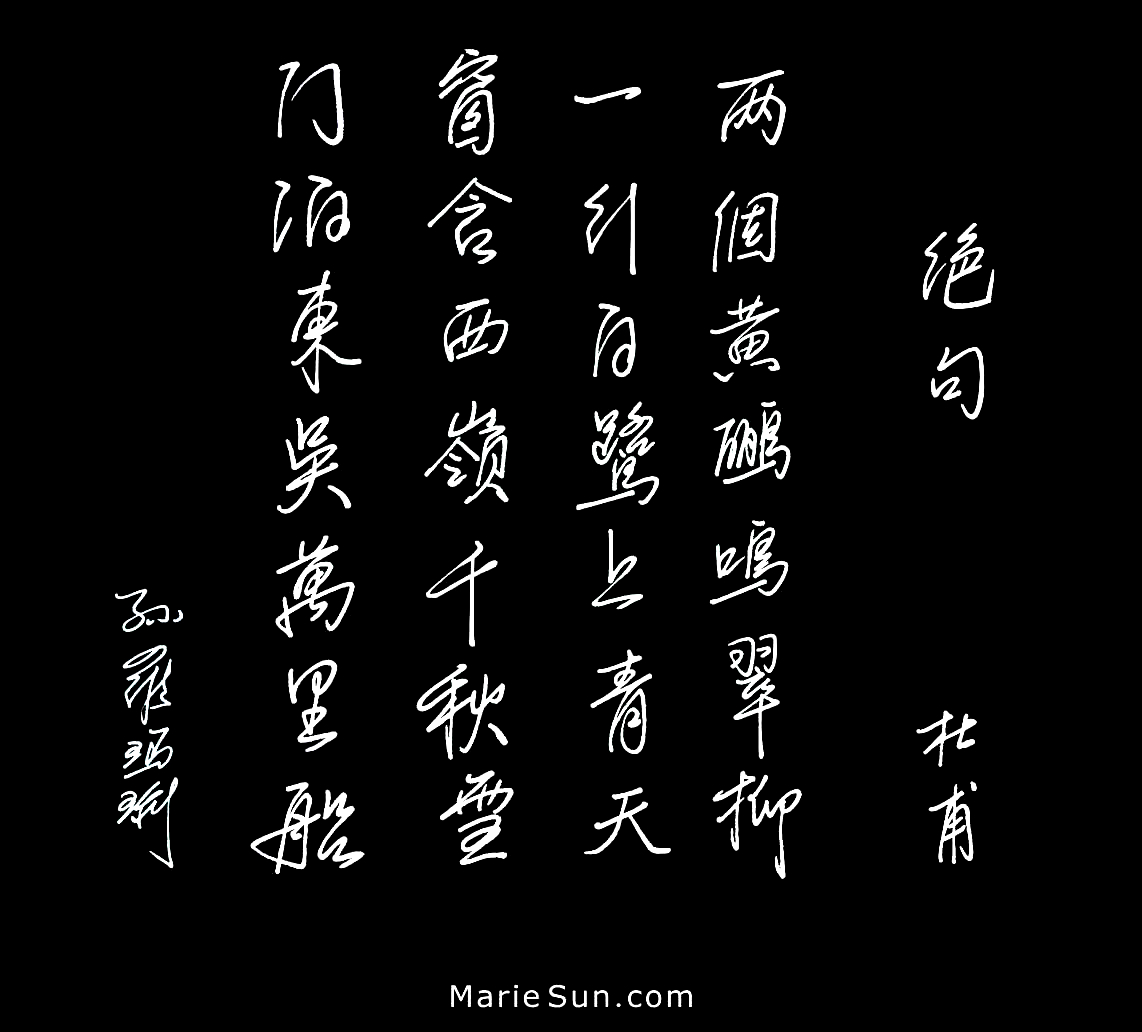

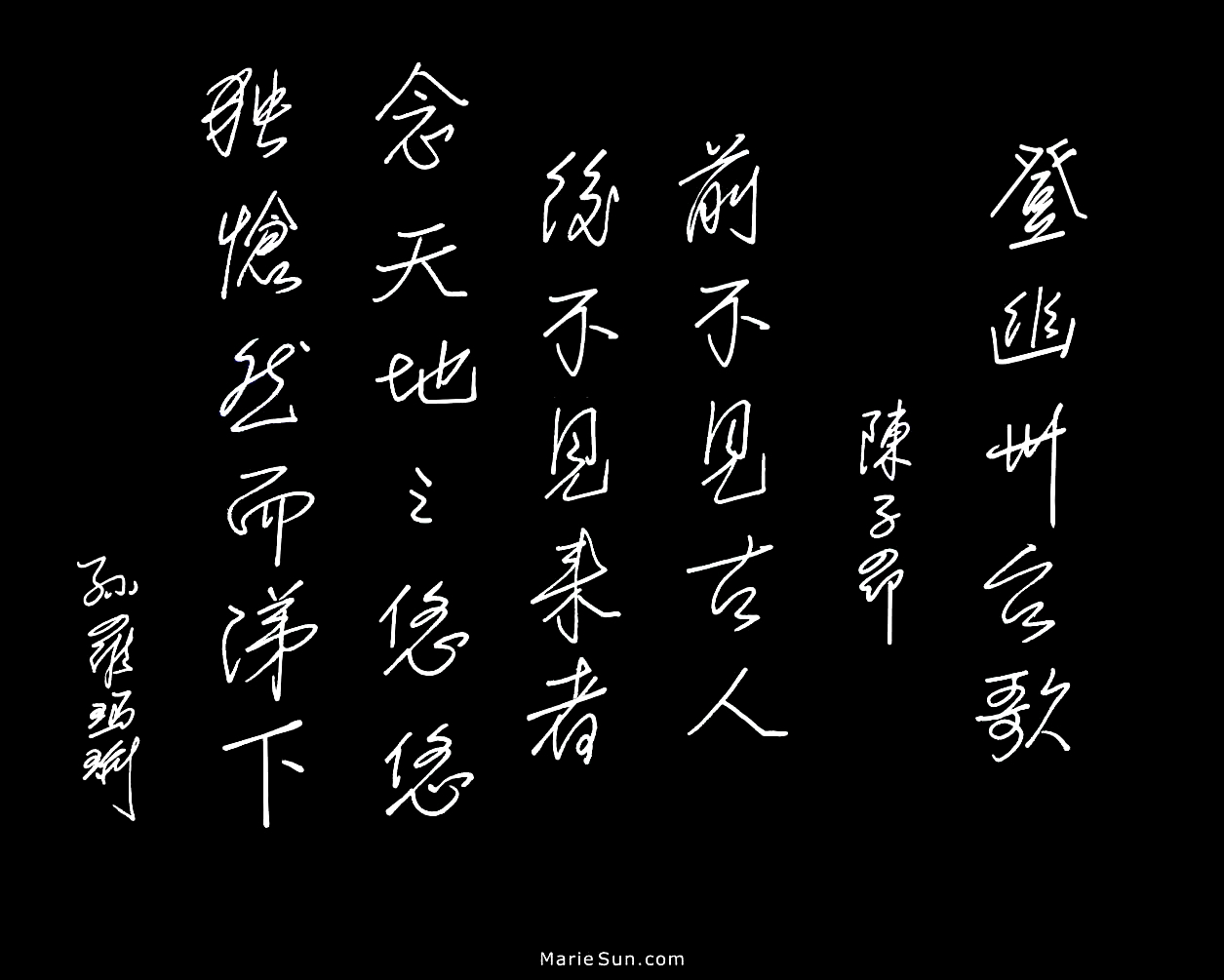

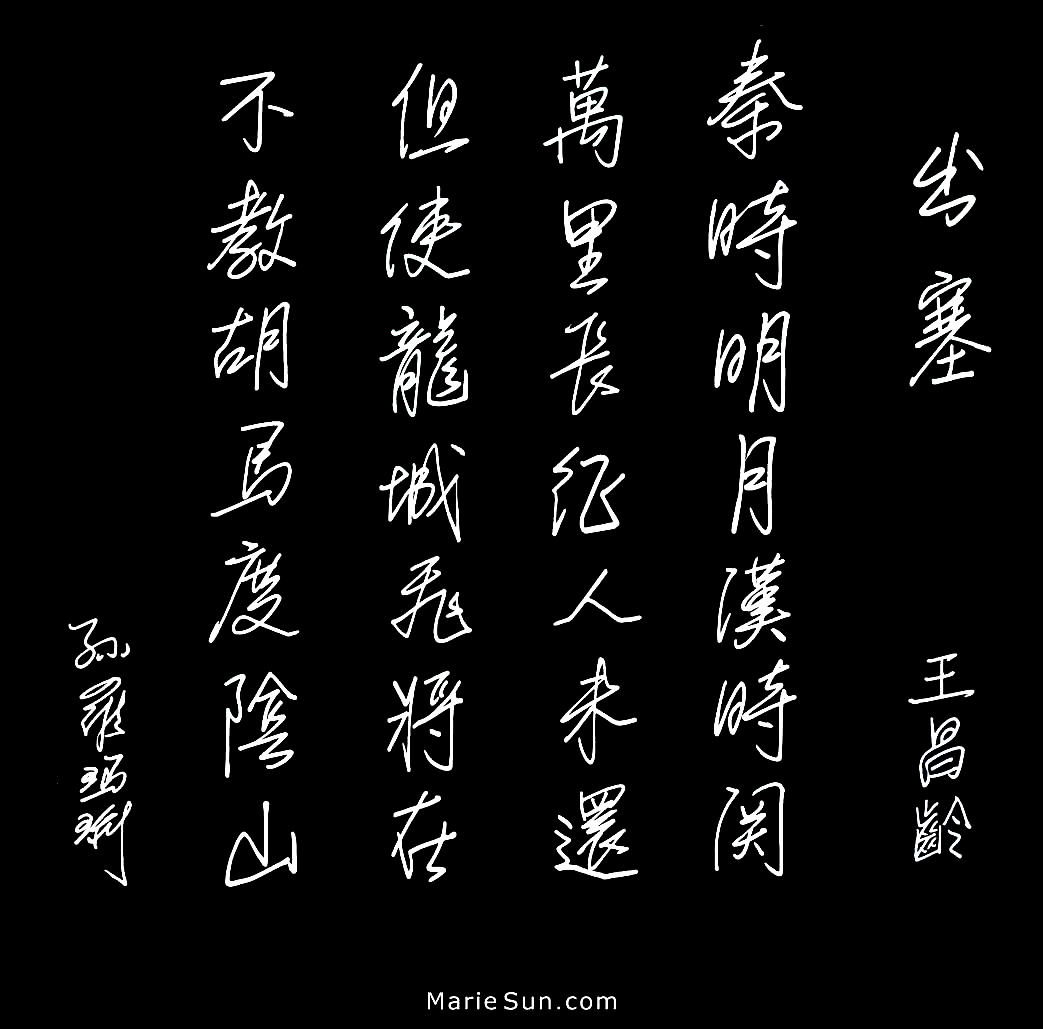

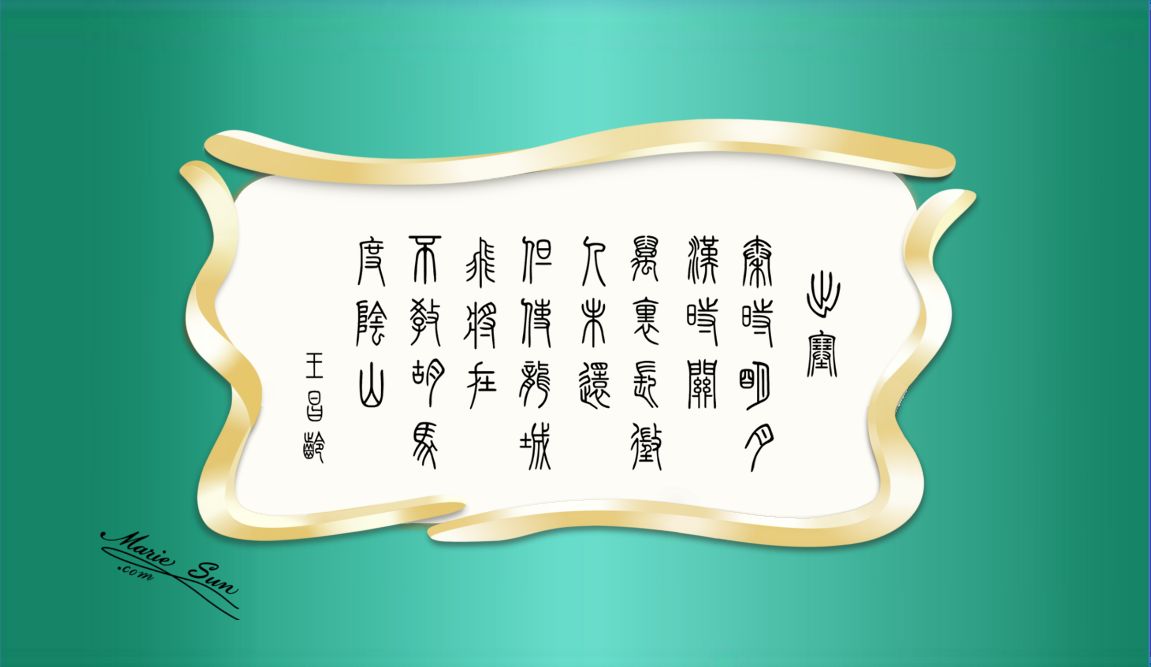

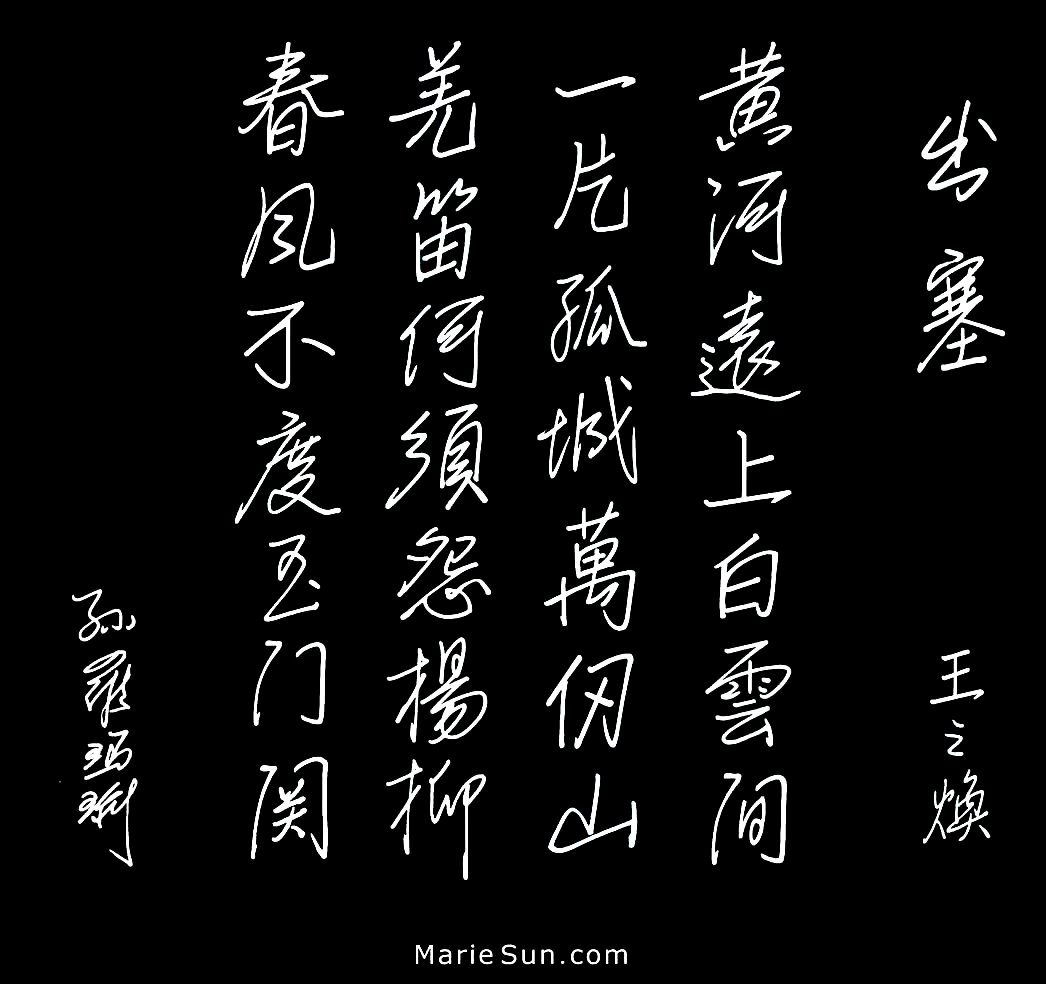

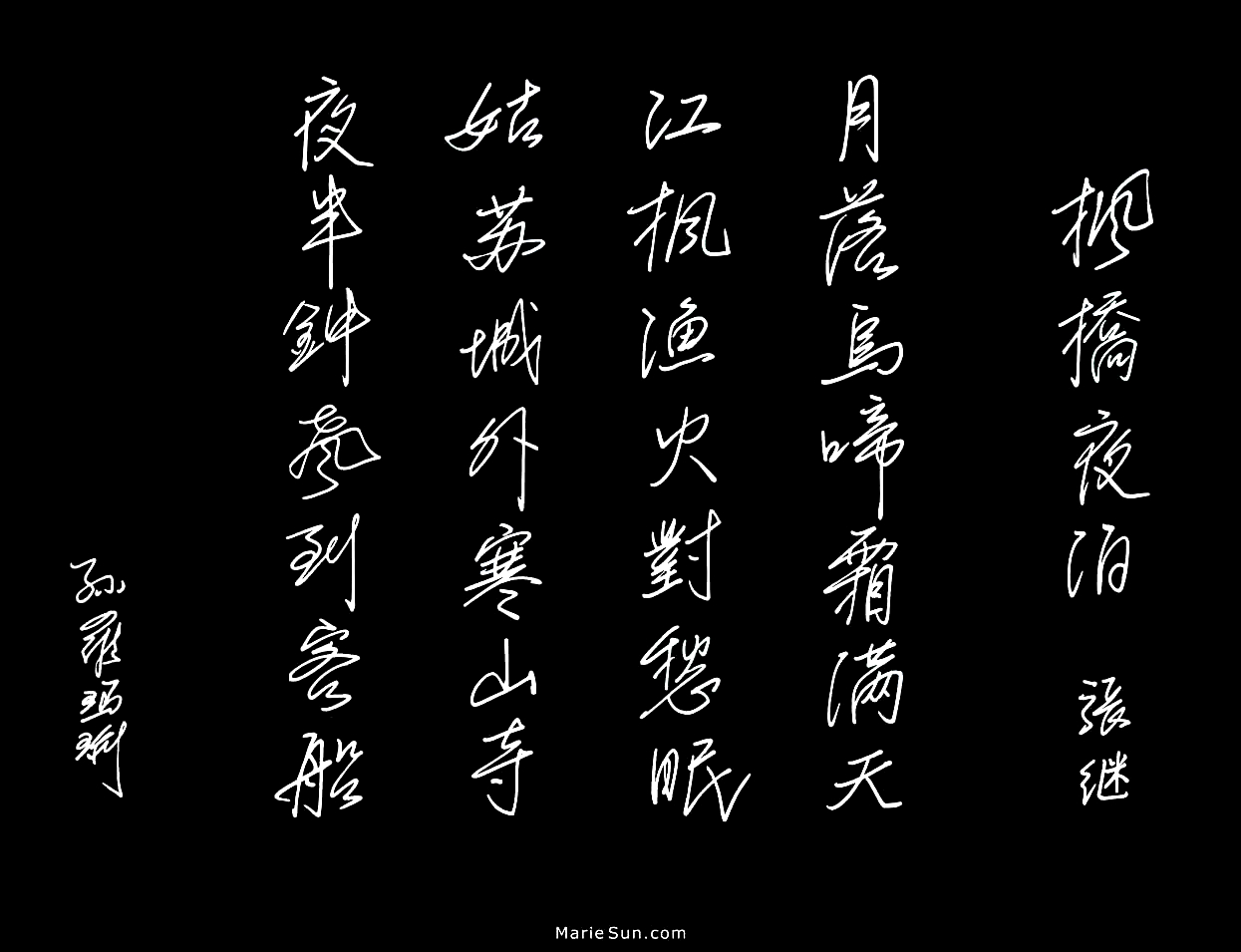

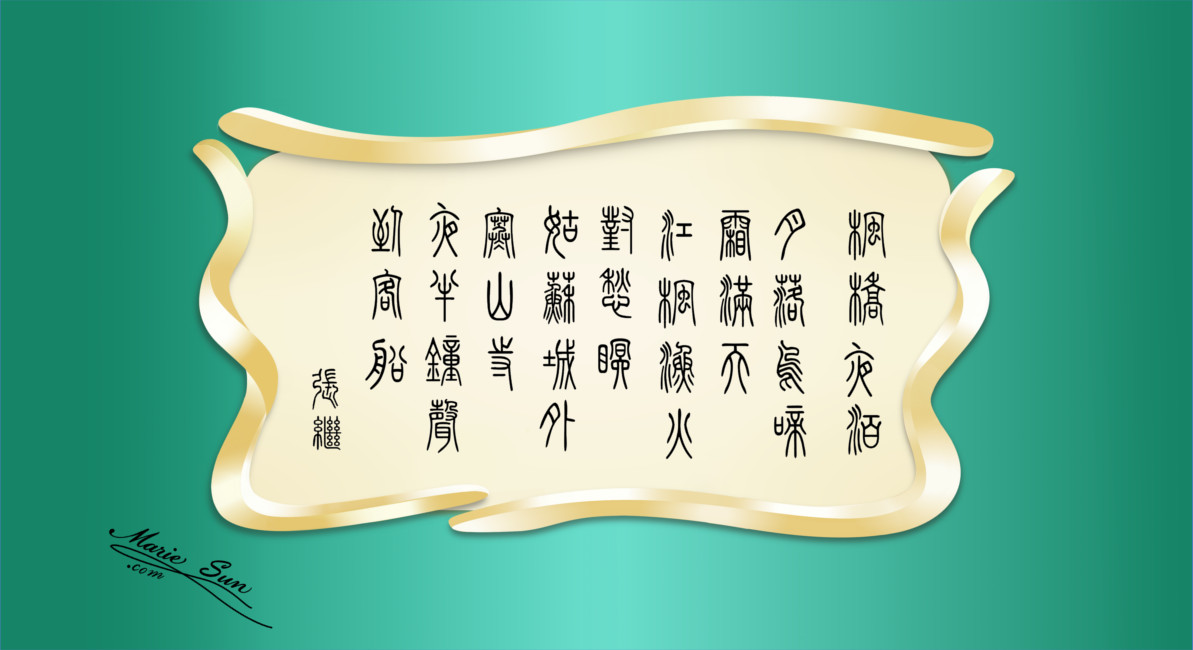

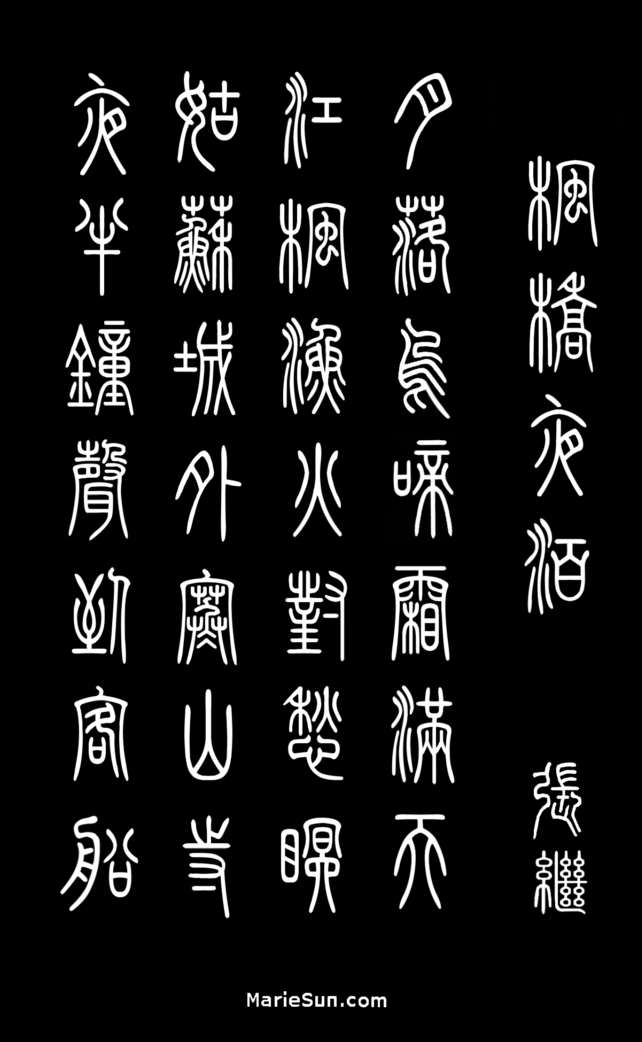

Throughout this book, the poems presented here as images follow the traditional Chinese manner - written in vertical columns from top to bottom and from right to left without punctuation:

|

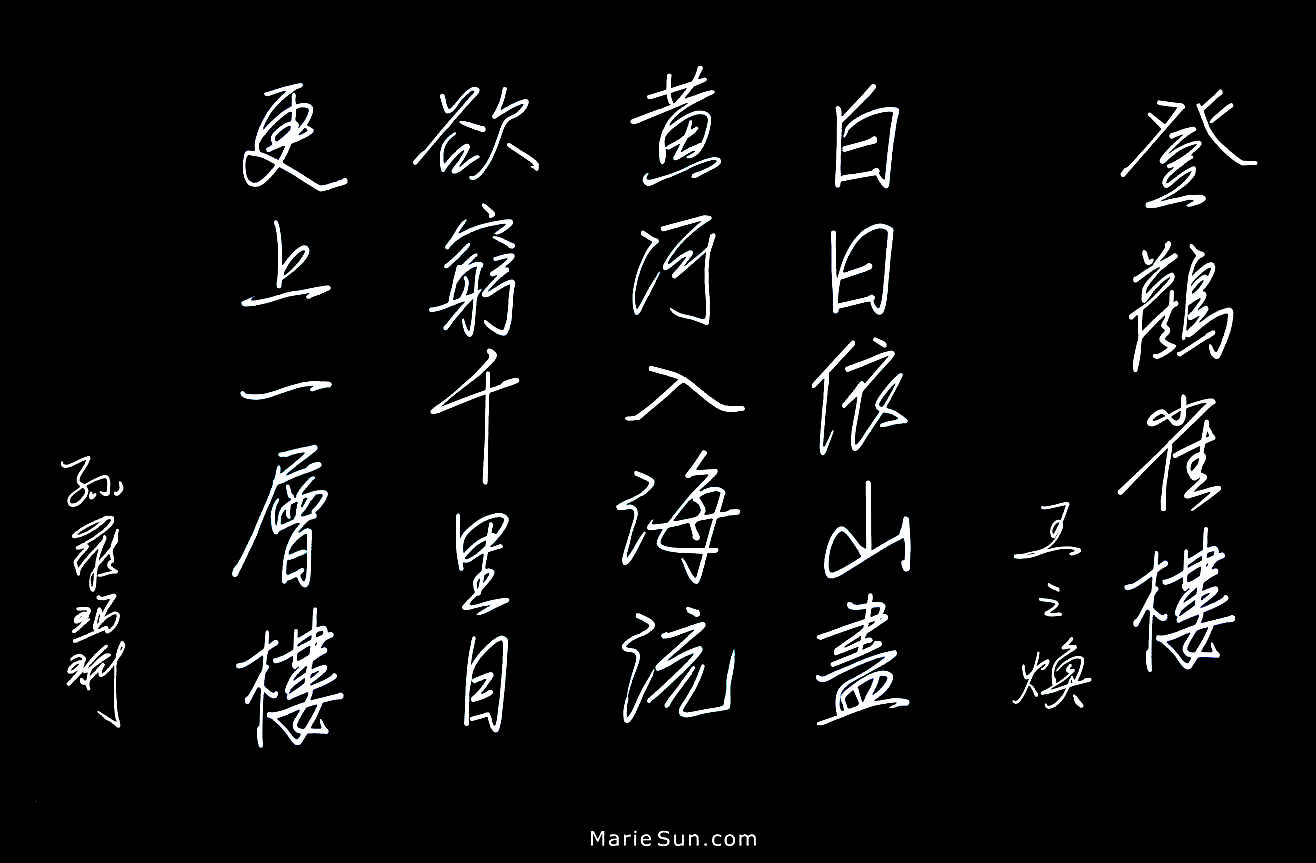

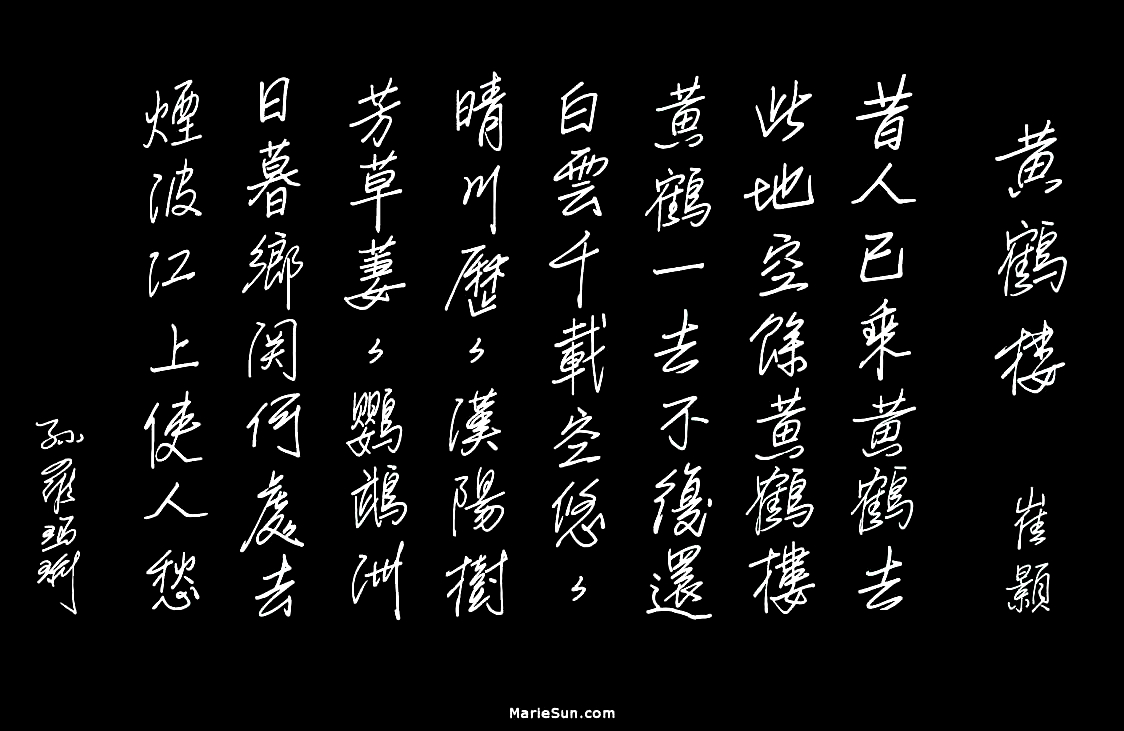

Calligraphy in xingshu 行书 style

|

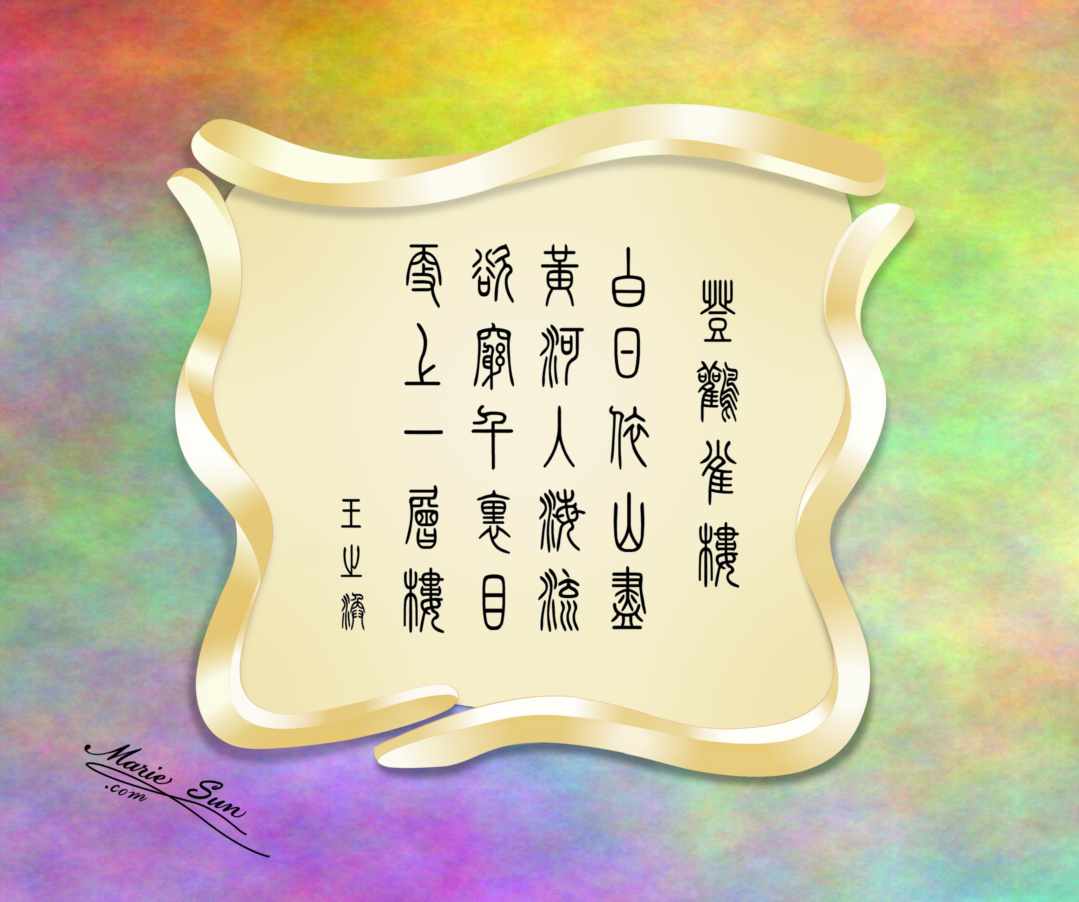

calligraphy in zhuanshu/zhuanzi 篆书/篆字 style

|

|

calligraphy in zhuanshu/zhuanzi 篆书/篆字 style

|

Li Bai 李白

Li Bai (701 - 762) lived mostly in the High Tang period and only a few years into the beginning of Mid Tang period; therefore, his writings often reflected the grandeur of the Tang Dynasty at the peak of its prosperity.

He was the most famous romantic poet in Chinese history, penned numerous masterpieces that are still memorized and chanted by Chinese of all ages today.

Due to his seminal role in Tang poetry, extra attention and detail has been given to his background, and a special section has been set aside at the end of all of his poems to address his history. As for the biographies of the other poets in this book, however, completely precede their poems.

* * *

#02 Seeing Meng Haoran off at Yellow Crane Tower 黄鹤楼送孟浩然之广陵

Traditional Chinese

黃鶴樓送孟浩然之廣陵 李 白

故人西辭黃鶴樓,

煙花三月下揚州。

孤帆遠影碧空盡,

唯見長江天際流。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

黄 鹤 楼 送 孟 浩 然 之 广 陵

huáng hè lóu sòng mèng hào rán zhī guǎng líng

故 人 西 辞 黄 鹤 楼,

gù rén xī cí huáng hè lóu ,

烟 花 三 月 下 扬 州。

yān huā sān yuè xià yáng zhōu 。

孤 帆 远 影 碧 空 尽,

gū fán yuǎn yǐng bì kōng jìn ,

唯 见 长 江 天 际 流。

wéi jiàn cháng jiāng tiān jì liú 。

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Seeing off Meng Haoran for Guangling at Yellow Crane Tower Li Bai

My old friend departs the west at Yellow Crane Tower,

On a journey to Yangzhou among March blossom flowers.

His lonely sail receding against the distant blue sky,

All I see but the endless Yangtze River rolling by.

* * *

In the spring of 728 at age 27, Li Bai heard that Meng Haoran

was going to take a trip to Yangzhou 杨州. Li Bai managed to travel to present-day Wuhan city in Hubei Province 武汉市, 湖北省

to meet with Meng for several days of adventure, after which they parted at the nearby Yellow Crane Tower. Li Bai wrote this famous poem describing the melancholic nature of his idol's departure.

The poem is filled with affection and paints a vision of a brilliant spring day pushed to the horizon by the endless and powerful Yangtze River. It is a vision and a force that also carries away the ardent heart of the poet as he watches his idol's lone boat vanish into the distant horizon.

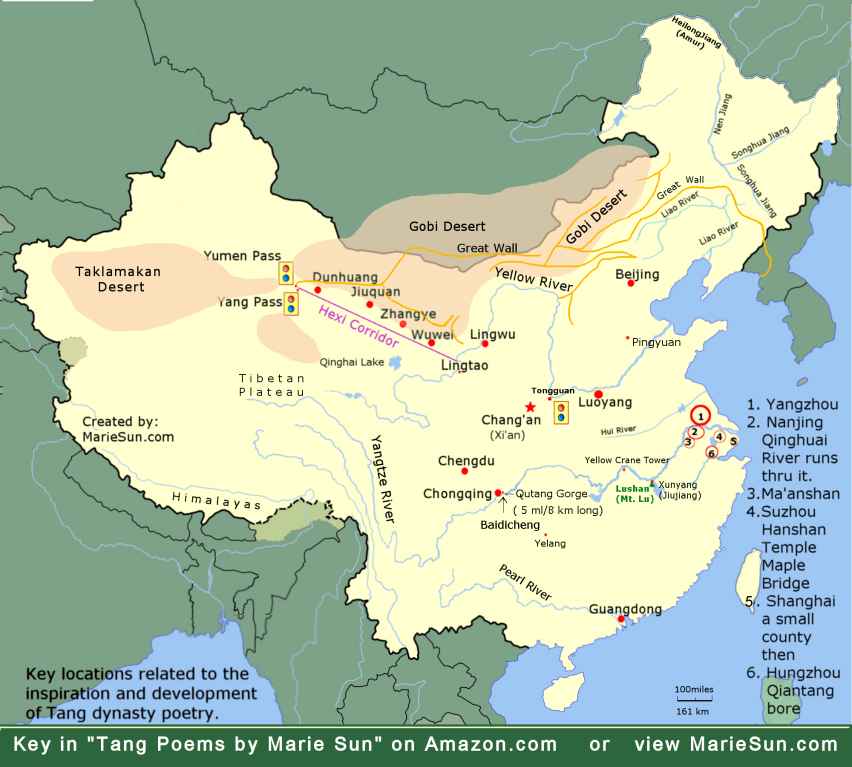

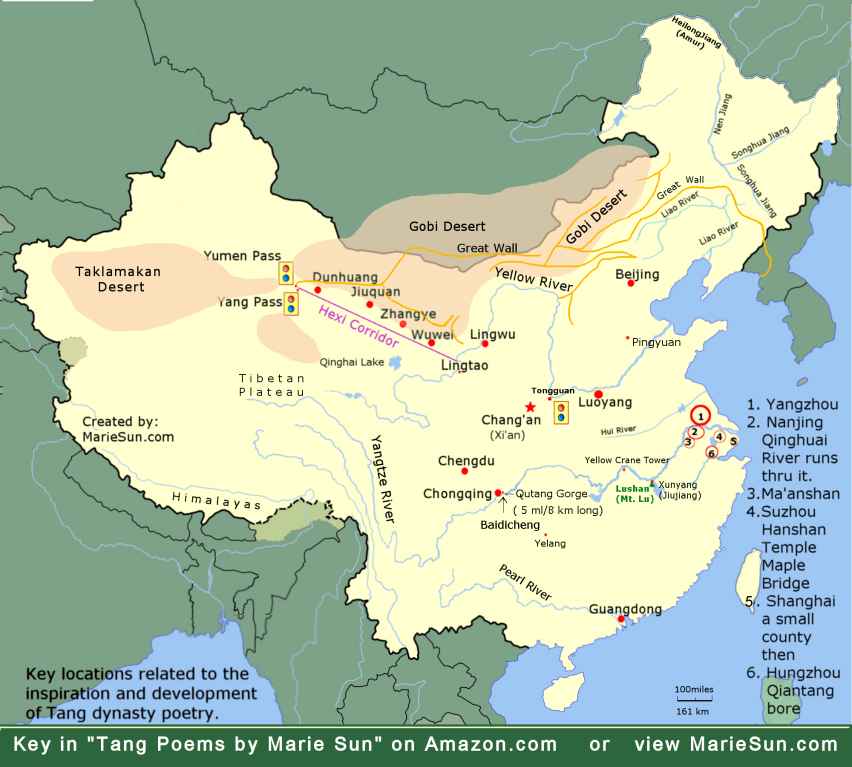

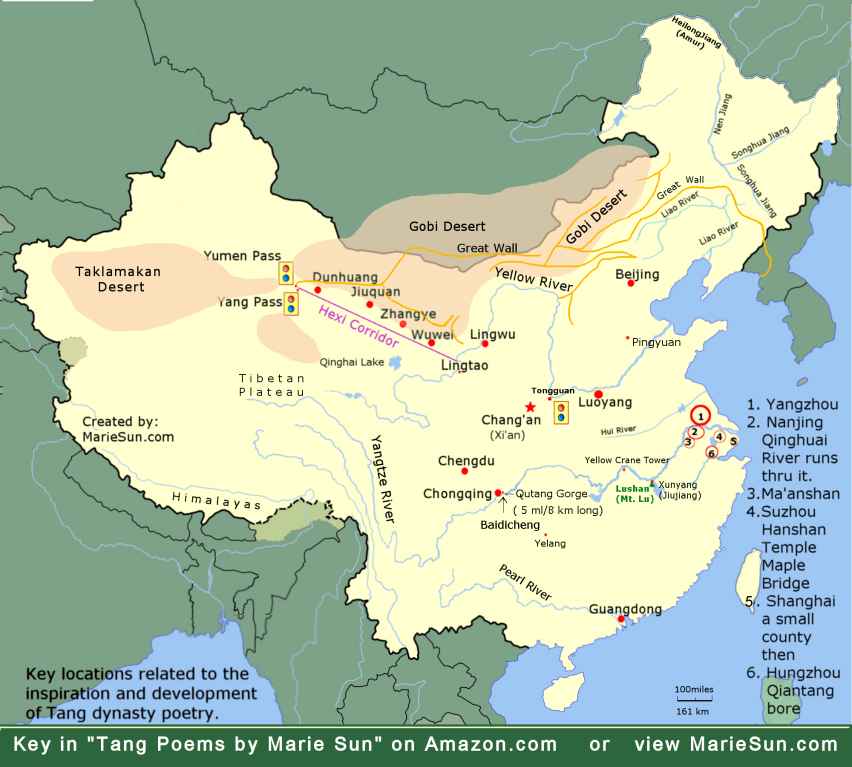

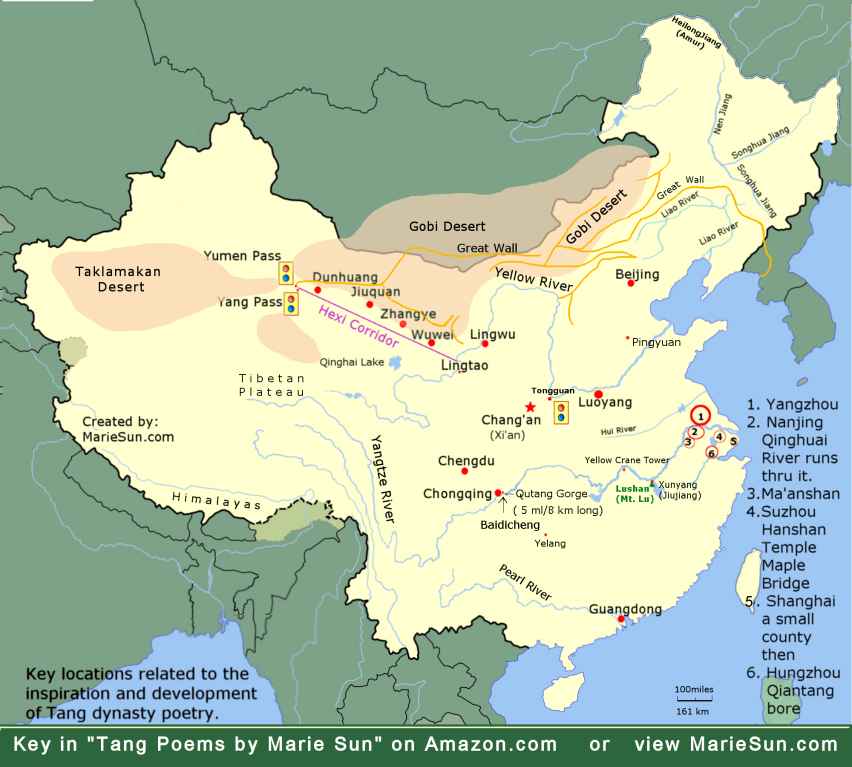

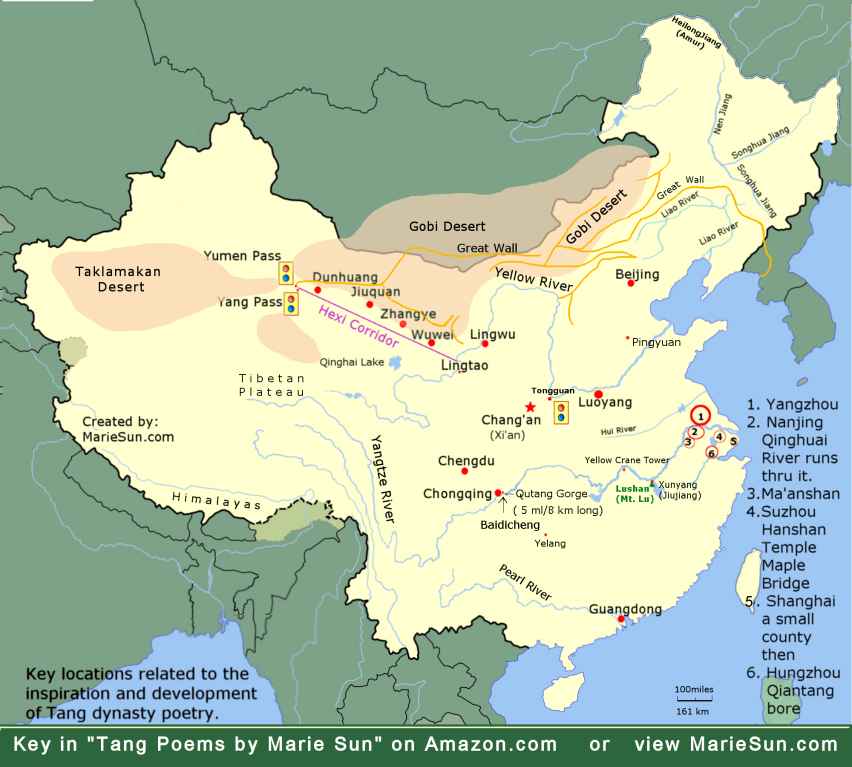

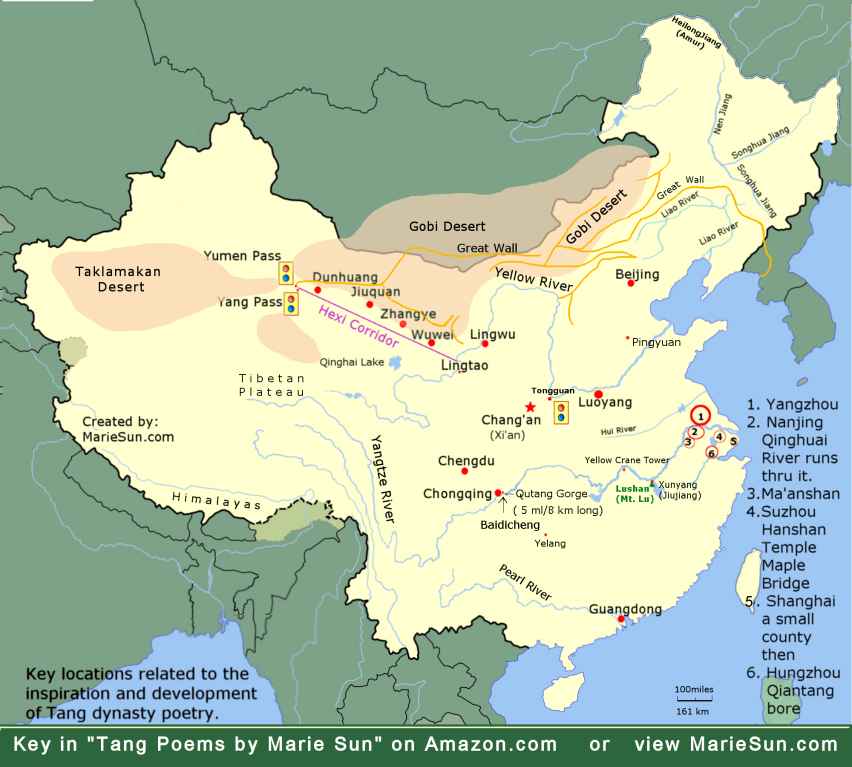

Yangzhou (marked as number 1) is located near the eastern terminus of the Yangtze River. The Yellow Crane Tower lies between Chongqing and Yangzhou by the Yangtze River.

(This map may be freely copied from www.mariesun.com for educational or noncommercial purposes of uses with a reference to "Marie Sun and Alex Sun" or at "MarieSun.com".)

The map's outline is provided by

Joowwww [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

广陵 Guangling: An old name for Yangzhou.

送: to see off , to send, to deliver, to carry, to give (as a present) , to present (with), 之: to

故人: old friend, the ancient 西: west

辞: to depart, to leave, to resign, to dismiss, to decline, to take leave, words, speech

烟花: full bloom of flowers, fireworks,

三月: March 下: going down, traveling down

孤: lone, lonely 帆: sail 远: far, distant, remote

影: shadow, picture, image, reflection,

碧空: the blue sky, the azure sky

尽: to the utmost, to end, to use up, to exhaust, to finish, exhausted, finished, to the limit (of something), to the greatest extent, extreme, within the limits of

唯: only, alone 见: to see, to meet

天际: horizon 流: to flow, to disseminate, to circulate or spread, to move or drift

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Meng Haoran visited the beautiful city of Yangzhou 扬州, which was the most prosperous city in the

Jiangnan 江南

region during the Tang Dynasty. "Jiangnan" literally means "River South", or "the Yangtze River South". Although Yangzhou lays on the north bank of the Yangtze River, northeast of present-day

Nanjing city, it became associated with the Jiangnan region by dint of its sheer wealth and prosperity.

The distance from Yellow Crane Tower to Yangzhou is about

330 mi/483 km (mi: miles, km: kilometers) as the crow flies, 460 mi/736 km as the river winds.

View Yangzhou thru Google,

Baidu,

Yahoo,

Yahoo JP,

Google Hong Kong,

or

Bing.

2. Being prosperous, Yangzhou has always been famous for its dessert dim sum:

View thru Google

or

Baidu.

3. They parted at the Yellow Crane Tower 黄鹤楼:

A famous, historical tower, it was first built in 223 AD, on Sheshan in the Wuhan, Hubei Province 武汊, 湖北省 by the Yangtze River. Warfare and fire destroyed the tower many times and it has been rebuilt several times.

View the tower as of today thru Google or

night scene thru Baidu.

4. Changjiang/Yangtze River 长江:

Also known as the Yangtze River 杨子江. It is the longest river in Asia, and the third longest in the world after the Nile and Amazon Rivers. It flows for about 3,900 mi/6,280 km from the glaciers of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau eastward across southwest, central, and eastern China before emptying into the East China Sea at Shanghai.

View thru Google,

Baidu,

Yahoo,

Yahoo JP

or

Bing.

5. Chinese calligraphy 黄鹤楼送孟浩然之广陵书法:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

#03 Qingping Song (1) 清平调词之一

Traditional Chinese

清平調之一 李白

雲想衣裳花想容, 春風拂檻露華濃。

若非群玉山頭見, 會向瑤臺月下逢。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

清 平 调 之 一 李 白

qīng píng diào cí zhī yī lǐ bái

云 想 衣 裳 花 想 容,

yún xiǎng yī shang huā xiǎng róng,

春 风 拂 槛 露 华 浓。

chūn fēng fú kǎn lù huá nóng.

若 非 群 玉 山 头 见,

ruò fēi qún yù shān tóu jiàn,

会 向 瑶 台 月 下 逢。

huì xiàng yáo tái yuè xià féng.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Qing Ping Ballad ( 1 ) Li Bai

A dress imagined by clouds,

A look imagined by flowers,

Spring breezes caress the threshold,

Lustrous dew showers;

If no meeting occurs at the cluster of Jade Mountain peaks,

Then rendezvous at Jade Pavilion in the moonlight hours.

* * *

This was written at Sinking Incense Pavilion 沈香亭 as Tang Ming Huang and

Yang Guifei wandered among the *peonies -- highly regarded ornamental flowers

in Chinese tradition. At Tang Ming Huang's request, Li Bai wrote three poems -- Qing Ping Ballads I, II and III

on that day. After each poem was completed, the court orchestra would accompany a chanting of it

for the audiences to enjoy. The multi-talented Tang Ming Huang also appreciated music and had a talent for composing, but unfortunately none of his works are extant.

In Qing Ping Ballad I, Li Bai metaphorically describes Yang Guifei's charms and the indulgent pampering she enjoyed from the emperor.

The locations that Li Bai describes in the poem - Jade Mountain and Jade Pavilion - were inhabited by fairies in Chinese folklore,

implying that Yang was a creature from an otherworldly realm. Yang had indeed been living in a fairy tale for 12 years,

indulging in an extremely extravagant life style, courtesy of Tang Ming Huang. What she could not have imagined was

the unexpected and tragic fate that awaited her.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

清 平 调 词 之 一: One of the Qing Ping Ballads 之 一: one of it

云: cloud 想: think, consider, speculate 衣裳: clothes 花: flower 容: looks, appearance, figure, form,

春风: spring winds 拂: brush away, shake off 槛: balustrade 露: dew, exposed 华: beautiful, flowery, illustrious, Chinese 浓: thick, strong, concentrated

若非: if not 群: group, crowd, multitude 玉: jade, precious stone, gem 山: mountain, hill

群玉山: In Chinese legend, this was the main Palace of the Queen Mother of the Western Paradise. Its name is due to the prolific jade deposits found in the mountain.

头: top, head, chief, first, boss 见: meet, see, perceive

会向: meet at 瑶: precious jade 台: pavilion, platform 瑶台: one of Queen Mother's palaces located in the legendary Kunlun Mountains.

月下逢: meet under the moon, implies romance in Chinese culture.

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Items and products produced and used in the Tang Dynasty:

View via Google ,

Yahoo or

Baidu.

2. Costumes in the Tang Dynasty:

View via Google or

Baidu.

3. Present-day entertainment world imitations of Tang clothing:

View via Google,

Yahoo or

Baidu.

4. *The peony 牡丹花 has been adored by all Chinese since ancient times.

It is not only considered a symbolic token of love by the Chinese, but is also believed to be a valuable medicinal plant. Chinese literati and poets have focused on the peony as the subject of a great many poems and brush paintings throughout history.

View peony via Google or

Baidu (Chinese brush paintings).

5. Chinese calligraphy 清平調之一书法:

View via Google or

Yahoo.

#04 Look Out Over Mount Lu Waterfall 望庐山瀑布

Traditional Chinese

望廬山瀑布 李白

日照香爐生紫煙,

遙看瀑布掛前川。

飛流直下三千尺,

疑是銀河落九天。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

望 庐 山 瀑 布 李 白

wàng lú shān pù bù lǐ bái

日 照 香 炉 生 紫 烟,

rì zhào xiāng lú shēng zǐ yān ,

遥 看 瀑 布 挂 前 川。

yáo kàn pù bù guà qián chuān 。

飞 流 直 下 三 千 尺,

fēi liú zhí xià sān qiān chǐ ,

疑 是 银 河 落 九 天。

yí shì yín hé luò jiǔ tiān 。

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Lookout over the Mount Lu Waterfall Li Bai

Sunlight illuminates the incense peak,

Sparking a purple haze,

I examine a distant waterfall

Hanging before the riverways;

Its flowing waters

Flying straight down three thousand feet,

I wonder -

Has the Milky Way been tumbling from heavenly space?

* * *

Li Bai's unrestrained imagination is fully expressed in the poem with concise, yet powerful words.

The mountain's scenery changes according to the season and is beautiful all year round, although summer is traditionally considered the best time of year to visit. A great many poets have been drawn to it to write about it since ancient times. Li Bai's "Lookout over the Mount Lu Waterfall" stands out among them all.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

望: to look at, look forward, to hope, expect 庐山: Mt. Lu/Lushan - a famous summer resort.

瀑布: waterfall, cascade

日: sun, day, daytime 照: shine, illumine, reflect 香: fragrant, sweet smelling, incense 炉: furnace, fireplace, stove, oven 生: produce, create, give rise to, cause, life, living, lifetime, birth 紫: purple, violet 烟: smoke, soot, opium, tobacco, cigarettes

遥: far away, distant, remote 看: look, see, examine, scrutinize 挂: hang, suspend, suspense 前: in front, forward, preceding 川: river, stream, flow, boil

飞: fly, go quickly, dart, high 流: flow, circulate, drift, class 直: straight, erect, vertical 下: under, underneath, below, down, inferior, bring down 三: three 千: thousand, hundreds and hundreds, a great many,

尺: a measure in length in China. One Chinese foot is about 1.094 feet.

疑: doubt, question, suspect 是: indeed, yes, right, to be, 银: silver, cash, money, wealth 河: river, stream, yellow river

银河: Milky Way, Galaxy 落: fall, drop, net income, surplus 九: nine 天: sky, heaven, god, celestial

九天: the highest heavens, the heaven of the Taoists.

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Due to geomorphological erosion, the waterfall at Mt. Lu obviously

is much less powerful and spectacular than at the time when Li Bai visited some 1,200 years ago. 庐山瀑布:

View Three Tiled Springs 三叠泉 thru baike.baidu.com/pic/%E4%B8%89%E5%8F%A0%E6%B3%89/70190/1275986/e6508eef91f928bfce1b3eb5?fr=lemma#aid=1275986&pic=e6508eef91f928bfce1b3eb5.

View Lushan Falls thru Google or

Yahoo.

2. Chinese calligraphy 庐山望瀑布书法:

view thru Google or

Yahoo.

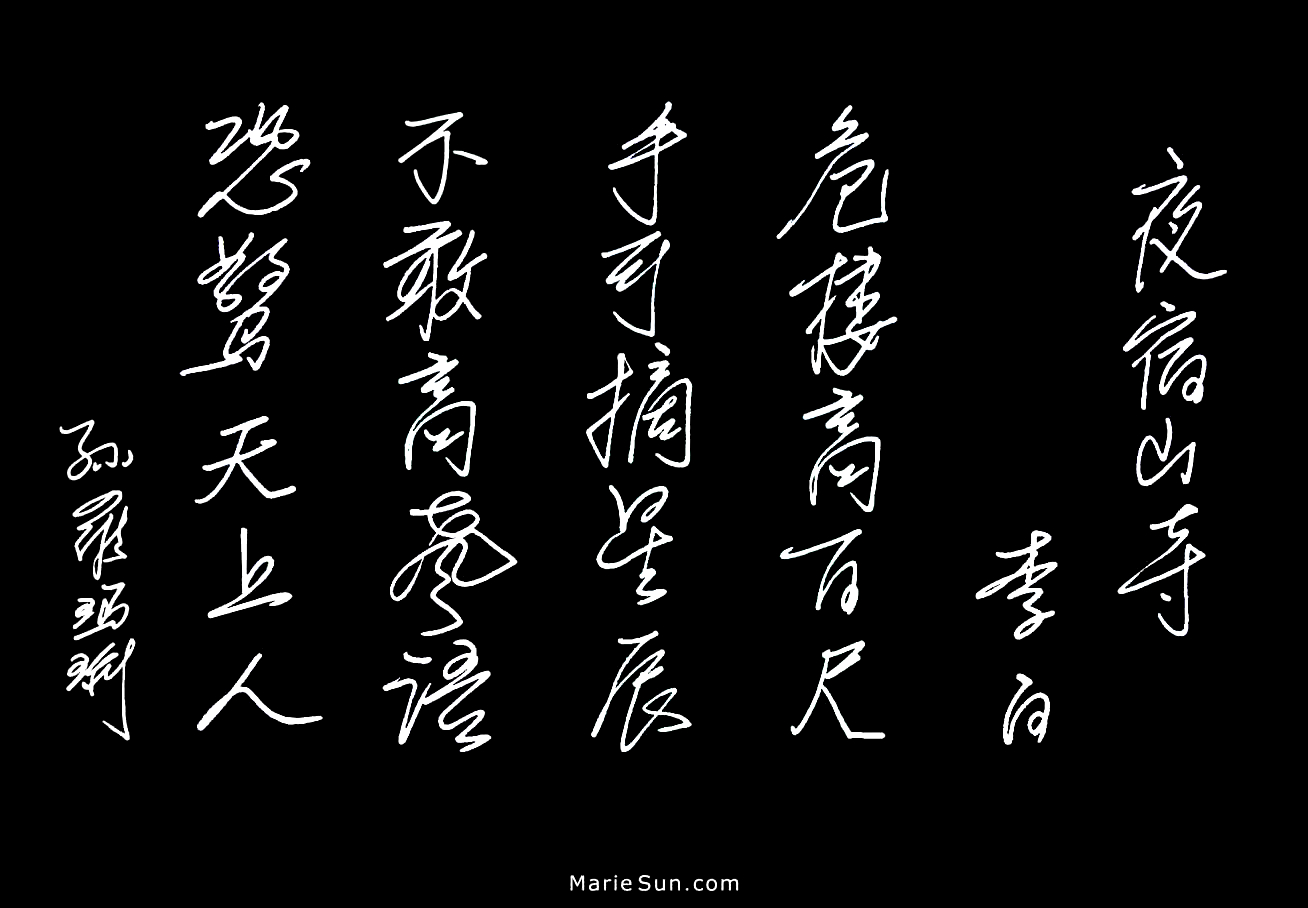

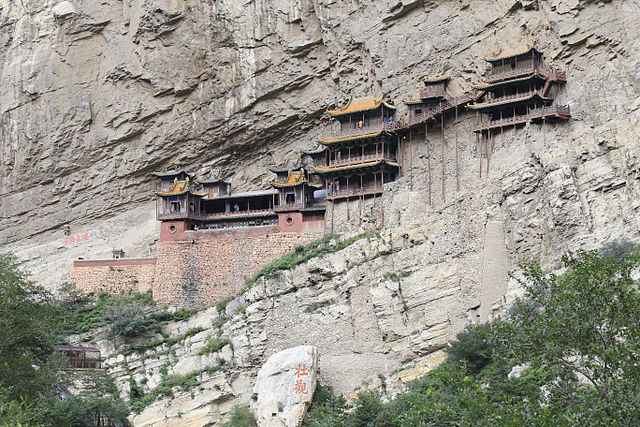

#05 Night Lodging in a Mountain Temple 夜宿山寺

Traditional Chinese

夜宿山寺 李白

危樓高百尺,手可摘星辰。

不敢高聲語,恐驚天上人。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

夜 宿 山 寺 李 白

Yè sù shān shì lǐ bái

危 楼 高 百 尺, 手 可 摘 星 辰。

wéi lóu gāo bǎi chǐ, Shǒu kě zhāi xīng chén.

不 敢 高 声 语, 恐 惊 天 上 人。

Bù gǎn gāo shēng yǔ, kǒng jīng tiān shàng rén.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Night Lodging in a Mountain Temple Li Bai

Atop a tremulous tower hundreds of feet high;

My hand can pick the stars.

I dare not let out a roar though;

For fear of startling the gods.

* * *

While traveling among the mountains, Li Bai spent most nights lodging at temples. This is one that he stayed at.

The poem is rich in its sense of romanticism and humor. In just a few strokes, it brings out joyous wonder, a sense of mischief, and boyish cuteness.

It reveals Li Bai's unrestrained, innocent, and carefree

personality.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

夜: night 宿: stay overnight

山: mountain, hill, peak 寺: temple, monastery, court, office

危: dangerous, precarious, high 樓: tower, building of two or more stories

高: high, tall, lofty, elevated 百: hundred, numerous, many 尺: a measure in length in China. One Chinese foot is about 1.094 English imperial feet.

手: hand 可: can, able, possibly 摘: pick, take, pluck 星: star, planet, any point of light 辰: early morning

星辰: star

不敢: dare not 高声: loud 语: talk, language, words, saying, expression

恐: afraid , frightened, to fear 惊: to be frightened, to be scared, alarm 天: heaven, god, celestial, sky

上: top, superior, highest, go up, send up 人: people, man, mankind, someone else

View the following images related to the poem:

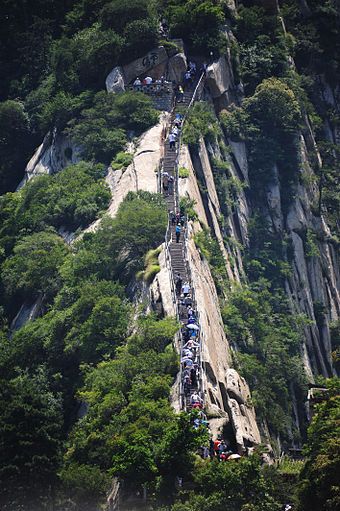

1. Pursuing a simple lifestyle is one of the basic precepts of Taoism; even its temples conform to this idea. Li Bai was a Taoist sympathizer, and we can sense this from some of his poems.

A Taoist temple on top of a mountain.

View thru DailyMail.com,

Google,

Baidu,

Bing or

Yahoo.

2. Chinese calligraphy 夜宿山寺书法.

view thru Google or

Baidu.

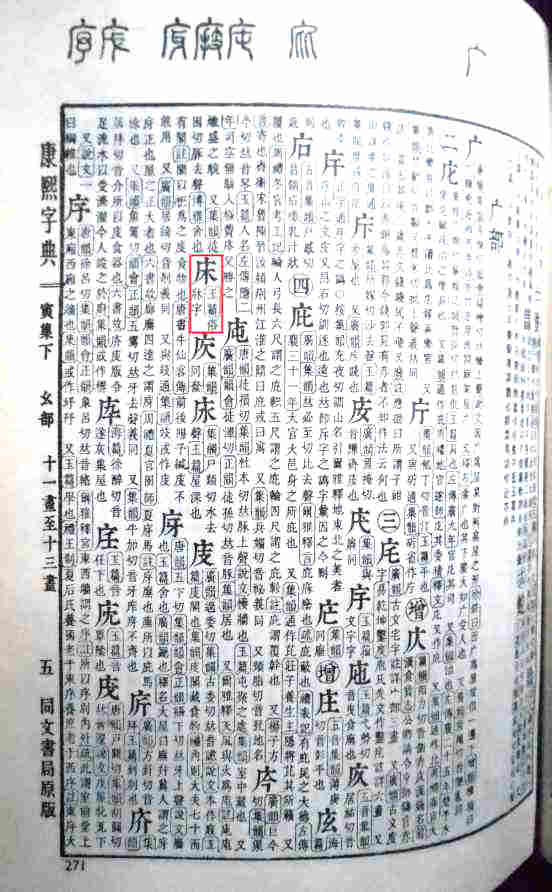

#06 Thoughts on a Still Night 靜夜思

Traditional Chinese

靜夜思 李白

床前明月光,疑是地上霜。

舉頭望明月,低頭思故鄉。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

靜 夜 思 李白

Jìng yè sī lǐ bái

床 前 明 月 光, 疑 是 地 上 霜。

chuáng qián míng yuè guāng, yí shì dì shàng shuāng。

举 头 望 明 月, 低 头 思 故 乡。

jǔ tóu wàng míng yuè, dī tóu sī gù xiāng 。

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Thoughts on a Still Night Li Bai

Before the well lays the bright moonlight,

As if frost blanketing the earth.

My head tilts upwards at the glowing moon;

My head lowers with thoughts of home.

* * *

While on a trip far away from home, Li Bai staring out on a moon-lit night, standing by a well in a courtyard, overcame with a melancholic sense of loneliness

and nostalgia. Such an event inspired him to pen his most famous poem -

"Thoughts on a Still Night". This is one of the most popular poems of all time that almost all Chinese can recite by heart.

Admiring and contemplating a bright, full moon, is a Chinese tradition, especially for a traveler away from home. Chinese believe that when people look at a bright, full moon, while alone on a tranquil night,

their thoughts will naturally wander towards their beloved ones.

Several famous classical verses reflecting this popular conception include:

海上生明月,天涯共此時。-

When the bright moon breaks the surface of the sea,

All under heaven are one at this moment.

明月千里寄相思 -

The bright moon carries lovesickness a thousand miles (to reach a beloved one).

月是故鄉明 -

The moon is brighter over home (implies thinking about and missing beloved ones back in one's hometown.)

The moon represents a direct, shared spiritual connection, as it would be assumed that no matter what the physical distance was separating them, beloved ones would or could all be looking at the exact same moon at the exact same time, sharing the same thoughts of far away beloved ones in their hearts.

Li Bai's "Thoughts on a Still Night" has stirred feelings of homesickness in countless Chinese caught traveling far away from home on silent, moonlit nights, since the Tang Dynasty.

Why is the character "床" (sleeping bed, the structure of ...) translated as "well" in the poem?

While many school children (and translators!) take the Chinese character 床 to mean "bed" in its modern sense, it is more likely to refer to "the structures around a well" in its ancient sense. Ancient Chinese windows were often framed with decorative carvings

or/and overhead eave-like structures - specifically

to provide shading from sunlight (and prevent break-ins, as they could be shut and locked), but consequently also equally adept at preventing moonlight from entering a room.

It would thus seem unlikely that light could have entered a bed room expansively enough to be mistaken as frost by the bedside.

It is more likely that Li Bai was referring to the platform structure or fence skirting a well, which was an alternate ancient meaning of 床.

Li Bai also wrote another famous poem "Chang Gan Xing" "长干行" employing the character 床 in the sense of a wood structure surrounding a well -

Just starting to wear my hair banged,

I plucked flowers playing by the door.

He came on bamboo hobby-horse to the scene;

Circling the "well"

and pinching plums green.

Neighbors we were in Changgan alley,

Two little ones so trusting and carefree.

.

.

.

妾发初覆额,折花门前剧。

郎骑竹马来,绕

"床" 弄青梅。

同居长干里,两小无嫌猜。

.

.

.

There is no doubt that the "bed"

"床" here never meant a bed for sleeping.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

靜 : quiet, still, calm, not moving 夜: think 思: to think, to consider

前: front, forward, ahead, ago, before, first, former, formerly

明月: bright moon 光: light, ray,

疑: to doubt, to suspect 是: is, are, am, yes, to be 地上: on the ground, on the floor

霜: frost, white powder or cream spread over a surface, frosting, (skin) cream

舉: to raise, to lift, to hold up 頭: head, the top, chief, boss, first, leading

望: to gaze (into the distance) , to look up, to look towards

低頭: to bow the head, to yield, to give in, to look down

思: to think, to consider 故鄉: home, homeland, native place

View the following images:

1. View architectural window style in Tang Dynasty

thru

Google or

Baidu.

2. View architectural window style in ancient China thru

Google or

Baidu.

3. View a well with a surrounding platform

thru Google

or

Yahoo.

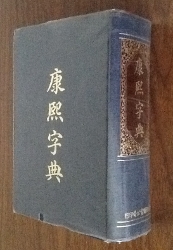

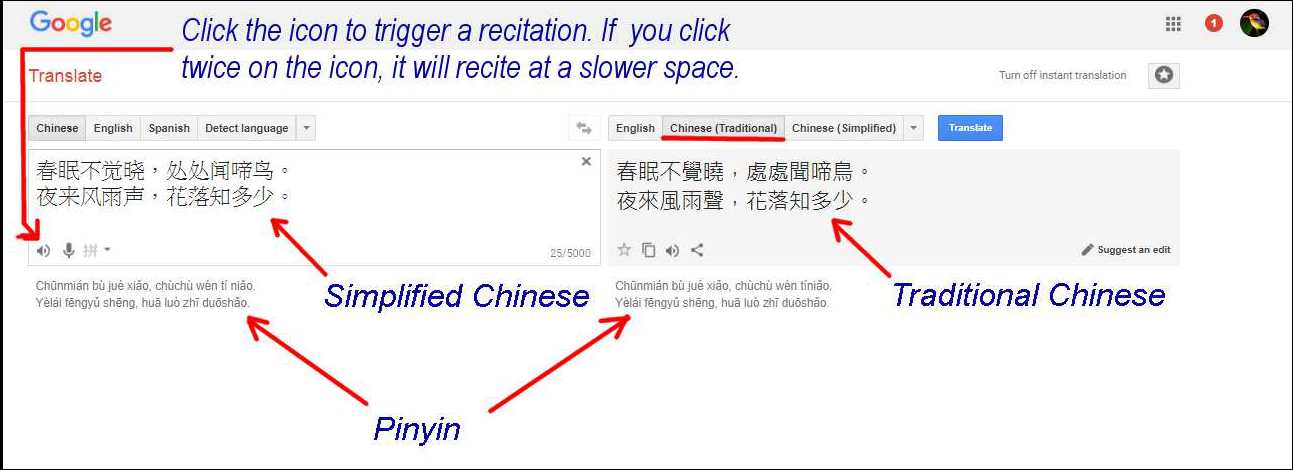

4.

Search results from the

Kangxi Dictionary 康熙字典 (Wikipedia)

about "bed" "床":

"床" means both:

(1) a bed for sleeping or,

(2) a structure around a well.

The character for "bed" 床 can also be written as 牀.

"又井榦曰牀" - "Again, the wooden structure around a well is called a bed".

"後園鑿井銀作牀" - "To dig a well in the back garden and fence it with stakes or other structures."

5. Chinese calligraphy 靜夜思书法:

view thru Google or

Yahoo.

#07 Drinking Alone by Moonlight 月下独酌

Traditional Chinese

月下独酌 李白

花間一壺酒,独酌無相親;

舉杯邀明月,對影成三人。

月既不解飲,影徒隨我身;

暫伴月將影,行樂須及春。

我歌月徘徊,我舞影零亂;

醒時同交歡,醉后各分散。

永結無情遊,相期邈雲漢。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

月 下 独 酌 李 白

yuè xià dú zhuó lǐ bái

花 间 一 壶 酒, 独 酌 无 相 亲;

huā jiān yī hú jiǔ, dú zhuó wú xiāng qīn,

举 杯 邀 明 月, 对 影 成 三 人。

jǔ bēi yāo míng yuè,duì yǐng chéng sān rén.

月 既 不 解 饮, 影 徒 随 我 身;

yuè jì bù jiě yǐn,yǐng tú suí wǒ shēn,

暂 伴 月 将 影, 行 乐 须 及 春。

zàn bàn yuè jiāng yǐng,xíng lè xū jí chūn

我 歌 月 徘 徊, 我 舞 影 零 乱;

wǒ gē yuè pái huái, wǒ wǔ yǐng líng luàn

醒 时 同 交 欢, 醉 后 各 分 散。

xǐng shí tóng jiāo huān, zuì hòu gè fēn sàn

永 结 无 情 游, 相 期 邈 云 汉。

yǒng jié wú qíng yóu, xiāng qī miǎo yún hàn

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Drinking Alone by Moonlight Li Bai

A jug of wine amidst the flowers,

I drink alone with no soul around.

I raise my wine cup to the moon and invite her down;

Now we are three with my shadow.

The moon, she does not drink,

And my shadow follows my every move;

But for the moment,

The moon is my partner and I hang with my shadow.

To enjoy life is to take advantage of youth.

I sing, the moon hovers all around;

I dance, the shadow follows in a messy stumble.

Lucid, we enjoy each other knowingly;

In drunken sleep, we go our separate ways.

Bound to forever travel carefree,

We shall meet again in cosmic paradise.

* * *

Li Bai was a wine lover. Wine seemed to be catalyst that could ignite his poetic prowess with such speed

that he could reportedly pen a poem in a matter of seconds after a few drinks. Thus, he was accorded the name of Jiouxian 酒仙, literally, "wine immortal."

As a wine connoisseur he wrote numerous poems on the subject. "Drinking Alone by Moonlight" is one of the most famous among all

"wine poems" written by East Asian poets through the ages. Induced by just a jug of wine, Li Bai dances into a fanciful world; and by the magic of his pen brush, he brings the reader along with him into his fantastical reverie.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

月: moon, month

月下: under the moon

独酌: drinking alone

其 一 : article 1, page 1 one of ..., poem 1 of ...

花間: amidst the flowers

壶: jug, pot, kettle

一壶酒: a jug of wine

无: not to have, no, none, not, to lack

相親: to be deeply attached to each other

舉杯: to toast (with wine etc), to drink a toast 邀: to invite, to request, to intercept, to solicit, to seek

明月 : bright moon 对: couple, pair, right 影: shadow, picture, image, film, movie, photograph, reflection

对影: pair with the shadow

成: to become, to turn into, to complete, to accomplish, to be all right, OK!

既: since, already 不解: to not understand, to be puzzled by, indissoluble 饮: to drink

徒: to no avail, only, disciple, apprentice, on foot, bare or empty

隨: to follow, to comply with, varying according to...

我: I, me, my 身: body

暂: temporary

伴: partner, companion, comrade, associate, to accompany

将影: 将就影子 go along with the shadow

行乐: have a good time, 须: must, to have to 及: in time for, and, to reach, up to 春: youthful, springtime, joyful, lust 及春: catch the moment while still in youth, catch the moment of the spring

歌: song, to sing 徘徊: to hover around, to linger, to hesitate, to pace back and forth

舞: dance 零乱: in disorder, a complete mess

醒: to wake up, to awaken, to be awake 时: time 同: together, like, same, similar, alike, with 交欢: to have cordial relations with each other, to have sexual intercourse

醉: intoxicated, drunk 后: after, afterwards, back, behind, rear, later 各: each, every 分散: to scatter, to disperse, to distribute

永: forever, always, perpetual 结: knot, sturdy, bond, to tie,

无情: pitiless, ruthless, merciless, heartless.

无情: here can be interpreted as 忘情 (忘卻世俗之情, 不动感情, 淡然处事) which means to ignore the secular rules, to be carefree, to be unruffled by emotion, to be unmoved, to be indifferent, to not take things seriously, without a worry and care in the world

游: to travel, to walk, to tour, to roam, to swim

相期: expect to meet

邈: far, distant, remote, slight

云漢: heaven, Milky Way, land of divine, place of exquisite natural beauty

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Cups and vessels in the Tang Dynasty 唐代酒具 (In the Tang Dynasty, Chinese rarely used glass for wine or beverages, as glass was rare at that time): View wine cups thru Google,

wine vessels thru Baidu or Yahoo.

2. Luminous cup 夜光杯 - another wine vessel made of jade in the Tang Dynasty:

View thru Google or

Baidu.

3. Chinese calligraphy 月下独酌书法: view thru Google or Yahoo.

#08 Setting out Early from Baidicheng 早发白帝城

Traditional Chinese

早發白帝城 李白

朝辭白帝彩雲間,

千里江陵一日還。

兩岸猿聲啼不盡,

輕舟已過萬重山。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

早 发 白 帝 城 李白

Zǎo fā bái dì chéng lǐ bái

朝 辞 白 帝 彩 云 间,

zhāo cí bái dì cǎi yún jiān,

千 里 江 陵 一 日 还。

qiān lǐ jiāng líng yī rì huán.

两 岸 猿 声 啼 不 尽,

liǎng àn yuán shēng tí bù jìn,

轻 舟 已 过 万 重 山。

qīng zhōu yǐ guò wàn chóng shān.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Setting Out Early from Baidicheng Li Bai

With Baidi enshrouded in tinted clouds,

I left at early dawn,

Returning a thousand miles to Jiangling

in a day.

While the sounds of apes roared endlessly from both sides of the riverbanks,

My light skiff has already sailed past a myriad of mountains.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

早: early, morning, Good morning! 發: to send out

白帝城: An ancient temple located on a hill on the north shore of the Yangtze River to the east side of Chongqing, Sichuan Province, 重庆, 四川省.

(note: some characters have more than one pronunciation and have completely different meanings when set in compound words. Here, only the most obvious and contextually logical meanings are provided)

Two ways to pronounce 朝:

(1). zhāo - morning, day,

morning sun 朝陽, day and night 朝夕

(2). cháo - a dynasty 朝代, an imperial court 朝廷, to be received in audience by a sovereign 朝見

辞: to take leave, to resign, to dismiss, to decline 彩云: rosy clouds

间: in the middle of

千: thousand, a great many

里: also called huali 华里, a measurement of distance in China. The length of a "li" 里 has varied during the course of China's long history. Traditionally, one li was equal to about 0.31 English imperial miles or 0.5 kilometer. Thus, 1,000 li is about 310 mi/500 km.

江陵: a city's name.

一日: one day

还: return, arrive

两: two

岸: bank, shore, beach, coast

猿声啼: the sound of ape's roaring

不尽: not stop, endlessly

(Some versions use 两岸猿声啼不 "住" instead of 两岸猿声啼不 "尽"; both have the same meaning.)

轻: light, easy, gentle, soft, unimportant, small in number

舟: skiff, boat

过: pass through

已过: has passed through

万: ten thousand, thousands and thousands, a great many

Two ways to pronounce 重:

(1). chóng: repeat, repetition, again -

万重山: tens of thousands of mountains, thousands of thousands of mountains, numerous mountains;

重覆: repeat

(2). zhòng: heavy -

重要: important,

重量: weight

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Vistas scattered along the Yangtze River tracing Li Bai's journey from Baidicheng to Jiangling:

(1). Baidicheng 白帝城: The name literally means "City of the White Emperor".

View thru Baidu

or

Google.

Baidicheng faces the western entrance of the Qutang Gorge and Kui Gate 瞿塘峡 和 夔门 with an awesome spectacular view.

View thru Baidu or

Google.

(2). The Ancient Plank Road around the Qutang Gorge 瞿塘峡古栈道:

View thru Google or

Baidu.

(3). Hanging coffins 悬棺 on cliffs along the Qutang Gorge near Baidicheng:

View thru Google,

Baidu,

Bing

or

Yahoo.

(4). Solve the puzzle -- how were the hanging coffins placed on the soaring cliff faces thousands of years ago (some were placed 3,000 years ago)?:

View thru YouTube (25 minutes with English captions)

(thru YouTube 2:10 minutes)

or

select one from the YouTube videos.

(5). Jiangling 江凌: present-day Jingzhou city, in Hubei Province 荊州市, 湖北省 on the north shore of the Yangtze River. It served as the capital of several small kingdoms in ancient China. Under the Tang Dynasty, it served as the southern capital and was known as Nandu 南都.

View historic site thru Google

or

Baidu.

2. Chinese calligraphy 早发白帝城书法:

view thru Google or

Yahoo.

Li Bai wrote the following four poems years before he went into exile to Yelang.

#09 Sitting Alone at Mt. Jingting 独坐敬亭山

Traditional Chinese

獨坐敬亭山 李白

眾鳥高飛盡, 孤雲獨去閑。

相看兩不厭, 唯有敬亭山。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

独 坐 敬 亭 山 李 白

dú zuò jìng tíng shān lǐ bái

众 鸟 高 飞 尽, 孤 云 独 去 闲。

zhòng niǎo gāo fēi jìn, gū yún dú qù xián.

相 看 两 不 厌, 唯 有 敬 亭 山。

xiāng kàn liǎng bú yàn, wéi yǒu jìng tíng shān .

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Sitting Alone on Jingting Mountain Li Bai

Flocks of birds soar out of sight;

A lone cloud wanders away at leisure.

Not minding each other's tender glances,

All that remains is Jingting Mountain!

* * *

Jingting Mountain 敬亭山 is located north of Xuanzhou city in Anhui Province 宣州城, 安徽省, by the Shuiyang River 水阳江.

Li Bai visited the mountain at least seven times and wrote many poems about it -- this being the most famous one.

The mountain is actually a small range that contains about 60 peaks and sub-peaks and stretches for about 3 miles. The main peak is

about 300 meters above sea level. A multitude of scenic spots, springs, streams, and pavilions dot the mountain, and it was a famous resort during the Tang Dynasty.

Its picturesque scenery has been the the frequent subject of poetry and artwork.

The nearby city of Xuanzhou has been famous for its xuan paper 宣紙

since the Tang Dynasty. Today it is the major wholesale center for xuan paper. Xuan paper is renowned for being soft

and finely textured, suitable for both Chinese calligraphy and painting.

In 753, Li Bai visited Jingting Mountain by himself. Upon arriving, he noticed the chirping birds had all already left, and the clouds had all wandered away. Rather than finding himself alone and abandoned,

Li Bai viewed the verdant mountain itself like a living creature and dear companion. Thus, in any situation, he could always always find and see enjoyment.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

独坐: sit alone

众:multitude, crowd, masses 鸟: bird 高: high, tall, lofty, elevated 飞:fly, go quickly, dart, high 尽: exhaust, use up, deplete

孤: lone, lonely 云: cloud 独: alone, single, sole, only 去: to go, to go to (a place), to cause to go or send , to remove, to get rid of 閑 : stay idle, to be unoccupied, not busy, leisure

相看: to look at one another, to look upon 兩: two, both 不厭: not tire of, not object to

唯: only, 有: have, has

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Jingting Mountain 敬亭山:

View thru Baidu

or

Google .

2. Chinese calligraphy 敬亭山书法:

view thru Google or

Yahoo.

#10 Present to Wang Lun 赠汪伦

Traditional Chinese

贈汪倫 李白

李白乘舟將欲行,忽聞岸上踏歌聲。

桃花潭水深千尺,不及汪倫送我情。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

赠 汪 伦 李 白

Zèng wāng li bái

李 白 乘 舟 将 欲 行,

lǐ bái chéng zhōu jiāng yù xíng,

忽 闻 岸 上 踏 歌 声。

hū wén àn shàng tà gē shēng 。

桃 花 潭 水 深 千 尺,

táo huā tán shuǐ shēn qiān chǐ ,

不 及 汪 伦 送 我 情。

bù jí wāng lún sòng wǒ qíng 。

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Presented to Wang Lun Li Bai

Getting on board and ready to go,

Suddenly I heard the stomping and singing sound from the shore.

The Peach Blossom Pond is a thousand feet deep,

Yet not as deep as the friendship Wang Lun showed at my departing.

* * *

In 755 at age 54, Li Bai traveled to Peach Blossom Pond, Jing county, Anhui Province 桃花潭, 泾县, 安徽省.

The day before Li Bai's departure, Wang Lun, a commoner friend of his, had thrown a farewell party for Li and told him that he would be unable to see him off the next morning due to another appointment.

Actually Wang Lun had planned a big surprise farewell send-off for Li Bai by organizing a group of friends to chant poems on the

shore right before Li Bai's departure.

In ancient China, people chanted poems, in similar fashion as did the ancient Greeks with their odes, as opposed to simple readings or recitations. This poem reveals just how much the custom of chanted poems had permeated all segments of society during the Tang Dynasty.

The verses "The Peach Blossom Pond is a

thousand feet deep, yet not as deep as the friendship Wang Lun showed at my departing" "桃花潭水深千尺,不及汪伦送我情" has since long been used to describe the feelings between sincere friends who are parting.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

赠: to give as a present 汪伦: a friend of Li Bai

李白: our famous Tang poet 乘: ride: amount 舟: boat 将: will, shall 欲: desire, appetite, passion, lust, greed

There are two ways to pronounce 行 in Mandarin, each with different meanings:

(1). xíng -

to go, to travel, capable, competent, all right, OK!, will do. Examples -

He can do it, He's able to do it: 他行 tā xíng.

pedestrian: 行人 xíng rén

A type of Chinese calligraphy: 行书 xíng shu

planet: 行星 xíng xīng

do charitable work: 行善 xíng shàn

behavior: 行为 Xíng wéi

(2). háng -

rank, file, store, situation. Examples -

a line of ducklings: 一行小鸭

three lines of cars: 三行车队

bank: 银行 yín háng

expert: 行家 háng jiā

market quotations: 行情 háng qíng

shop, store: 行号 háng hào

How this line "一行行人" should be read:

一行 (háng) 行 ( xíng) 人, yī háng xíng rén: a line of pedestrians

忽闻: to hear suddenly, to learn of something unexpectedly 岸上: ashore 踏: to tread, to stamp, to step on, to press a pedal 歌声: singing voice, chanting poem

桃: peach 花: flower, blossom 潭: deep pool, pond 桃花潭: Peach Blossom Pond, located at present-day Jing county, Anhui Province 泾县, 安徽省.

水深: depth of waterway 千: thousand, hundreds and hundreds, a great many

尺: a measure of length in China equal to about a foot. One Chinese foot is about 1.094 English imperial feet.

不及: to fall short of, not as good as

送: to see off, to deliver, to carry, to give (as a present), to present (with), to send

我: I , me 情: passion, feeling, emotion

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Peach Blossom Pond in present-day Jing county, Anhui Province.

桃花潭:

View thru Google or

Baidu.

2. Chinese calligraphy 赠汪伦书法:

view thru Google or

Yahoo.

#11 Longing in Spring 春思

Traditional Chinese

春思 李白

燕草如碧絲, 秦桑低綠枝;

當君懷歸日, 是妾斷腸時。

春風不相識, 何事入羅幃?

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

春 思 李 白

chūn sī lǐ bái

燕 草 如 碧 丝, 秦 桑 低 绿 枝;

yàn cǎo rú bì sī, qín sāng dī lǜ zhī;

当 君 怀 归 日, 是 妾 断 肠 时。

dāng jūn huái guī rì, shì qiè duàn cháng shí.

春 风 不 相 识, 何 事 入 罗 帏?

chūn fēng bù xiāng shí, hé shì rù luō wéi

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

Longing in Spring Li Bai

Yan grasses like strands of emerald jade silk,

Qin mulberries weighing down branches green.

The day when your sire thinks of coming home,

Is when this lady's heart will be dying in tortured waiting.

O! Spring breeze - I dare not know you,

Why slip into the silk curtain surrounding my bed?

* * *

Li Bai uses symbolic imagery to delicately portray the

mood of a young woman

whose amorous feelings are aroused by the onset of spring,

but who has no way to satisfy them, except through a deep yearning for

her husband stationed far away. Yet a

gently, titillating spring breeze blows into her bedroom to

tease and arouse her even more.

Li Bai could be said to have had an intricate and precise understanding of women.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

春思: longing in spring

燕: Yan, located in present-day northern Hebei 河北 Province and western Liaoling 辽宁 Province -- the frontier in the Tang Dynasty. Hundreds of thousands of soldiers were stationed there, including, no doubt, the husband of the young lady in the poem.

草: grass, lawn, straw 如: as, as if, such as , 碧丝: green jade, bluish green, blue, jade, blush green silk, blue silk

秦: Qin, located in present-day Shanxi 陕西 Province. During the Tang Dynasty, a great many soldiers were drafted from this area and sent to

the bordering Yan area to guard the country.

桑: mulberry 低: low, beneath, to lower (one's head), to let droop, to hang down, to incline 绿枝: green branch

当: when, to be, to act as, during 君: you (a respectful form of address towards a man), monarch, lord, gentleman, ruler 怀: to think of, mind 归日: return day

是: is, are, am, yes, to be 妾: a polite term used by a woman in olden days to refer to herself when speaking to her husband, concubine

断肠: heartbroken. However, in the poem, it may imply to be heart-pounding, like butterflies in the stomach 时: time, o'clock

春风: spring breeze, good education, happy smile, sexual intercourse 不: no, not 相识: acquaintance, to get to know each other

何: what, how, why, which 事: matter, thing 入: to enter, to go into, to join 罗帏: curtain of thin silk (around the bed), women's apartment, tent

View the following images related to the poem:

1. Locations that the young wife's husband might have been deployed to and stationed:

(1). The Great Wall garrison bases in Hebei Province 河北长城戍地:

View thru Google or

Baidu.

or

(2). The Great Wall garrison bases in Liaoning Province 辽宁长城戍地:

View thru Google,

Baidu or

Yahoo.

2. Mulberry 桑 (the mulberry leaves are the sole food source for the silkworm.):

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

3. Chinese calligraphy 春思书法:

View thru Google or

Yahoo.

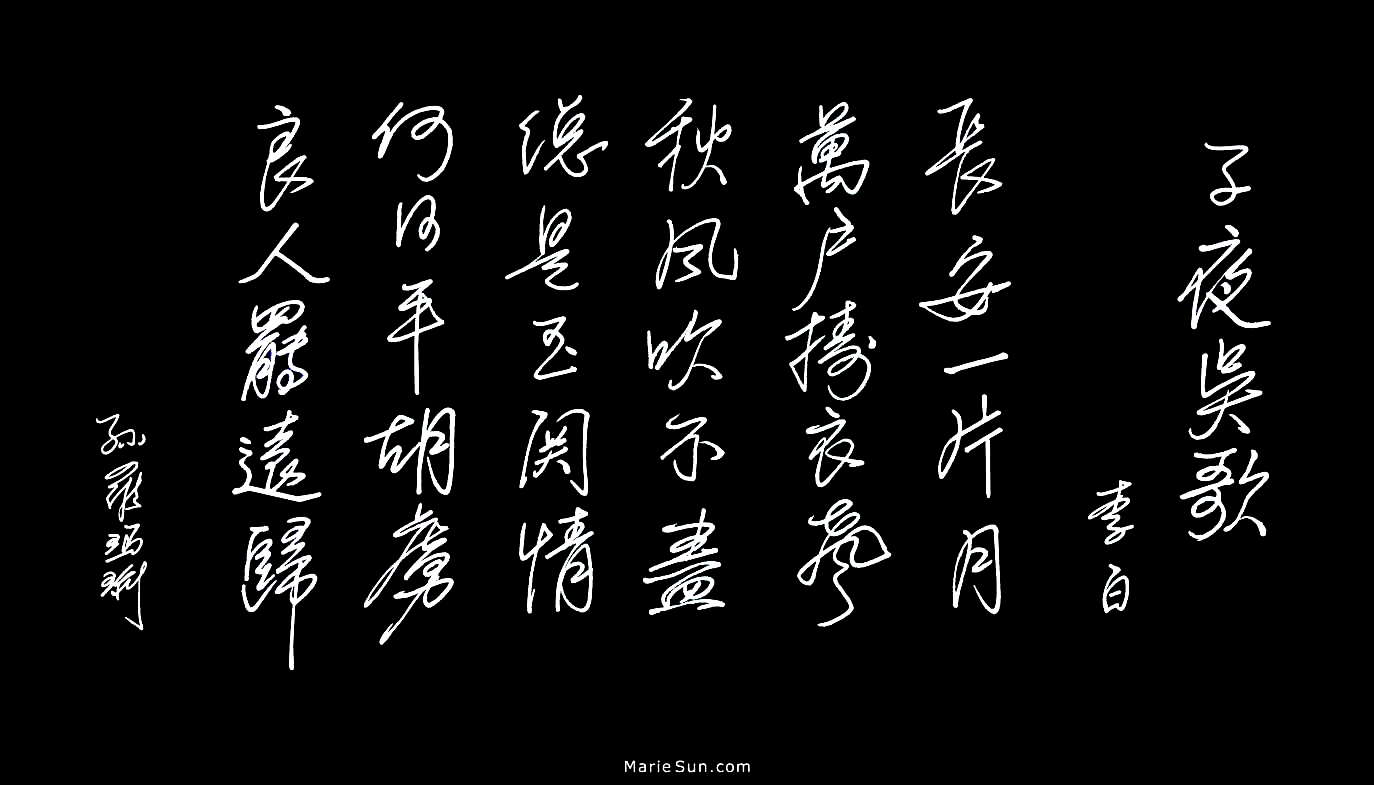

#12 A Midnight Wu Song for Autumn 子夜吴歌

Traditional Chinese

子夜吳歌 - 秋歌 李白

長安一片月,萬戶擣衣聲。

秋風吹不盡,總是玉關情。

何日平胡虜,良人罷遠征。

Simplified Chinese with pinyin

子 夜 吴 歌 - 秋 歌 李 白

zǐ yè wú gē - qiū gē lǐbái

长 安 一 片 月, 万 户 捣 衣 声。

cháng'ān yī piàn yuè, wàn hù dǎo yī shēng.

秋风吹不尽, 总是玉关情。

qiū fēng chuī bù jìn, zǒng shì yù guān qíng.

何日平胡虏, 良人罢远征。

hé rì píng hú lǔ, liáng rén bà yuǎn zhēng.

Recitation 1

Recitation 2

A Midnight Wu Song for Autumn Li Bai

Chang'an is framed by the moon,

Sounds of cloth pounding in a myriad homes.

The autumn winds blow without end,

Laying emotions ever at Jade Gate.

When will the Huns be pacified?

So that our men may quit their distant campaign.

* * *

The purpose of pounding fabrics was to render the course textile softer for easier sewing.

This is a famous painting -- "Pounding Fabrics Painting" "捣练图" - created by court painter Zhang Xuan 张萱 in the Tang Dynasty.

(source:

ru.wikipedia(Original text : MFA Boston),公有領域,https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=7855380).

View other images of pounding fabrics in China

thru Google or

Baidu.

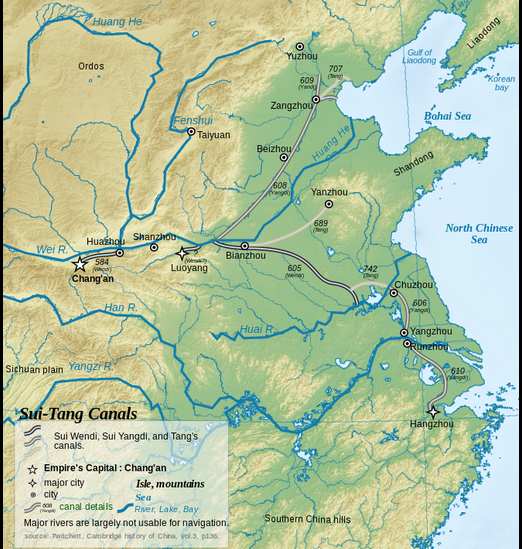

* * *

During the High Tang period, the royal court constantly deployed heavy military brigades to remote frontier regions to guard the border. The Jade Gate/Yumen Pass was situated in one of the major frontier areas. Autumn was the season in which the government always organized extra postal dispatches to help families deliver winter clothes to their beloved ones stationed in these areas. On a moon-lit night, the chilly autumn wind would carry the pounding sound, along with deep longings and blessings, from Chang'an all the way to the Jade Gate - the strategic military stronghold at the westernmost extension of

the Great Wall.

Definitions and Interpretation of Characters, Terms, and Names:

子夜: midnight 吴歌 the name of a tune in the Tang Dynasty which can be traced back to the state of Wu; therefore, it is also called Wu 吴 song 歌.

长安: Chang'an, the capital of Tang, present-day Xi'an city in Shanxi Province 西安市, 山西省 一: one, a, an, alone 片: slice, splinter, strip 月: moon; month

万: ten thousand, thousands and thousands, a great many, innumerable 户: door, family 捣: beat, attack, hull, thresh 衣: clothes, clothing, cover

捣衣:

1. to pound rough cloth, making it soft before sewing, usually with little or no water in the process.

2. to launder clothes by soaking them in water and then pounding them.

声: sound, voice, noise, tone, music

秋: autumn, fall 风: wind, air, manners, atmosphere 吹: blow, puff, brag, boast 不: not, no, negative prefix

尽: exhaust, use up, deplete 不尽: endlessly, not completely

总: overall, altogether, collect 是: is, yes, right, indeed 玉: jade, precious stone, gem 关: frontier pass, close, relation

玉关 also known as 玉门关 Yumenguan, Yumen Pass, or Jade Gate

情: feeling, sentiment, emotion

何: when, what, why, where, which, how 日: day, daytime, sun 何日: when? 平: flat, level, even, peaceful

胡虏: the various northern tribes, often referred to generally as Huns/Xiongnu 匈奴 or sometimes

Tatar 韃靼.

良: good, virtuous, respectable 人: man, people, mankind 良人: husband 罢: cease, finish, stop, give up

远: distant, remote, far, profound 征: conquer, invade, attack

远征: an expedition, esp. military, march to remote regions

View the following images related to the poem, famous spots around Chang'an and others:

1. Yumen Pass, Yang Pass, and the Great Wall (light brown lines) in Tang Tynasty:

About Yumenguan/Yumen

Pass/Jade Gate 玉门关 and Yangguan/Yang Pass/Yang Gate 阳关:

Jade Gate is located at the westernmost extension of the northern part of Great Wall, about 50 miles/81 km northwest of Dunhuang, Gansu Province 敦煌, 甘肃省. Not far to the southwest is Yangguan 阳关, the terminus of another extension of the southern section of the Great Wall. Both were important military posts; each guarded huge, nearby arsenal warehouses and water resources. They also served as points for carrying out customs controls, collecting taxes, controlling immigrants and emigrants and regulating the movement of merchants in and out of China.

In ancient times, the Silk Road meandered through these passes stretching onward to connect Central Asia with Europe. Before the advent of the silk trade, however, there was heavy trading in jade and other precious stones, which gave the Jade Gate its name. The remains of the two gate complexes are about 42 miles/68 km apart.

View the remains of Yumenguan/Yumen

Pass/Jade Gate

thru Google,

Yahoo

or

Baidu.

View the remains of Yangguan/Yang Pass/Yang Gate

thru Google,

Yahoo

or

Baidu.

2. The Great Wall 万里长城:

Construction of the Great Wall started as early as the 7th century BC, with on and off building activity stretching over hundreds of years. Qin Shi Huang 秦始皇 (the first emperor of a unified China) connected the various fragments and extended the wall

around the 3rd century BC. It was used as barricade against the raids and invasions of the various nomadic tribes inhabiting frontier areas skirting the empire -- from its northeast all the way to its northwest. The signal towers on top of the mountain ranges served as perfect and quick relays to pass emergency military messages to Chang'an. The majority of the existing wall was built or rebuilt, however, during the Ming Dynasty (1368 - 1644 AD).

View the images

thru Google,

Yahoo

or

Baidu.

3. Video about the Great Wall:

The wall was built along the ridge lines and stretched for thousands of miles. As of today, the total length, including all branches, is about 13,000 mi/21,000 km, almost half the length of the Earth's circumference!

View it through -

www.youtube.com/watch?v=BpEWKBB6lYw

(5 mins:34 seconds; filmed by dornes).

It is a stunning view. When imagining the vast labor required to create it, the multitudes of soldiers dispatched to guard it, and the countless souls who perished for it, the eyes of the sons and daughters of China fill with tears.

If you are having problems viewing it thru Youtube (more than likely a geographical restriction protocol at work, as has occurred with some other links), you may try this one thru

www.bilibili.com/video/av40029909

or

sv.baidu.com/videoui/page/videoland?... or

any of the videos thru www.google.com.hk.

How the Great Wall was structured -

view from

www.youtube.com/watch?v=JlFDnOs8lB0

(23:24),

www.youtube.com/watch?v=ne0OagUqhWs (3:26)

or

History of the Great Wall of China (Wikipedia).

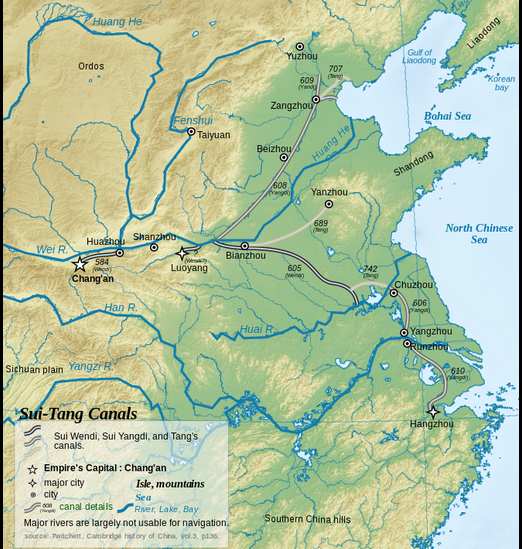

4. Chang'an 长安 -- present-day Xi'an 西安:

Chang'an was chosen as the capital by ten different dynasties, and was, therefore, a very cultural city. Chang'an was also a Silk Road hub during the Sui and Tang dynasties. Scenic sites around present-day Xi'an:

View thru Google or

Baidu.

5. The Mausoleum of the First Qin emperor - Emperor Qin Shihuang:

View thru Google,

Yahoo

or

Baidu.

The Mausoleum was built during Qin Shihuang's reign (247 - 220 BC) and was concealed and went unnoticed for more than 2,000 years, until 1974, when it was accidentally discovered by local farmers digging out a well in a suburban area of Xi'an/Chang'an.

For details about the Mausoleum of the First Qin Emperor:

Wikipedia.

6. The Huaqing Palace 华清宫, located at the northern foot of Mt. Li 骊山, was a scenic vacation resort for the Tang royal family. Bai Juyi's poem,

"A Regret Forever" "长恨歌", describes consort Yang Guefei enjoying the indoor hot spring at the Palace's Huaqing Pool 华清池, and brought fame to the area. View Huaqing Palace environs

thru Google

or

Baidu.

7. The oldest mosques in Chang'an

The Western Great Mosque of Xi'an 清真西大寺 built in 705 - Baidu

or

Google and

Eastern Great Mosque of Xi'an' 清真東大寺 built in 742 - Baidu

or

Google.

8. View traditional Chinese Muslim food in Xi'an

thru Google

or

Baidu.

There are many Muslims living in Xi'an today. During the Sui and Tang Dynasties, many Muslim merchants came to Chang'an to engage in trade and business and later decided to stay in China permanently. During the An Lushan Rebellion, thousands of Islamic mercenaries were also dispatched to China to assist the Tang against An Lushan. Some of them chose to settle in China after the war.

9. Chang'an/Xi'an cuisine:

thru Google,

Yahoo

or

Baidu.

View Xi'an

Jiaozi 餃子 (Chinese dumplings) thru Baidu.

10. Chinese calligraphy 子夜吴歌书法:

View thru Google or

Baidu.

About Li Bai's Life Journey in Details

(1).

Li Bai's Birth and Childhood

Li Bai (701 - 762; lived mostly in the High Tang period and only a few years into the beginning of Mid Tang period), the most famous romantic poet in Chinese history, penned numerous masterpieces that are still memorized and chanted by Chinese of all ages today. He went by many names; his most popular and well-known title being Shi Xian 诗仙 - "the Poet Immortal" or "the Poet Transcendent”. His name has also been romanticized as Li Po or Li Bo. Thirty-four of Li Bai's poems are included

in the popular anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems,"

second only to Du Fu's thirty-nine poems.

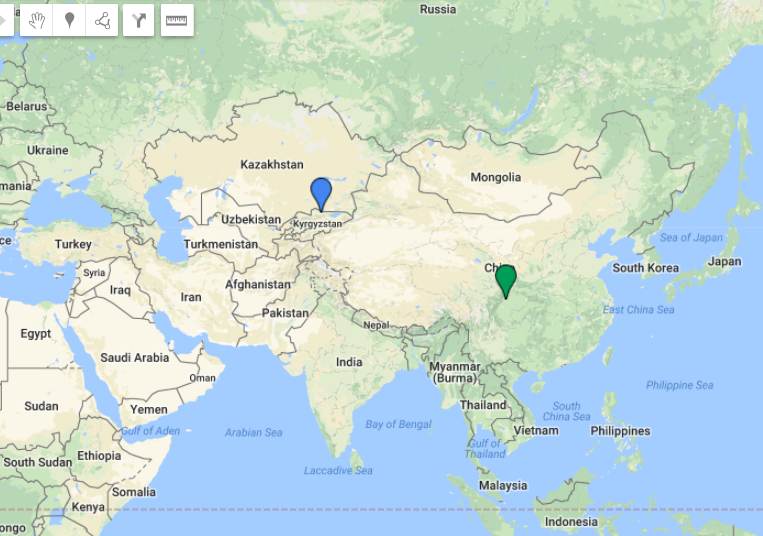

Li Bai's ancestors were from Longxi, Chengji

陇西, 成纪, in present-day northern Qinan county, Gansu Province 秦安县北, 甘肃省. They were banished to Tiaozhi 条枝 in the Western Regions 西域, today's Central Asia, during the Sui Dynasty by the Sui ruler.

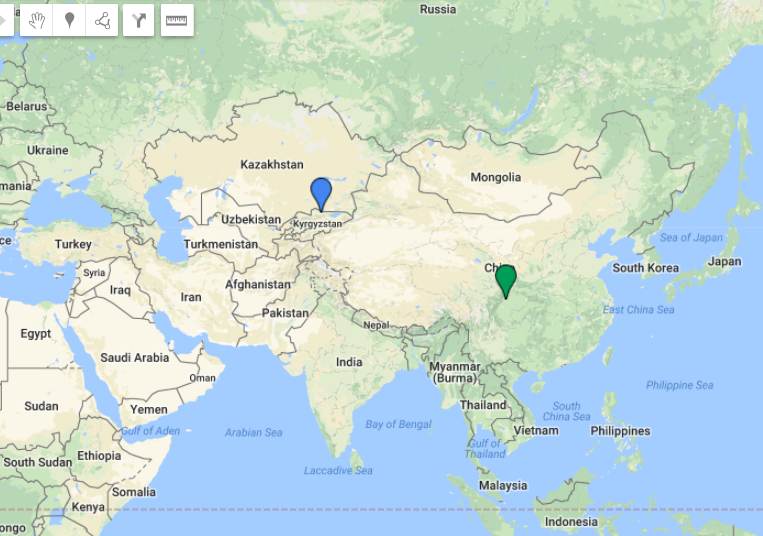

As for Li Bai's birth place, according to Guo Moruo 郭沫若, a historian and ancient writing scholar, Li Bai's ancestors moved from Tiaozhi to a prosperous silk trading city Suiye 碎叶, also in Central Asia, within the Ansi Protectorate 安西都护府, and Li Bai was born over there. Suiye was

also known as Suyab, once a flourishing trading city on the Silk Road and now an archaeological

site in modern day Ak-Beshim, Kyrgyzstan.

View present-day Ak-Beshim (Suiye) in

Kyrgyzstan

thru Google or

Yahoo.

View details regarding

Ak-Beshim:

Wikipedia.

Li Bai's father, Li Ke 李客, was probably a very successful merchant, since the family was installed in one of the thriving commercial centers of the empire. In 705, Li's father moved the family back to China and settled down in Jiangyou, Sichuan Province 江油, 四川省. (

View Jiangyou thru Google or

Baidu.)

(Jiangyou is bordered on the northeast side by Mianyang City 绵阳市 - today's "Silicon Valley" in China.)

Speculated birthplace of Li Bai- Suiye (the blue drop shape) and his second "hometown" (the green drop shape):

|

(Source:

Google map -

click here to expand, then click the dots to view context)

The young Li Bai read extensively, devouring not just Confucian classics, but

also various tracts on astrological and metaphysical subjects, including the Chinese classic text -

Tao Te Jing/Dao De Jing 道德经 (Wikipedia).

He was also skilled in swordsmanship.

His place of birth, his tall girth, and his angular

facial features, suggested that he was possibly of mixed race. It was said that he was conversant in at least one foreign language due to his background and upbringing.

In 725 at age 24, Li Bai left his second hometown, Jianyou, to explore the world. Being young, ambitious,

and without

financial constraint, he embarked on a knight-errant-like journey. Heading east down the Yangtze River, he explored all the most popular cities and interesting spots along the Yangtze River including

the Three Gorges, the largest lake Dongting Lake 洞庭湖, the famous Mount Lu 庐山,

all the way to Jingling 金陵 (present-day Nanjing 南京, in Jiangsu 江苏 Province).

While passing through the Jingmen Gorge, he left behind a beautiful poem "Bid Farewell at Jingmen" 荆门送别.

Along the way he met and befriended various poets and social elites, including Meng Haoran, who Li Bai had long admired.

Li Bai wrote several poems in admiration and praise of Meng, including the very popular one - Seeing Meng Haoran off at Yellow Crane Tower 黄鹤楼送孟浩然之广陵 (included in the book - poem #02).

While touring Hubei, Li Bai was introduced by friends to the family of the former Prime Minister Xu Yushi 许圉师.

Li, at age 26, was young, handsome, and well-built. He excelled at both swordsmanship and literature, and had about him a chivalrous and gentlemanly demeanor. A budding poet, he was well-received by Xu's family and eventually married the former Prime Minister's granddaughter, Xu Ziyan

许紫烟. The couple settled down at Peach-flower Rock, near Li's in-laws in present-day

Anlu, Hubei Province 安陸, 湖北省.

Although Li Bai would travel from time to time or take short mountain sabbaticals (to enhance study and reflection) for the purposes of obtaining a position in the imperial court, the couple led a content married life with little financial burden, with Xu Ziyian bearing a daughter, Li Pingyang 李平阳, and a son, Li Boqin 李伯禽.

While away from home,

Li Bai wrote many letters and poems to his wife

to express his loneliness and longings, some of which were very witty and humorous.

The blessed marriage lasted for 12 years. In 740, Xu Ziyian passed away. Since several of Li's close relatives lived in Renchen

任城, located on the south side of present-day Jiling city, Shandong Province 济宁市, 山東省, Li Bai moved his family there. This was not far from Lu county, where Confucius' hometown is located.

After settling down at Renchen, Li Bai managed to spend some time living in seclusion with five other hermits on Mt. Culai

徂徕山 (

view Mt. Culai thru Google or

Baidu).

They settled by a scenic brook in a bamboo forest, and hence the six of them earned a collective name - "The Six Hermits of Leisure of the Bamboo Brook" 竹溪六逸. Needless to say, Li Bai spiritually enjoyed his time there, taking in the surrounding mountain scenery, drinking wine, enjoying tea, playing music, practicing his fencing, and especially chanting poems together with his like-minded companions. While living on Culai Mountain, Li Bai continued to maintain contact with the local intelligentsia and gentry through letters and visits in order to get his name heard. This was the fashion during Tang Dynasty for ambitious scholars to obtain a central government appointment in the imperial court. Li Bai lived on Culai Mountain intermittently on three separate occasions.

Mt. Culai, the sister mountain of Mt. Tai 泰山, lies about 12.5 mi/20 km

to the southeast of Mount Tai. In Chinese feudal tradition, emperors would come to this area atop Mt. Tai and hold Heaven-and-Earth worship ceremonies 祭天祭地, also called fēngchán 封禅, during prosperous periods to pay gratitude to Heaven and Earth. Another main purpose was to justify and reify their "superpower" and authority over their people. After the ceremony, the emperors would also often stop at nearby Qufu 曲阜 in Lu county, the birthplace of Confucius, to hold a ceremony honoring him 祭孔大典.

Early in the Han Dynasty, Emperor Han Wudi 汉武帝 had paid three visits to the area, performing the aforementioned ceremonies. Several Tang emperors did so as well. Emperor Tang Ming Huang performed the ceremonies for the first and only time in 725, the year Li Bai was just stepping out of Sichuan to explore the world. While holding ceremony in Lu county, Tang Ming Huang composed a poem called "Passing through Zou Lu and offering a sacrifice to Confucius with a sigh" "经邹鲁祭孔子而叹之". This is the only poem by the emperor, himself, that is included in the anthology "Three Hundred Tang Poems".

Living on nearby Culai Mountain and cultivating a reputation as a learned, self-sufficient, capable man, Li Bai provided himself the chance of being recognized and introduced to the Tang emperor during these ceremonies and would have had the opportunity to be possibly "fast track" into the imperial service.

Before his wife passed away, Li had lived in seclusion on several other mountains as well. One of these was

Zhongnan Mountain 終南山 (

view the mountain, hermits and monks thru Google or

Baidu,)

about 10 miles south of the Tang capital of Chang'an. He lived there around age 29 for less than a year. During the early Tang, the famous scholar hermit Lu Cangyong 卢藏用 lived on this same mountain and was called in by

Empress Wu Zetian 武则天

to work for the central government. Lu began at the position of a remonstrative official - Zuoshiyi 左拾遗 (

duties of remonstrative officials in the Tang Dynasty

and

rank schedule of the imperial civil service system), working his way up quickly to the Shangshu-Youcheng 尚书右丞 level, i.e., almost to

the position of prime minister. This is the origin of the Chinese idiom "Zhongnan Fast Track" "终南捷径". Li Bai, however, did not meet with such fortune on Zhongnan Mountain.

In 742, Hè Zhizhang 賀知章, about 83 years old at the time and a leading light of literature and high-level imperial official, read Li's poems, marveled at his literary talent, and praised Li Bai as the "Transcendent Dismissed from Heaven" or

"Immortal Exiled from Heaven"

"謫仙人". From this point forward the acclamation "Li Bai, the 'Transcendent Dismissed from Heaven' " began to spread throughout the empire. And the two cemented the bond of a lifelong friendship.

(2). Li Bai's Ambitious Dream Starts to Bud - An Audience with the Tang Emperor

In the late summer of the same year, Emperor Tang Ming Huang, who had caught wind of Li Bai's reputation, summoned him to the the capital Chang'an for an audience. From Li Bai's home to Chang'an was nearly a distance of 600 mi/965 km, as the crow flies. Li did not arrive until the autumn.

Emperor Tang Ming Huang, an expert on military strategy who also excelled at literature, greeted Li Bai at the Grand Palace in person. During the banquet, Li's personality, wit, and political views fascinated Tang Ming Huang. The emperor even personally seasoned the soup for Li Bai.

The next year, Li Bai was assigned a

Hanlin 翰林

position at the Hanlin Academy

翰林学院 within the imperial court and appointed the state Grand Secretary.

As a result of the emperor's favor, Li was never required to take the imperial examination to attain the title of jinshi, a usual prerequisite for selection and assignment to a Hanlin position. Indeed, Li Bai never attempted to take the

imperial examination at all.

It was rumored that this was because his ancestors had been banished to Central Asia for some kind of crime. The norm at the time was that offspring of criminals were automatically disqualified from taking the exam, but his ancestors were banished in the Sui Dynasty (581 - 618)

and the Sui was overthrown by the Tang in 618, some 80 years before Li Bai was born!

Being from a merchant family also would have disqualified him from taking the imperial examination, though. This policy was adopted most likely to prevent collusion between government employees and businessmen. But in reality, this policy was never consistently implemented. Highly wealthy merchants could always circumvent the rules and secure important government positions. One such example was Wu Shiyue 武士彠, a successful lumber businessman with good connections to the Tang royal family, who secured several important government positions early during the dynasty and indirectly helped his daughter -

Wu Zetian 武则天

“usurp” the throne. (There is an entire chapter devoted to Wu Zetian -- another Tang poetry promoter and grandmother of Tang Ming Huang -- in "Tang Poems" volume 2.)

This regulation was eventually repealed by the following Song (Sung) Dynasty 宋朝, and almost all classes of males (and only males) were thereafter permitted to take the exam. In any event, during Li Bai's lifetime he often broke from convention and followed his own path.

In the beginning, Li led a fairly pleasant life at court. The famous verse "Guifei grinding ink, Lishi pulling off boots" "贵妃磨墨, 力士脱靴" describes this period. It depicts Yang Guifei 楊貴妃, Tang Ming Huang's most adored consort, grinding Chinese black inksticks into ink for Li to pen down a poem, while Gao Lishi 高力士, Tang Ming Huang's favorite

eunuch 宦官,

(and the most politically powerful figure in the palace), assists in pulling off Li's snow stained boots under Tang Ming Huang's request. All to facilitate Li’s comfort and creative genius. It was also suggested that whenever Li Bai published a new poem, there would be a run on paper in Chang'an, sending the price soaring, with everyone rushing out to obtain copies of his new work.

Li's main duty was to handle secretarial works and record tasks for Tang Ming Huang, which included accompanying Tang Ming Huang to important ceremonies and festivities and documenting them. Tang Ming Huang probably intended that through Li's exquisite writing, the records of his reign would be of particular interest to future historians and scholars.

A secondary duty assigned to Li was composing poetry for the emperor. This resulted in the poem,

Qingping Song (1) 清平调词之一 (included in the book - poem #03)

which is a flattering and fawning piece about Yang Guifei and reflects the desires of Tang Ming Huang.

After working for nearly two years at the imperial court,

the incompatibility of Li's personality with court life began to take its toll, as Li was never one

to be bound or driven by secular rules.

Detesting the political machinations, Li doubted if it was in his best interest to remain at the court.

During this period, the treacherous Prime Minister Li Linfu 李林甫 held tremendous political power, running the country by himself and pushing aside all other capable individuals and potential rivals. All the while, Tang Ming Huang spent most of his time and energy indulging in a lascivious lifestyle with Consort Yang Guefei.

More importantly, it was rumored that the

eunuch

Gao Lishi had always felt that being forced to pull off Li Bai's boots was exceedingly humiliating. So he started to badmouth Li Bai to Yang Guifei. He asserted that it was inappropriate for Li Bai to have compared her beauty to that of consort Zhao Yanfei in his second poem "Qing Ping Ballad #2". Zhao was originally of very low birth and status. She was a consort of Emperor Han Chengdi during the Han Dynasty, and was famous for her beauty and slender waist; in contrast, Yang's

great-great-grandfather had been a key official during the previous Sui dynasty, and she had a plump figure, which was the fashion of the Tang Dynasty. Both were consorts doted on by the emperors of their times.

Gao Lishi had been given command of the imperial military forces and had defeated several adversaries in the power struggle for Tang Ming Huang to win the kingdom back for Tang Ming Huang's father. Having established meritorious achievements, he was conferred with the rank of Biaoqi Great General 骠骑大将军 (4th level in military service systems) by Tang Ming Huang, thus holding substantial imperial court military power in addition to political power. He was the favorite eunuch of Tang Ming Huang and even the powerful Prime Minister Li Linfu sometimes publicly flattered him. With such a cast of powerful officials potentially arrayed against him, Li Bai saw the writing on the wall.

(3). Li Bai Quits and Leaves the Powerful Center of the World - the Imperial Court in Chang'an - Forever

In traditional Chinese culture, the most glorious purpose in life was to pursue meritorious honor and fame 功名 (pinyin: gōng míng) in the imperial bureaucratic system. To be able to gain societal recognition in making one's mark on the people and the country was considered of the highest honor. Yet the quality and nature of being a great imperial statesman are quite different from that of being a successful poet, especially a romantic poet. Li finally had an epiphany and abandoned the traditionally defined path to success. Like a fabulous bird, he required an expansive space to fly and soar and not be bound in a golden cage. Hence, his poems began to reflect his desire to leave his bureaucratic mission.

Recognizing that Li Bai was unwilling to continue serving in the court, Tang Ming Huang released him with a handsome severance in the spring of 744.

After a series of farewell parties, Li Bai wrote a moving poem "The Difficult Journey" "难行之旅" expressing his life's ambitions, difficulties he had encountered, and his outlook for the future. And then he said goodbye to the royal court - the center of world power and influence that he had once obsessed about.

(4). The Two Greatest Poets Meet for the First Time

Li Bai was characteristically always an optimist;

no setbacks ever seemed to frustrate him, and he could always find a way to see the bright side of life.

Leaving Chang'an and the setting sun behind him in a relaxed and light mood on his

way home, he traveled to and toured Luoyang 洛阳, which was once the capital during

Empress Wu Zetian's